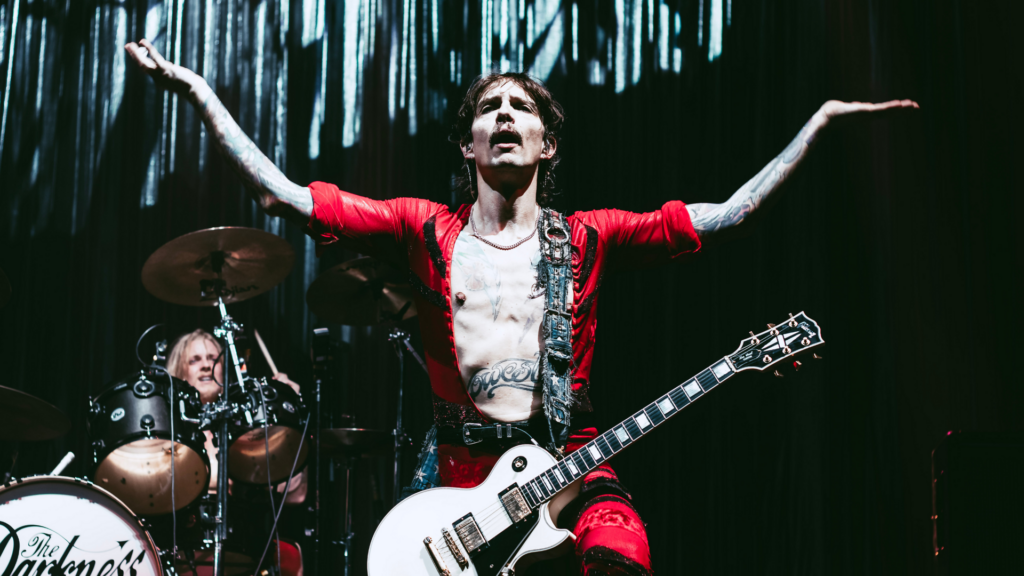

The Darkness’ Justin Hawkins on 20 years of ‘Permission To Land’: ‘I was bulletproof and didn’t give a f**k’

As The Darkness mark 20 years of their debut album, frontman Justin Hawkins looks back on how they briefly became the biggest band in Britain.

By Nick Reilly

When The Darkness first captured the attention of the British public in 2003, they were the most unlikely of outliers in the musical landscape. At a time when fierce pop rivalries were dominating the charts, you wouldn’t bet on a group resembling the aftermath of an explosion at a clothing boutique on the Sunset Strip becoming the biggest band in Britain.

But the group, led by perennially catsuit-clad frontman Justin Hawkins, did exactly that for a brief period. When their debut album Permission To Land arrived in July of that year, the British public immediately fell for a record that unashamedly dealt in face-melting hard rock and choruses that could unite a stadium.

It was the start of a trajectory that would lead them to the top of the music world and, for Hawkins at least, vindication against certain sections of the music press that had previously balked at the group.

“I was bulletproof and I couldn’t give a fuck,” Hawkins recalls to Rolling Stone UK.

“When we got big, journalists from the NME wanted to talk to me after they’d said that we should be killed and replaced with real musicians. I told them to fuck off.”

Within months of releasing Permission To Land in 2003, the group were on that trajectory to super stardom. They won three BRIT Awards in 2004, headlined Reading & Leeds Festival in 2005 and delivered an enduring hit in the soaring ‘I Believe In A Thing Called Love’ – which has rightfully forged its place in the pantheon of great British rock anthems.

While the group followed it with 2005’s One Way Ticket To Hell… And Back, it failed to have the same impact as their chart-topping debut, reaching number 11 in the charts. The group would split less than a year later after Hawkins left the group to enter a rehab clinic for substance abuse, but a reunion in 2011 has given them a sustained second go at it – releasing a further five albums since then.

You can read our whole Q&A with Justin Hawkins about twenty years of Permission To Land below.

It’s been 20 years since Permission To Land, does it feel like twenty years?

