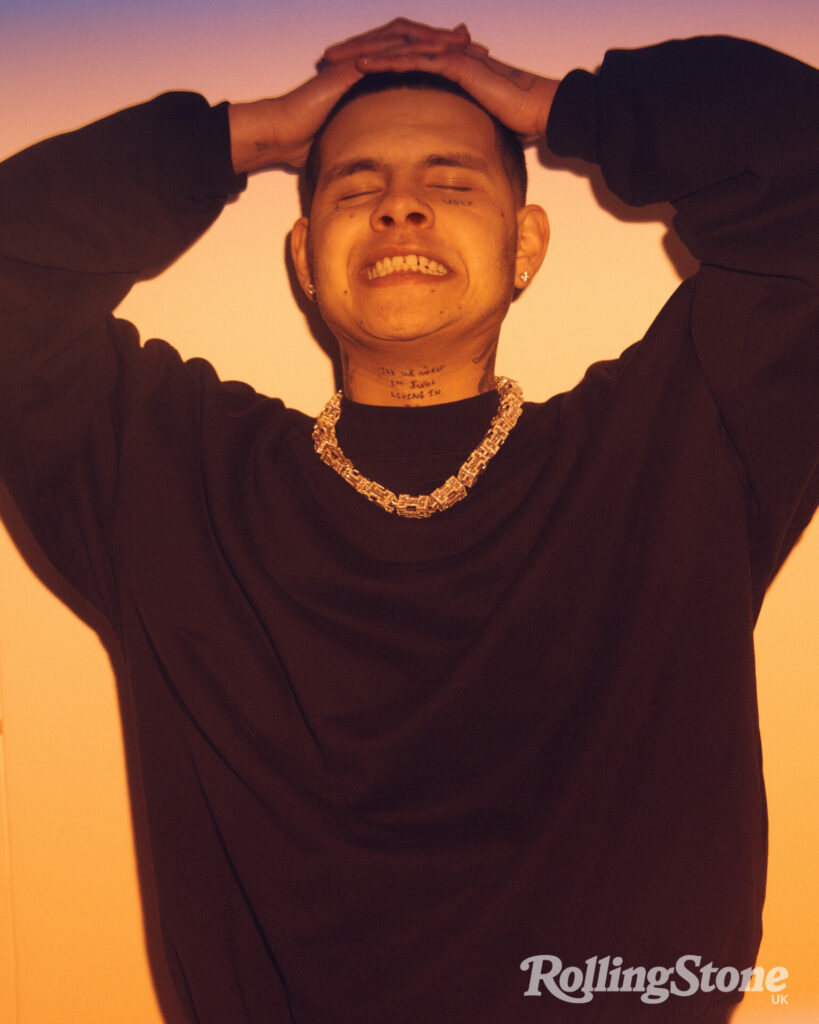

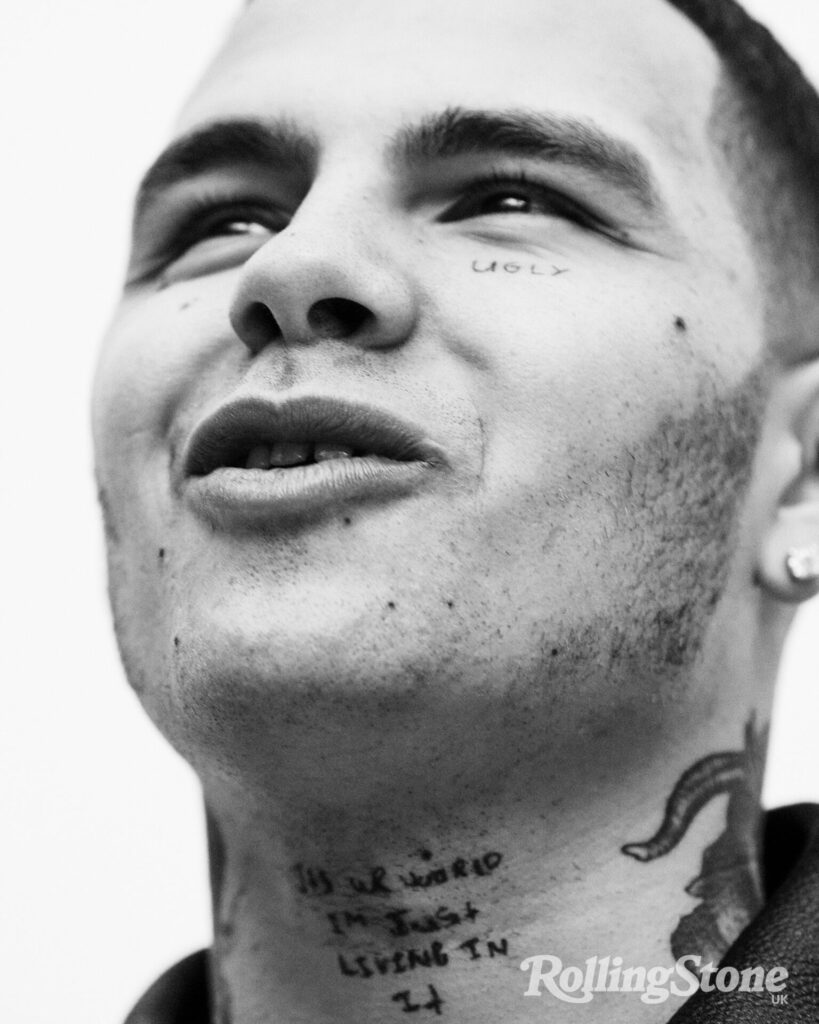

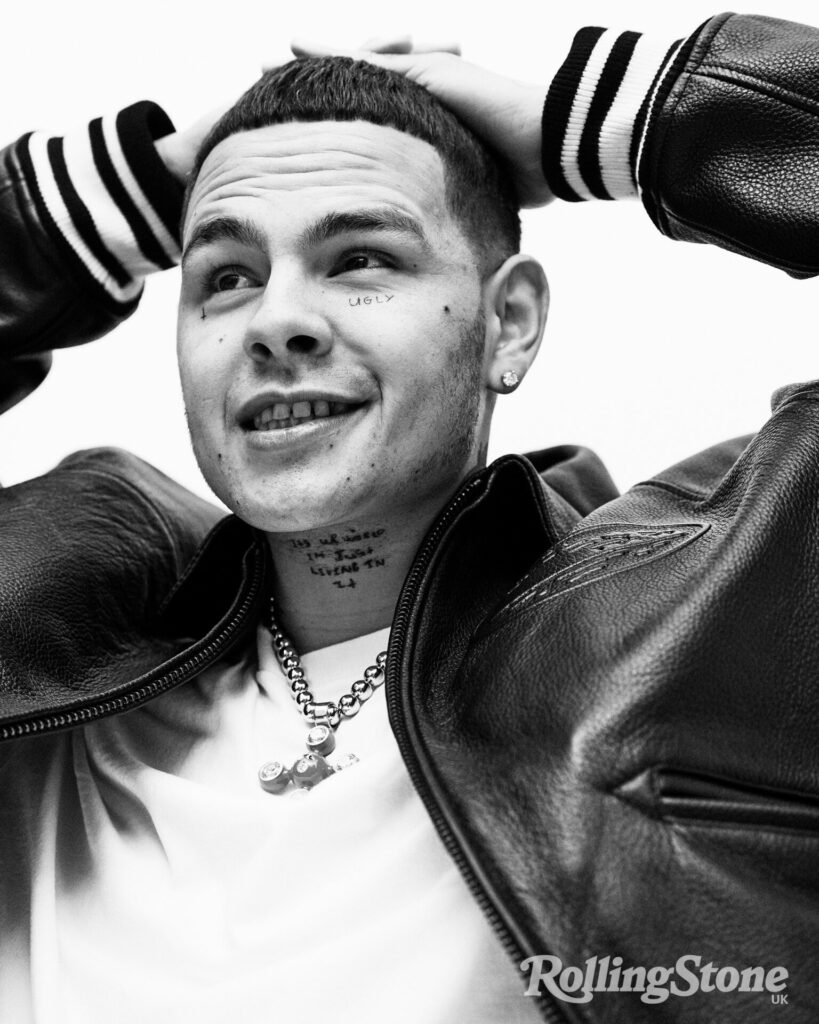

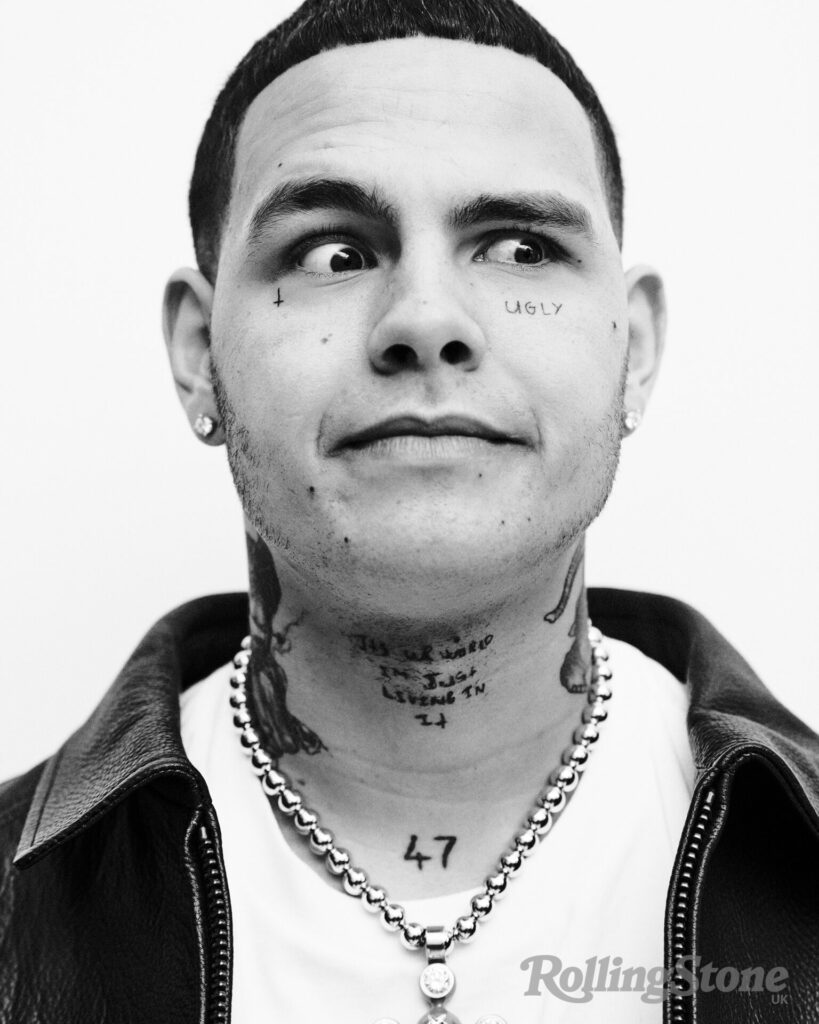

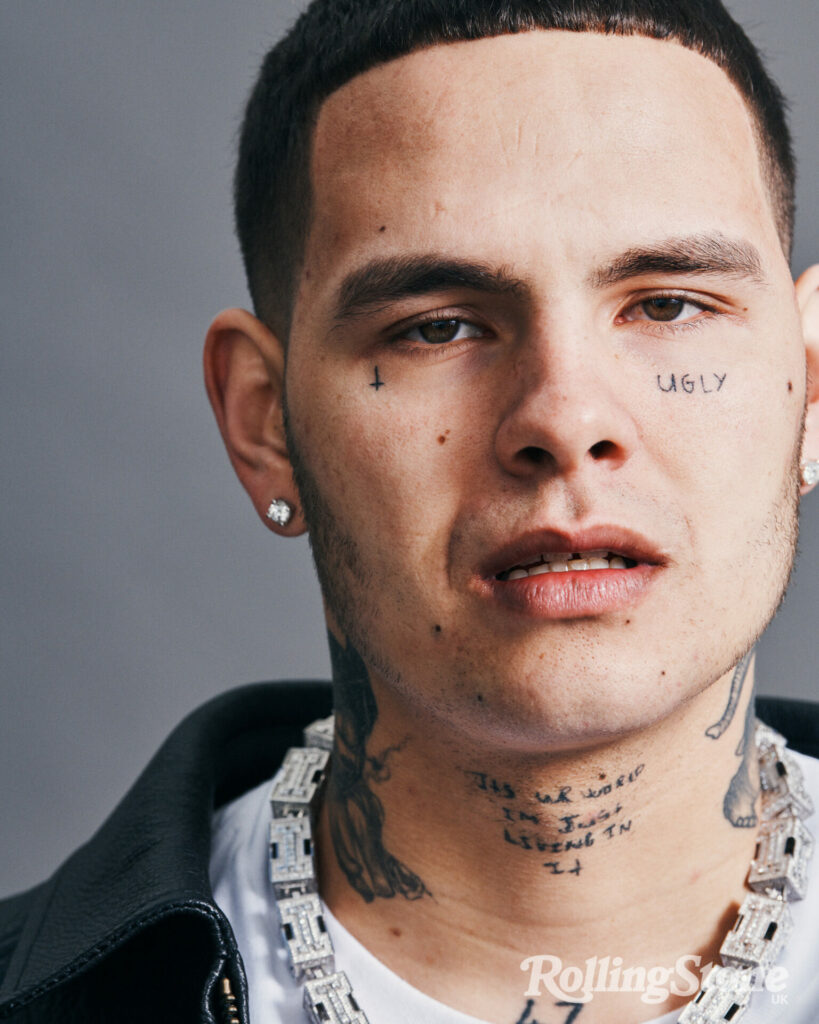

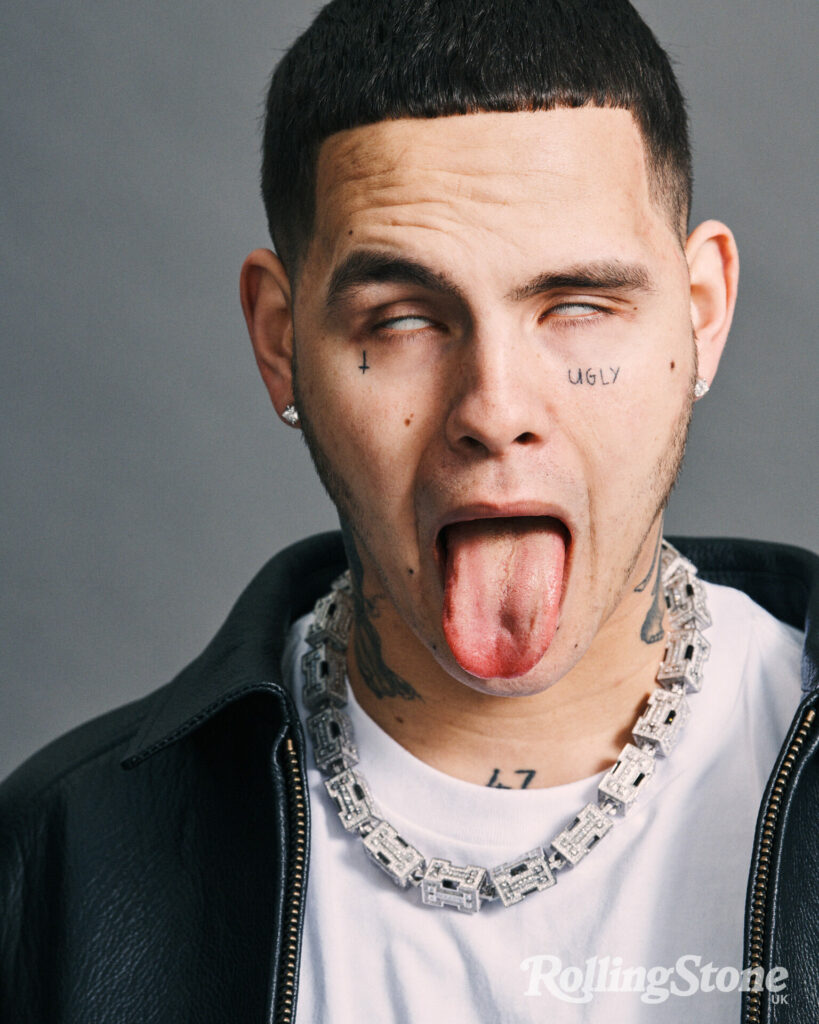

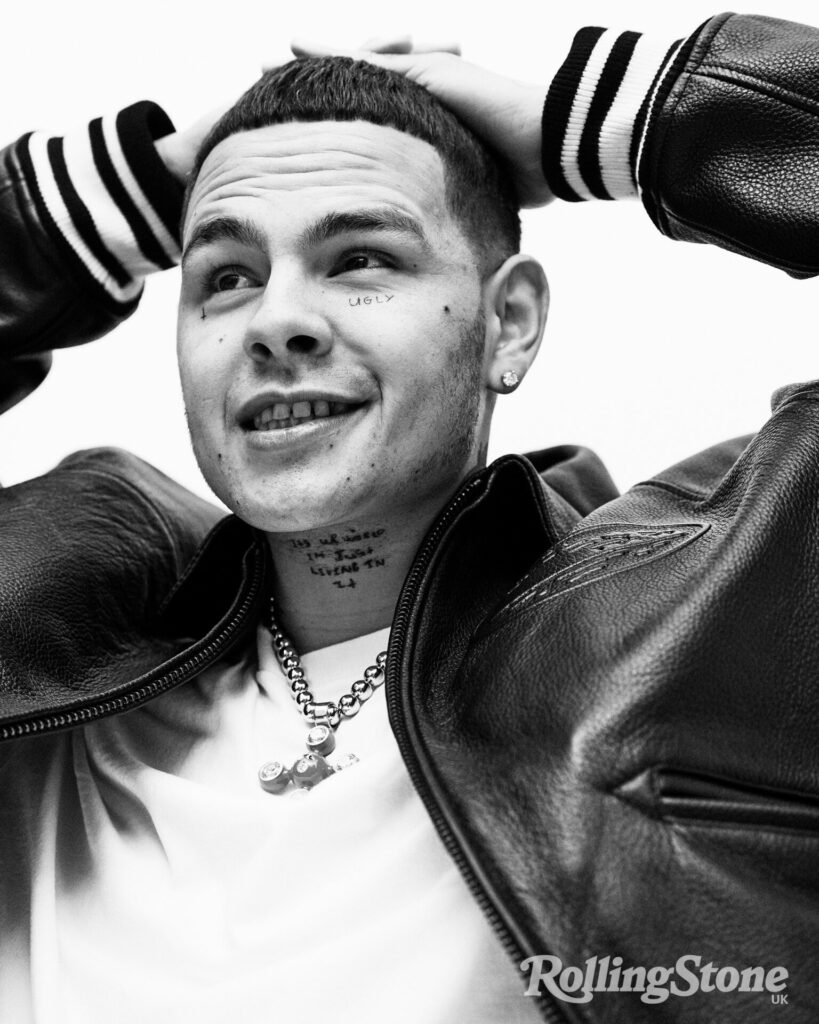

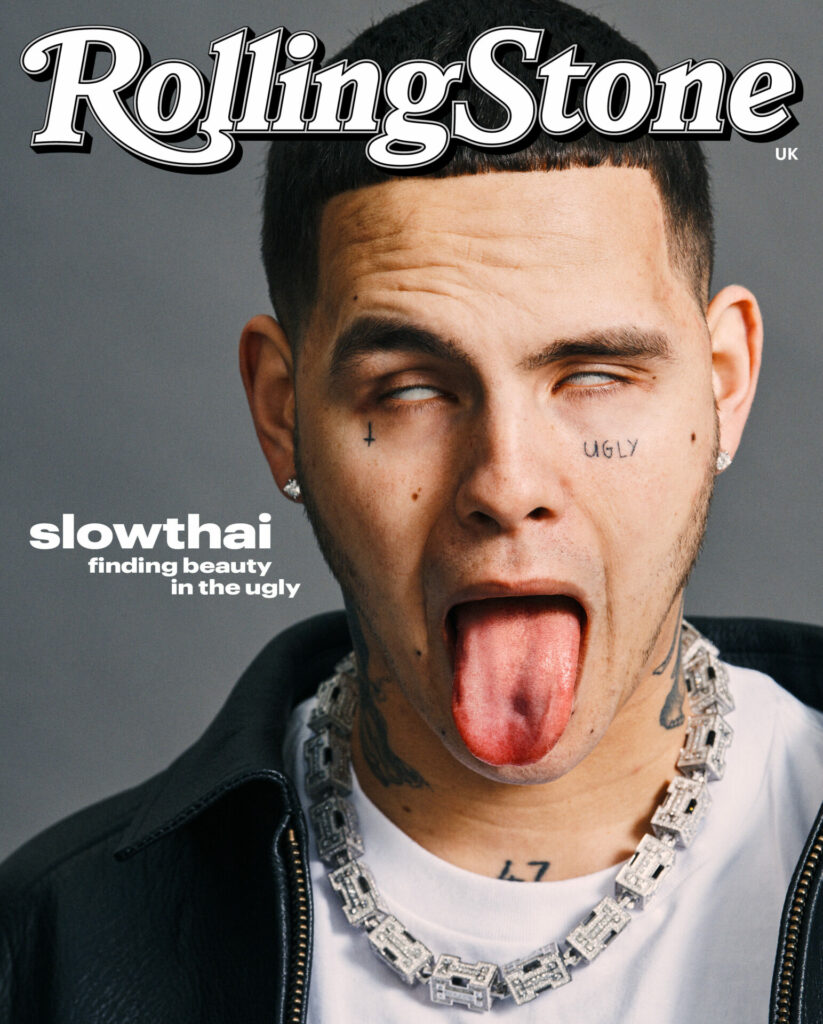

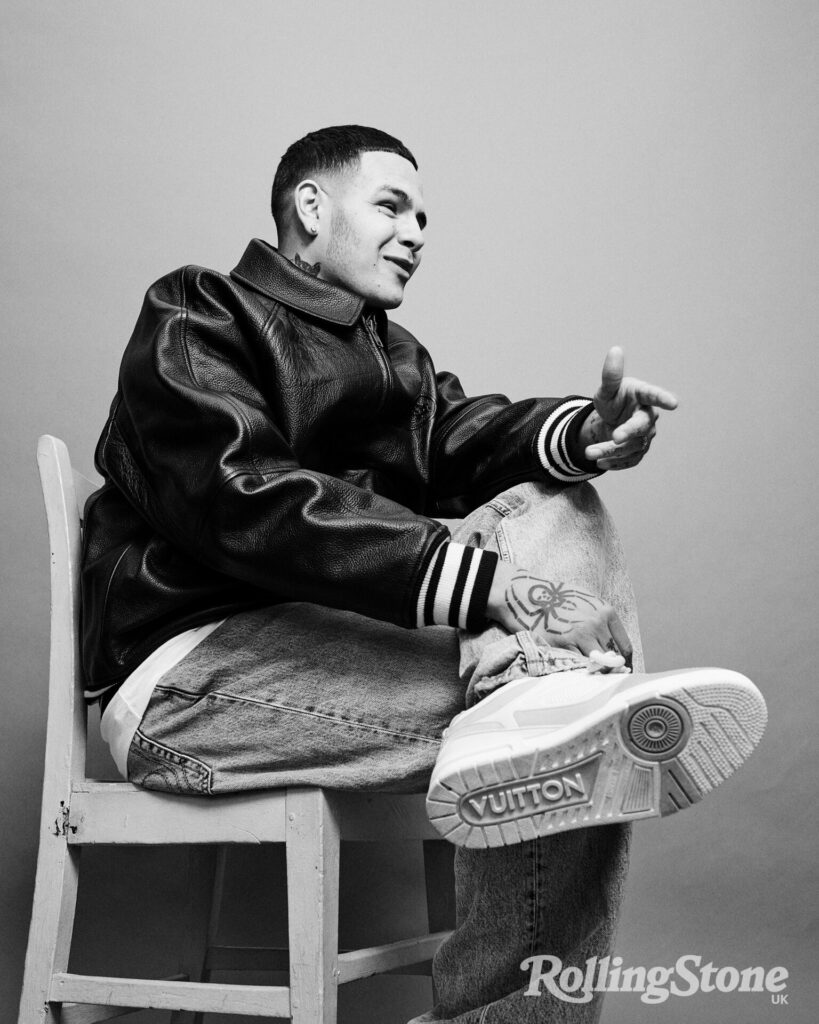

slowthai: finding beauty in the ugly

