Ashley Walters on ‘Top Boy’ season four, turning forty and lasting TV success

As the new season of Top Boy begins, Rolling Stone UK meets lead actor and rapper Ashley Walters to talk So Solid Crew, turning 40, and the responsibility that comes with being in a position of power in the British TV industry

Being an actor is not something Ashley Walters has always been upfront about. Although he attended Sylvia Young Theatre School and made his TV debut portraying Andy Phillips in Grange Hill in 1997, many of his peers had no idea he acted at all.

Under the alias Asher D, Walters had risen to prominence as a rapper in the hip hop and UK garage collective So Solid Crew. Then, one afternoon, So Solid Crew were preparing to perform for Radio 1 Live Lounge at Abbey Road Studios. “We all sat in a green room and were eating lunch and there was a TV in there,” Walters begins. “Someone turned the TV on, and everyone was minding their business, talking, until I popped up on the screen. It was a character I played called Omar in The Young Indiana Jones Chronicles, which used to be on Sky One back in the day. It was me. Riding on this camel. And everyone’s kind of like: ‘Oh, shit, Ash, is that you?’ and that’s how everyone was introduced to the fact I was an actor as well.”

The rapper-actor formula is something that is now revered, but Walters claims this was not always the case. “Believe it or not, it was slightly frowned upon back then to be an actor. I didn’t get a lot of positive responses from my peers. If you wanted to be an actor, it was like, ‘Why would you do that? Just be a musician.’”

When I meet Walters in an east London studio, we reflect on being weeks away from the premiere of the second season of the rebooted Top Boy franchise. The crime drama series has nurtured the acting talents of UK rappers including Dave, Scorcher, Little Simz, NoLay and Kano. Walters believes that the ability for these artists to flourish on screen is because Top Boy is the kind of social realist drama speaking to Black life that wasn’t available for him when he was younger.

“We didn’t have a genre back then that represented Black people in the way that they’re represented now,” he says, “so most of the parts you [would] play didn’t really ring true, or relate to a Black audience. There weren’t things like Top Boy back then. There weren’t things that were authentic. Stories that are written by ourselves and for ourselves, that didn’t exist.”

Now Top Boy is celebrated for its fusion of UK rap talent with drama. Its 2019 soundtrack, A Selection of Music Inspired by the Series, saw the contributions of British artists including AJ Tracey, Fredo, Ghetts, and Nafe Smallz. But according to Walters, the series was not imagined as a medium through which UK rap could flourish: “It wasn’t on purpose; we didn’t set out to make this a show to bring musicians into and they flourish as actors or whatever.” This has just been a brilliant byproduct of its success.

Walters, who turns 40 in June this year, is nearly three decades deep into the entertainment industry, and his professional trajectory has seen him transition from being marked for his precociousness (joining at 17, he was the youngest member of So Solid Crew), to becoming a senior industry figure. There’s a confidence and charm he has that only comes with age and maturity; and the ability to let go and unclench.

“There weren’t things like Top Boy back then. There weren’t things that were authentic. Stories that are written by ourselves and for ourselves, that didn’t exist”