In my life that’s three lifetimes! Every seven years I go through some sort of identity crisis, I either fix my teeth or I get a load of tattoos or maybe both.

But everything still feels fresh. It’s very strange because yes there’s the focus on 20 years, but there’s a bit of a spotlight on me because of the performance I did at the Taylor Hawkins memorial show last year, my YouTube and now I suppose I’m obliged to start thinking about a memoir.

All these opportunities are coming in and I just think fuck! I’m old! I never think about it because as I said I have these restarts, but it has been a long time.

It must be nice to go on tour and celebrate such a seminal album though right?

Yes, but the thing that I’m most excited about really is when we go on tour and we get to play those sort of weird songs that aren’t on the main body of the record, you know, the sort of associated tracks and what we used to call B sides in the olden days.

We would record a body of work and it would be like, ok, we try and make everything as great as it can be and the stuff that doesn’t quite sit in with the concept gets used as a B-side. But there’s some genuinely brilliant stuff on there. For me those are really fun songs to play.

Do you worry about getting cancelled or criticised for some of the suggestive lyrics? You’ve got a song on there called ‘Get Your Hands Off My Woman’.

Well, I don’t know if we’d get away with having a naked woman on the front cover for starters. We almost didn’t because we had to do a version for certain American retailers that had a pixelated version of the woman. Back then it was a strange world because you’d go to America and they’d pixelate the woman, but you’d go to Germany and they’d try to make the tits bigger!

I do think the internet has completely homogenised everything, so we know what’s acceptable and what isn’t, so we probably would make a few adjustments.

It is funny though because songs like ‘Get Your Hands Off My Woman’, the approach there is quite toxic and possessive. But the thing is, singing it in such a high register takes a bit of that masculinity away.

It’s also quite tongue-in-cheek too, I think people realised that at the time and I think that is very much still the case.

You’ve spoken before about your frustration that people saw you as a parody and refused to take you seriously…

Yeah, it was frustrating. Especially when people saw us as a tribute to some of the things we’d never listened to. It wasn’t glam rock and that first record has got lots of dirty stuff on it, there’s literally lines about doing heroin. But it’s done with attitude and humour and I do get why people felt that way.

I think it’s because we were so unfashionable that it felt like we were trying to do a trick on people. There was even a weird conspiracy that Simon Cowell had put us together.

The fact is that we’re four individual characters that are so different, apart from the fact that Dan is my brother. I think it was hard for people to understand how this thing actually emerged and that led to a slight suspicion that we were making a big joke at everybody’s expense.

That stuff did kind of stop though when we did support slots for groups like Deep Purple and The Rolling Stones. Proper big established rock groups and we were able to win over their crowds.

Your incredible live presence helped that reputation then?

Yes, because we had nothing that rock purists could use to accuse of cheating. We were really doing it and I think that’s part of the reason why some people have told me we were their gateway band into rock music.

Nowadays you go and see a band and you can’t even hear a fucking amp on stage! If you’re standing side of stage you can only hear drums. There’s nothing exciting about that.

You were, for a period, the biggest band in Britain. Did that feel like vindication against the naysayers?

We used to be really proud of the fact that our audience was made up of people that were of an age where they can remember when the rock and roll aesthetic was a thing that people bought into and, and aspired to and it was proper. And they’re bringing their kids because they’re old enough and the kids are finding out about that kind of world through a band that’s young enough to matter to them.

But as I said., we were something of a gateway drug for rock fans at that point.

It feels like The Darkness are on the cusp of a renaissance once more. You mentioned earlier about the huge success of your podcast and also appearing at the Taylor Hawkins concert, which was incredibly well received.

Taylor was a dear, dear friend of mine and we were both deeply connected with that world. I really prepared for it because it really mattered to me, and it was so lovely to see how well it was received. His godson is our drummer too and he performed as well. It sort of put us back on the radar for a lot of people.

As for the podcast, I just love it because I’m still really into music. I think people think I’m not as dumb as I used to look, so it’s helped with a bit of respect but also, cynically, I can talk about the band too.