What do you do when you find out therapy is not for you? If you’re this new dad, you return to your friends and to rock music – the genre Tyron Kaymone Frampton always wanted to make – instead for curative release

By Hannah Ewens

Psychotherapy didn’t work for Tyron Kaymone Frampton. Before you, a therapised reader, get ahead of yourself with preconceptions or misconceptions, he tried. He’d previously dabbled in the great American task of talking about shit with “some guy” and this second time there was plenty to discuss with a professional: he was performing as the rapper slowthai, “burning the candle at both ends” and dealing with the personal pressures of becoming a dad and co-parenting with his son’s mother. But after a few months of committing to the process during his global festival circuit in the summer of 2022, it was game over.

In fairness, therapy: it ain’t for everyone. “I’m not, like, a know-it-all or nothing, but I’ve done my own research, and I give enough people advice from myself to practise what I preach. I could be a therapist,” Frampton says with a smile, sinking into a couch in a private room in London’s Soho. “I might just go study psychology and start doing that.”

The final straw was when he cancelled some sessions and his therapist charged him for them anyway. “I’ve got trust issues”, Frampton says, and what about this “doctor-patient privilege”? He asks if I’ve seen The Sopranos. “Tony Soprano’s fucking therapist goes to another therapist about this don and that therapist probably goes home to his wife and says, ‘Today was a long day, I had this guy who told me…’” Frampton trails off and raises his eyebrows. What’s an Italian-American mobster or a British musician who semi-regularly appears papped and printed in the UK tabloids supposed to do? Risk leaked secrets and more controversy? After everyone’s finally forgotten about the drama at the NME Awards? Nah, mate.