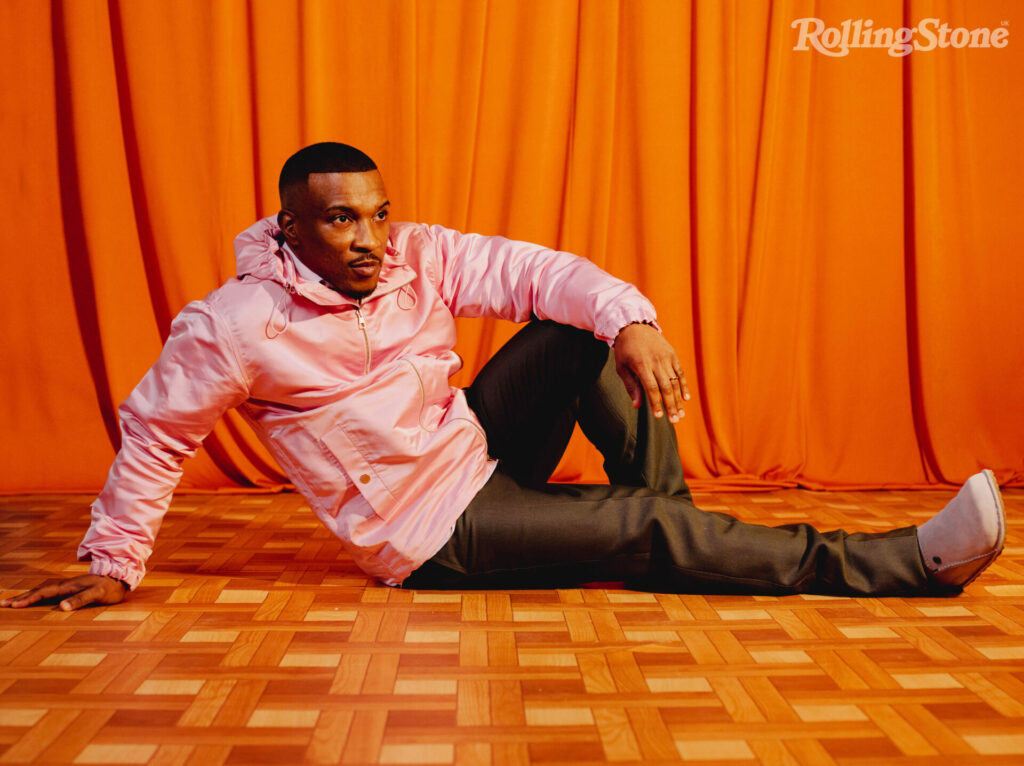

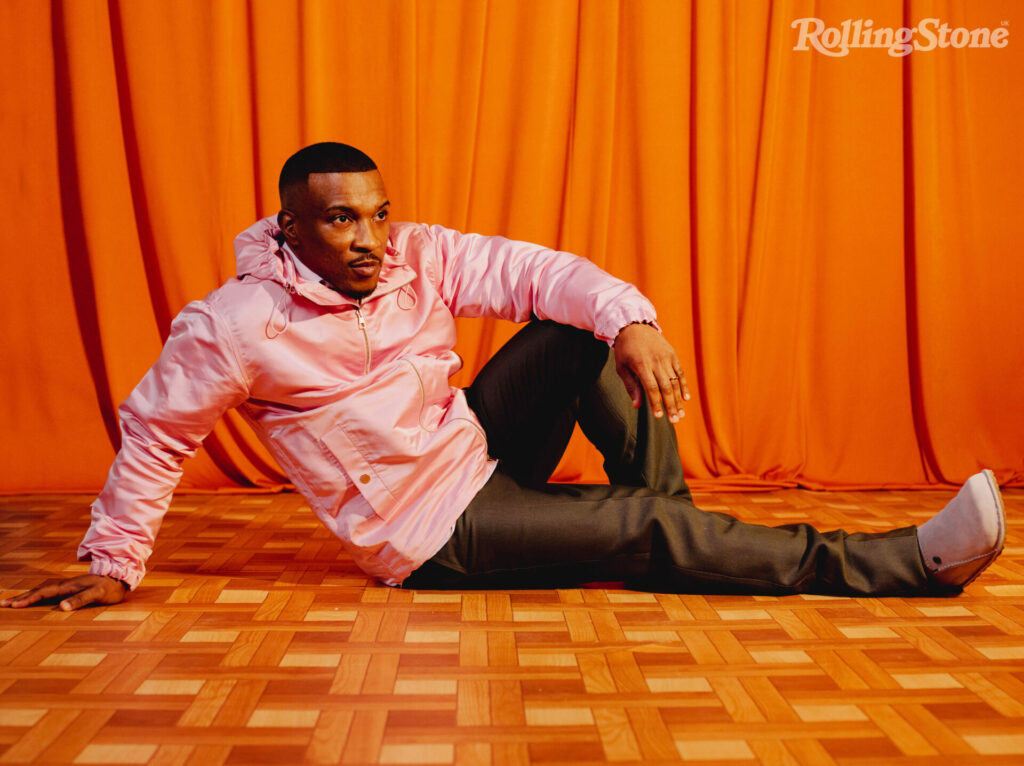

On set for his photoshoot, he’s playful and full of banter. He comes out of the dressing room breaking into sprints and boxing swings as he hypes himself up for the day. He’s asked to pose with a pair of sugarbush Protea flowers and swings them around like nunchucks. He’s singing along to Notorious B.I.G.’s ‘Juicy’ and Wu-Tang Clan’s ‘Gravel Pit’, but he also asks where the newer tunes are at. I ask if he was offended by the throwbacks. “I weren’t offended!” he protests, chuckling, “do you know what it is, it’s a slight insecurity ’cos it’s like, I know I’m getting older, and sometimes you’re like, ‘Did someone put this on for me?’, and every room I go into I’m the eldest these days, and that’s a shift for me.”