The Darkness split up acrimoniously in 2005 and you’ve spoken before about your substance abuse issues. Do you have any regrets about how it ended?

Yeah, but now I get days where I wake up and just think ‘I’m alive’. I didn’t always make great decisions, but I think I had to do a thing where I put my recovery first. In terms of my health that had to be the priority. I lost my friendship group, which was an important thing to have, even if it seems like it’s transient friends that you just misbehave with when you’re doing something like this where you’re in the public eye, it’s so important to have friends that you can speak to for advice.

You’ll lost sight of the right things if you don’t consult people that you trust and with the recovery thing, I cut everybody out. It took me five years to get to a position where I could do things with people who weren’t in the same position as me, and six or seven years to get happy.

Then you have residual shame and all the things you have to deal with, because it’s not easy for everybody to walk away from the triggers that make them behave in certain ways. But the other option is we wouldn’t be sitting here having this conversation.

Did the rockstar lifestyle lead to your addiction issues?

No, it had nothing to do with that. My problems in that area started way before, we’re talking about when I was a teenager. But look, it’s just part of my life and I was just fortunate to be able to have the financial stability after the success to sort myself out.

There’s no rock bands like The Darkness in the UK at the moment. Are you hopeful for a sea change there?

No, it was strange because when we first came up, our biggest hope would have been that we sort of spearheaded some sort of movement to a more uplifting sort of glamorous approach to guitar music.

But it didn’t happen like that really. There was almost a backlash and I think I have seen bands coming through since who take subtle elements of what we did.

Where’s my props y’know? I’d see somebody wearing a cat suit and I’d be like, yeah, you’re not gonna acknowledge that That’s my fucking thing!

But bands like The Struts have come out more recently and said, well, The Darkness is a huge influence to us. I really respect them for that because I think that’s quite a ballsy thing to admit. It’s like, we’re not cool, we never have been cool. We’re rejected!

But that sense of defiance in the face of all that, which you had, seems cool in its own way.

Yeah, maybe. Our first bit of sort of national press that got us a little bit of traction amongst the cool kids was when we were sort of unsigned, not undiscovered because people knew about us in London, you know, we were selling out places like the Astoria and the first unsigned band to do that.

But the audience was made up of like hipsters and the cool kids and it seemed ironic that they liked us.

There was a nameless taste-making magazine that did a huge feature on us and the crux of it was ‘Look at these fucking idiots from Lowestoft! They’re never gonna make it, but we love them! They’re just a small town band who play like it’s a stadium every time they play in a pub, sometimes nobody shows up but they still give it everything.’

We were like, what the fuck? We were so committed to it.

Well exactly. You’d been at it for a good few years before the big time beckoned.

Yeah and that’s why being accused of being a parody so was annoying to me. It was like, if you think we’re a parody, try living in a bedsit for five years doing this fucking music that nobody wants to listen to and tell me it’s a parody because this is my life, you know, and the reason why it worked is because I was living the fucking life and that does mean the drugs, the rock and roll. That’s actually a unfortunate part of the reason why it was successful. If you chipped away at it and accused it of this or the other, what you’d find in the middle is a bleeding heart with rock and roll coming out of every fucking artery.

I felt bulletproof because I couldn’t give a fuck. I couldn’t have cared less. When we got big, journalists from the NME wanted to talk to me after they’d said that we should be killed and replaced with real musicians. I told them to fuck off. I told them to fuck off every single time until we reformed.

There was so many principles at stake that we stood for. Guitar solos, the principles of having fucking loud guitars on stage, the principles of wearing cat suits and doing all that stuff and the principles of not caring what anyone else said did or thought t about us. We just thought fuck everybody, we’re The Darkness.

That’s how it was and maybe that was kind of like one of the things that turned people off after a while, like the histrionics of it. But the whole thing was fuck you, we don’t think we’re cool and we don’t think your opinion is relevant to what we’re doing. So fuck you!