He’s beyond wanting to talk about that night, not to you nor a therapist. That was last album cycle, a trade of necessary evil: repent for doing little more than embarrassing himself publicly and advocate for his new music.

“I didn’t have to answer to anybody. People are always going to hate”

At an industry listening session for his new album UGLY, an hour before we speak, the room is scattered with press and people from streaming platforms. At one point Frampton says, “Is anyone from NME here?” Everyone laughs and yes, someone from NME is here and raises their hand. He wants all the awards this year and he’ll come, receive them and immediately leave, cheers! A flash of his recognisable jester’s grin.

That whole incident just made him feel sorry for people who get cancelled on the internet and angry that people claim to care so much about said cancellation or issue of the day, when they don’t really care at all, otherwise they’d be out in the streets protesting and discussing it beyond that day or week and… “Now I’m going back over it,” he realises. “That’s the only thing that frustrates me towards it: I shouldn’t have had to explain myself as much as I did. I didn’t have to answer to anybody but myself. People are always going to hate.”

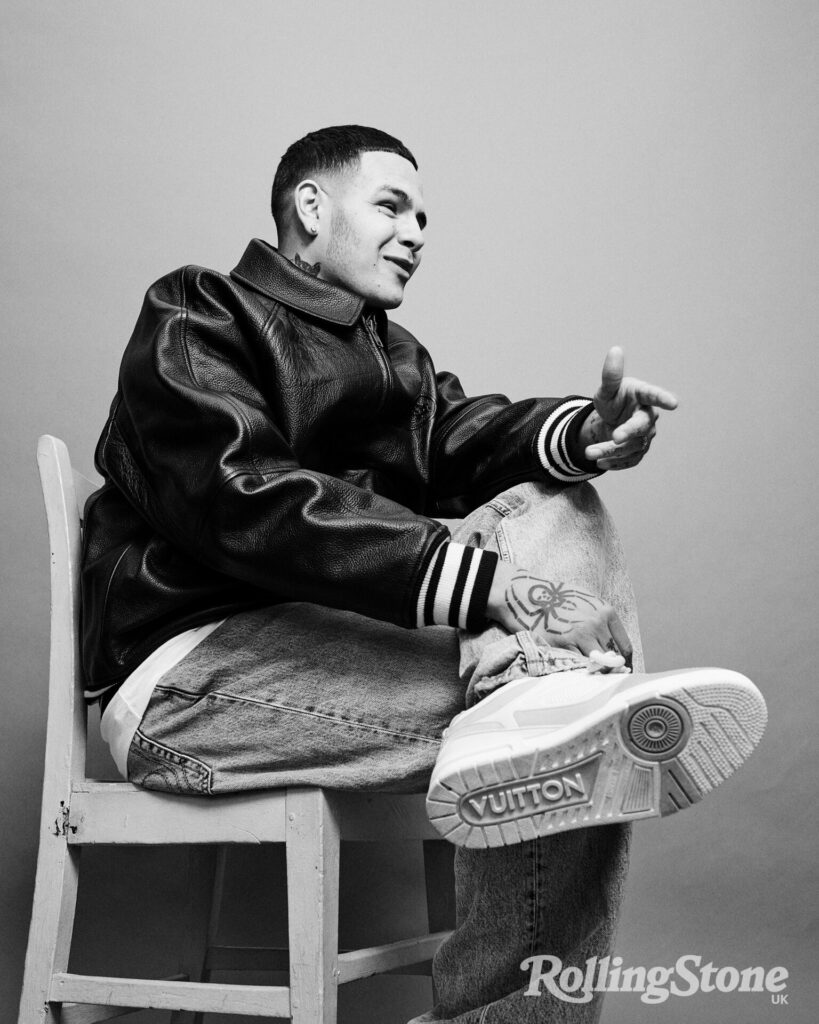

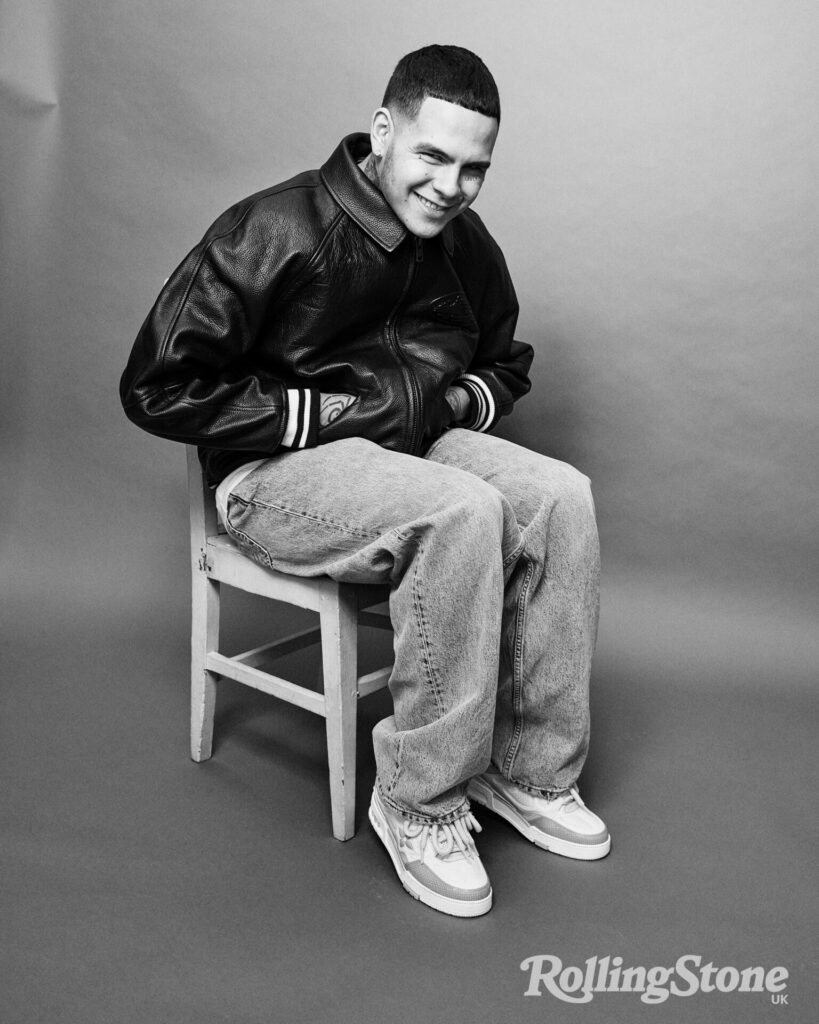

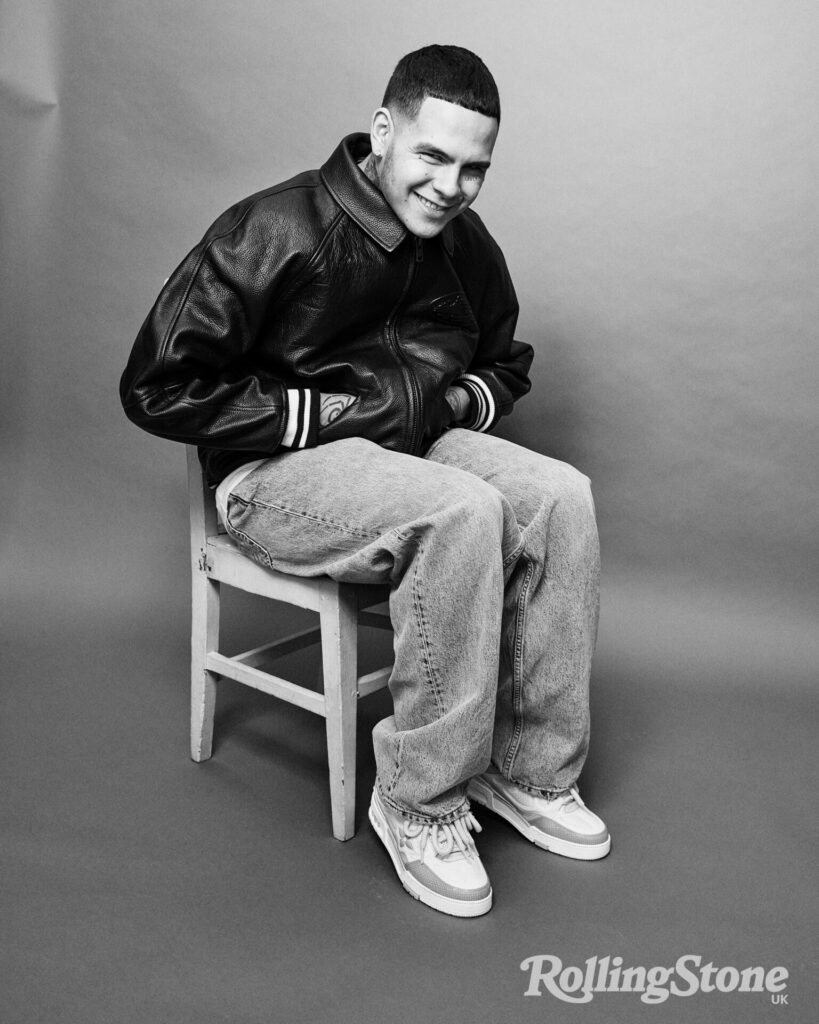

Point is, what could therapy do for someone like 28-year-old Frampton? He transforms rooms with cheeky energy, both the naughty kid and social lubricant, someone who could break bread with lords or peasants. He says he gets depressed but it’s hard to imagine