Among five top-20 hits, it was the platinum-selling No. 1 ‘21 Seconds’ which saw So Solid Crew’s popularity explode. How did he cope with exposure to fame and success at such a young age? “In hindsight, I’d say it was really difficult to cope with, but at the time it was something I didn’t think about,” he says. “When it came to the success we had, as much as it was slightly overnight, and something we weren’t expecting, I had 30 big brothers to protect me from a lot of the stuff that was really going on.”

Even so, the group undeniably occupied a contentious space in British culture which came with its own pressures. “It came at a time when what was happening domestically in our city [London] was quite prominent in the media — and that was gun crime, knife crime, and that was the focal point… and I guess we became scapegoats for what was wrong with inner-city youths.”

This was certainly the line parroted at the top tiers of government. In 2003, Labour Culture Minister Kim Howells singled out So Solid Crew and the “hateful lyrics of those boasting, macho idiot rappers”, drawing a direct line between their music and gun and drug crimes which had swept the capital.

“Top Boy came at a time when what was happening domestically in London was quite prominent in the media — and that was gun crime, knife crime, and that was the focal point… and I guess we became scapegoats for what was wrong with inner-city youths.”

Howells’s comments were condemned for racism and criminalising Black music culture, with responses emphasising that So Solid Crew’s sounds reflected the concerns and troubles afflicting inner-city Black youth. That, for Walters, is So Solid Crew’s enduring legacy.

“That sort of group, So Solid, had never been seen before in that form,” he explains. “A group of people that spoke truthfully about what they were experiencing, where they came from, and the impact that was having on their community. It made a lot of people stand up. But also made a lot of people fearful of the truth. And I guess we took the brunt of that. We kind of died on the cross.” At the time of the minister’s comments, Walters himself had only months before been released from an 18-month stint in a young offenders institution for possession of a gun. He affirms that it wasn’t plain recklessness or acting macho that led to his incarceration, but something which felt almost inevitable due to the environment he was forced to navigate.

“It’s stupid to say, but I didn’t really expect myself to get into that situation. I thought I was far away from being in that position, but it didn’t take long for me to find myself in that position. It was a wakeup call for me.” His imprisonment steered him in a new direction — rather than acting being a secret shame, a relic of his childhood, it became something he began to pursue with more intent.

“After I was released from prison, the first thing I wanted to do was change my life around, be a different person. The person I was meant to be. And that was hard because it meant turning my back on a lot of people that I had come up with, changing my circle and whatever. It was difficult. And pretty much since I’ve been flying solo.” And in taking this path, he was rewarded with success — taking on iconic roles like Antoine in 50 Cent’s Get Rich or Die Tryin’ in 2005.

Unlike the comradeship Walters found in So Solid Crew, he describes his early acting career as being defined by ruthless competition and a lack of communication between Black male actors. “What it forced on you was a feeling of isolation, and there was a lack of unity. And that’s not because we didn’t want to be unified as people, it was because you knew that there would only be one Black person allowed in this show. You didn’t want your position to be taken from you, so you’re very closed off.”

He claims that as a younger man in the industry, he found it difficult to connect with older Black actors because of this, though he notes that the actor Lennie James was instrumental in developing his career.

The picture is totally different today and he points to the close links actors like Daniel Kaluuya, Damson Idris and Idris Elba, among others, have with each other. For Walters, Top Boy is a production space where these intergenerational contacts between Black British actors can flourish.

“I talk to Micheal Ward a lot”, he says. “We have a really good relationship and he asks a lot of questions: that’s why he’s so good. A smart person always asks.”

The series finale of season one of Top Boy had seen Walters’ character, Dushane Hill, approach Ward’s character, Jamie Tovell, with the offer of freedom from prison in exchange for loyalty and service. Leading up to this, Dushane had returned from Jamaica to run the estate of Summerhouse’s activities, setting him up as rivals against the ruthless London Fields gang run by Jamie. Having offered Jamie a lifeline he’s disarmed him, and thus Dushane is back as east London’s Top Boy.

Despite this, when we meet Dushane again in season two, he’s a gentrifier, building a property empire against the wishes of his mother and finding ways to benefit from the social cleansing of the Summerhouse estate.

“I talk to Micheal Ward a lot. We have a really good relationship and he asks a lot of questions: that’s why he’s so good”

“You look disgusted!” Walters laughs, as I ask him about these details. It will be a difficult direction for fans to swallow, Walters acknowledges, saying of season two that: “What you’re just starting to see is actually Dushane is a cold-hearted person who will do anything to get things his way.”

He says that depicting Dushane in this new series has been personally challenging. “I wouldn’t make the same decisions as him, so you’re always fighting against that. And there is a point where you have to let go and understand that you’re not him.”

Unlike his character, Walters, who grew up on the North Peckham estate, is an opponent of gentrification, having seen loved ones moved out of the Aylesbury estate in Walworth: “It’s something I’ve had to watch in real life with a lot of family and friends that I grew up with, and they end up being shipped out to north England, Birmingham, this place, that place, places they’re not familiar with.”

More empathetically, we can understand Dushane as someone who is attempting to transition out of the unstable, criminal life through more legitimate means — despite how difficult it is to let go of his lifestyle.

“I guess I made it, in the sense that I managed to turn it around. But not everyone does. I guess Top Boy is the story of people that don’t.”

“I’ve got a complete understanding of how trapping that life can be,” Walters says, reflecting on his own past. “If you get into it, and it’s as lucrative for you as it has been for Dushane, I can understand how difficult it would be to walk away from it, just because of the trappings and the money and success it brings. More importantly, the people that you’ve taken on your journey that have also become accustomed to that lifestyle or whatever, are always going to try and bring you back in and involve you in some sort of way.”

Reflecting on his own life and his transition from his youth, he says, “I guess I made it, in the sense that I managed to turn it around. But not everyone does. I guess Top Boy is the story of people that don’t.”

A key difference in filming this season, for Walters, has been that over the past few years he’s been working on production and taken a seat in the directors’ chair. This experience as both director and actor on Top Boy has given him a deeper appreciation for “the pieces of the puzzle, how it’s put together and how you as an actor can be influential in that sense”.

Walters’ training began with his directorial debut Boys for Sky Arts, but this project had first been triggered by him being told to gain experience after he asked to direct episodes of Bulletproof, the action drama he had co-created and costarred in alongside Noel Clarke.

After a Guardian investigation exposed historic and recent sexual assault allegations against Clarke by at least 20 women, Sky cancelled Bulletproof, which at the time had begun production for its fourth series. Walters tells me that he first learned of Clarke’s actions when the nation did. He was at home when he found out the news and the revelations took him by surprise.

“I was upset. It came at a time when we were all just about to start writing and shooting another season [of Bulletproof] that we had just prepared for. But first and foremost it was just shock. It was sadness that this sort of stuff had allegedly been happening as close to me as it did.”

A number of the allegations were connected to Bulletproof, which Walters says was “hard for me to understand. I’m not trying to put myself in the mix, but I was deeply hurt by what I heard and how things went.”

Much like how Walters describes his early experiences in the entertainment industry, he and Clarke had not started out as friends. Their relationship was rocky, “like I was saying before, there wasn’t much unity, we had our own perceptions and reservations about being friends in the beginning”.

When the opportunity arose to work with Clarke on Bulletproof, Walters had relished it: “It was good to be able to develop a show with him and learn from him as well, because he’s been producing, writing, and directing long before I even thought about doing it” — attesting to the seniority and importance of the now disgraced Clarke as an industry figure to generations of Black talent.

Walters reaffirms his support for the women who spoke up against Clarke. “I think it was a powerful thing that they did and I think it’s going to help convince other women to do the same thing if they need to,” he says.

Although he acknowledges that livelihoods were affected by Sky’s cancellation of Bulletproof, he views this as a necessary action (“I think it needed to happen”). Walters doesn’t shy away from admitting that Clarke had been his friend, and I ask him if he has been in touch with him since the allegations broke. “Since this whole thing happened we haven’t been talking,” he says. “We’ve had a few text messages and whatever, but we definitely don’t talk to each other.”

As Walters continues to take on a more senior role in the entertainment industry, he’s thinking about how he can ensure the sets that he works on and the projects he manages are safe environments for those working on them. He’s already had opportunities to put these lessons into practice. Off the back of his directorial debut, Boys, he was offered the chance to direct episodes for the upcoming fifth season of Ackley Bridge. “I’m still in post-production now. It was an amazing experience, but challenging. It’s a challenging thing to direct fast-paced TV.”