that state coming over someone so gleeful. His relationship with his mum is very close. Not settling for gifting her a large house back in his hometown of Northampton, now he’s given her a second home nearby that he originally bought for himself (“It does more for me her having it than me just being in an empty house,” he shrugs). He’s immensely endearing, frequently laying claim to clichés and colloquialisms, making them sound more box-fresh than his trainers (“It’s like I always say, every dog has his day,” he says about U2, for some reason; “It’s that saying I always say: you can lead a horse to water but you can’t make it drink,” he says about people from Northampton being stuck in regressive ways; “It’s what I say, life is like a box of chocolates,” he and Forrest Gump both say about the fluctuating human existence). You meet him and leave thinking, ‘Now that is an absolutely sound guy.’

Another pre-existing tool for the promotion of mental well-being is that he knows how to self-express. Since entering the British music market with songs about the Conservative party, class struggles and the late Queen being a c*nt, the rapper’s music has scaled aggressively in ambition while capturing something about our domestic experience as the late empire crumbles, along with the NHS, public services and anything else that made living here an attractive prospect. His second album, TYRON, made number one on the UK albums chart and featured songs with Skepta, James Blake and Mount Kimbie. This one, UGLY – which stands for U Gotta Love Yourself, an acronym he now has tattooed under one eye – is his best track-for-track yet.