He’s also taken to writing shows, one of which is in development with Channel 4, and the other in Sky Studios. He doesn’t give away too many details — but the Channel 4 show he says has been years in the making is called Pirates, “a story seen through the eyes of a 15-year-old kid in 1994, watching the transition from jungle, drum and bass, into garage, through pirate radio”.

It’s not just in his professional life that Walters has been making changes and upgrades. He’s serious about his health: he quit smoking and drinking a year and a half ago; and as his strong build can attest, he works out rigorously. He also stays close to his doctors. “I’m a slight hypochondriac when it comes to my health, my doctors probably get pissed off with me,” he says.

Dietwise, he’s kicking his Deliveroo habit and pays more attention to calories, carbs, and protein — though he admits it’s his biggest struggle. “I don’t sit there happy eating salad all the time; sometimes I want to eat ribs with all the sauces!”

He adds, “I’m just trying to take those incremental steps to make my life last longer, man.”

We then reflect on the fact that Black men, as they age, have to walk with a strong sense of their own mortality — and conversation turns to the recent sudden death of Jamal Edwards, who Walters counted as a friend.

“If there’s one thing we’re learning from recent events, especially with Jamal, who I knew very well, it’s you don’t know when your time is. Your health could be really bad and you don’t even know about it.”

His new home makes it easier to enjoy a healthy lifestyle. In February 2021, a year to the month that we speak, Walters left his home in north London’s Crouch End for the pastoral comforts of Herne Bay, a seaside town on the north coast of Kent. It was the realisation of a lifelong fantasy.

“It’s always been one of my dreams since I was a teen to eventually, when I can afford it, and when the time felt right, to bring up our family outside London.”

Unsurprisingly, Walters’ move, like many others, was largely triggered by London’s extortionate housing market — he has a large family, with eight children. Naturally, he wanted a house with lots of space, so it was “more economical” for him to move away. But a more personal reason driving his desire for a fresh start elsewhere is the intensity of the difficulties he faced in his early life in London. “I didn’t really want my kids to go through the same things I did,” he explains.

So, how is life in Herne Bay? “I don’t know if you’ve ever watched Emmerdale…” he begins. He scans my face, waiting for a reaction and finds none, “…yeah, probably not. But it’s like a village. A really tiny place with a really small number of people that all know each other and are quite traditional; you know, farmers, it has that vibe to it.”

He misses London when it takes him three hours to get to work, but nothing beats the coastline with its fresh air and fun. He enjoys family trips to Broadstairs Beach and Margate and he regularly walks his French bulldog, Max, along the Herne Bay coast. The location complements his love of seafood, too: he’s a regular at Margate’s Buoy and Oyster, and loves the Whitstable area for its large oyster farms.

“It’s a much slower way of life and it’s forced me to be slightly more interactive with my neighbours,” he explains, “I think London, as overpopulated as it seems sometimes, I don’t think people really connect with people that they don’t know, people outside of their network. So I spent how many years living in London and never got to know my neighbours.

“In the year that I’ve been living in Herne Bay, I’ve built really good relationships with the people around me.”

Being able to start a new life in a fresh domestic setting with his younger children is something that’s a source of both real joy and profound guilt for Walters. Thanks to stability, maturity and time, he can be a different kind of father to his younger offspring. “I guess my oldest kids didn’t get the best father in the world, and my youngest kids have got the best father so far,” he says.

In December 2020, he welcomed a granddaughter too, who is very much part of the reset process Walters is experiencing as he approaches 40. “I guess for a lot of grandparents, it’s a nice chance to slightly rewrite history. It’s given me a real opportunity to start again. It’s weird to explain, ’cos the love you have for your grandchild, it’s a different sort of love; it’s slightly more powerful. So yeah, I’m obsessed with my granddaughter, man. I stay in contact with her as much as I can. But then, saying that, I can give her back at the end of the day!” he laughs, throwing himself back into his chair.

Walters’ new lifestyle and philosophy will be reflected in his upcoming music as he continues to resurrect Asher D, a process that began with his 2019 single ‘Top Boy’ featuring D Double E, Big Tobz and P Money. During the pandemic, he created a number of tracks that will be released over the next few years. The first of these, ‘Surgeon’, will drop in March, while an EP, Waters Run Deep, will follow shortly after. “It’s more mellow. I think I’ve gone completely in a new direction when it comes to my music,” Walters explains. “I guess with age I’ve become a bit wiser, and what I’m talking about – my relationship with my wife, kids and peers – reflects where I am today, rather than where I was.”

This interview is taken from the fourth issue of Rolling Stone UK – preorder it here now.