Given all that, his conclusive remark on therapy is: “I got enough people to talk to, why am I paying for it?” It’s a good point. What Frampton did inadvertently learn from doing – and quitting – the whole exercise is that he needs to be brutally honest with those who knew him before he had money and success. “Sometimes we don’t say things to people because we don’t want to hurt them,” he says. “With some people, I don’t want them to think of me differently. But now I’m at a point where I’m a dad, I’m like, ‘Why would I lose sleep at night if I’m just being this realest version of myself?’ If they really care, they’ll still be there.”

You’ve got to prioritise yourself to a certain degree for self-betterment, which is exactly what his first single from UGLY is about. For the video for ‘Selfish’, Frampton tried to spend 24 hours in a mirrored cell and managed most of that. His team could look in on him, but he only saw himself. He smoked cigarettes, wrote a short story, made some art and watched the paint dry, literally. “I kept thinking of all my friends in jail. They obviously ain’t in there out of choice, and then I am, I’ve put myself in a mental prison,” he tells me afterwards. “It’s weird, though, because before I got in there, I felt like I had so much in my mind. But when you’re surrounded by mirrors and under that bright light, my head just became clear.”

As clear as what music does for his brain. That’s what really saves people, what we’re really here in the fake therapeutic set-up of an interview to discuss. Frampton has a collection of songs he puts on when he wants to lift his spirits: ‘Just the Two of Us’ by Grover Washington Jr. feat. Bill Withers, ‘Salad Days’ by Mac DeMarco, ‘Just’ by Radiohead and ‘My Way’ by Frank Sinatra. One of the tracks on his new album – the ironically happy song about suffering, ‘Feel Good’ – is designed to be one of these. Play it when miserable and shift your mindset while singing and stomping along with the upbeat instance “I feel so good, I feel so good, I feel so good”. Speaking of music, there’s one last thing he’s discovered that’s better than therapy: playing instruments and making rock music.

It might surprise you that slowthai always wanted to be a rock star. “Being from Northampton, it’s a band town – or it was when I was growing up,” Frampton explains. “There was more bands than there was rappers. I always wanted to be in a band, but no one would give me any opportunities. I liked rock more: guitars and that instrumentation was the thing that I was more drawn to over 808s.” Here he was with two of the greatest entry-points to teenage socialisation (having an older brother and selling weed), cheat codes that gave him access to lots of different groups of people, including skaters and indie kids, and none of them would give him a shot, musically speaking. As a big fan of Nirvana, Radiohead and Daniel Johnston, he’d try to get involved with their musical projects, angle to be a frontman or offer up ideas when he dropped into one of their houses. “I don’t think they ever took me serious in that way,” he says. This gatekeeping continued when he did music technology at college. Students with guitars and drum kits didn’t want to know and Frampton was pushed further down the route to rap.

“Everyone who didn’t accept me, now they want to be part of my band”

“Everyone who didn’t accept me, now they want to be part of my band,” he says in a reflective moment of restitution. “I suppose without me being turned away – whether it was as harsh as I see it or whether they just genuinely wanted to crack on with what they were doing – it motivated me to get to where I am now, to where I can make an album that I truly want.” What about all of those band kids, those disbelieving college teachers who thought he’d never make it in music? “Not to put anyone down, but some people just don’t got ‘it’. Or the hunger.”

He’s had elements of rock in his music before. ‘Doorman’ featured distorted vocals, grumbling guitars and class commentary more punk than punk had been in years. He collaborated with rock duo Slaves (now called Soft Play). The intensity of the music, the political messaging, and his caustic delivery meant the P word was frequently used to describe his place within UK rap when his career launched: he was the punk prophet of grime. But UGLY is different altogether.

It’s slowthai doing alternative rock-rap, leaning back into the cutting and inventive nature that made people love him in the first place. This album – post-punk, raw – is what he says his first would have been if he had had access to those musical spaces he longed to be a part of. “Writing these kinds of songs is different to writing a rap, but at the same time, I’ve brought my formula of rap to rock,” he says. “That’s my twist on it, I suppose. Because it’s not singing but it’s not rapping either. I just feel it’s the way I could articulate my emotions better than rapping.” The creation of UGLY gave him confidence in his playing across guitar, drums and piano (“I always thought I was shit”) and delight in feeling he finally gained respect from people within the rock scene, namely Dan Carey (producer for Fontaines D.C., Black Midi, Chubby and the Gang), who produced this record, and Fontaines D.C., whose miserable instrumental contribution provides urgency to his incisive lyricism on the title track ‘Ugly’.

Another notable shift is that this is not a particularly political album, beyond reflections on the Russian-Ukranian conflict on that title track. “That label is a pigeonhole: You’re a political rapper. Then if you don’t say anything political suddenly you don’t care about this stuff anymore,” he says of this observation. “What would I do now, write about Matt Hancock on I’m a Celebrity Get Me Out of Here!? It’s art and it should be an expression of how I’m feeling at the time rather than necessarily this one thing. Like, it’d be pretty corny if I just rapped who’s the next prime minister of the country and the shambles of it.”

Instead, this is his personal album about feeling like a depressed man in a depressing world and fuck my therapist and his breathing techniques and I’m going to pull myself out of my mood with a changed and forced positive outlook and so could all of you listeners.

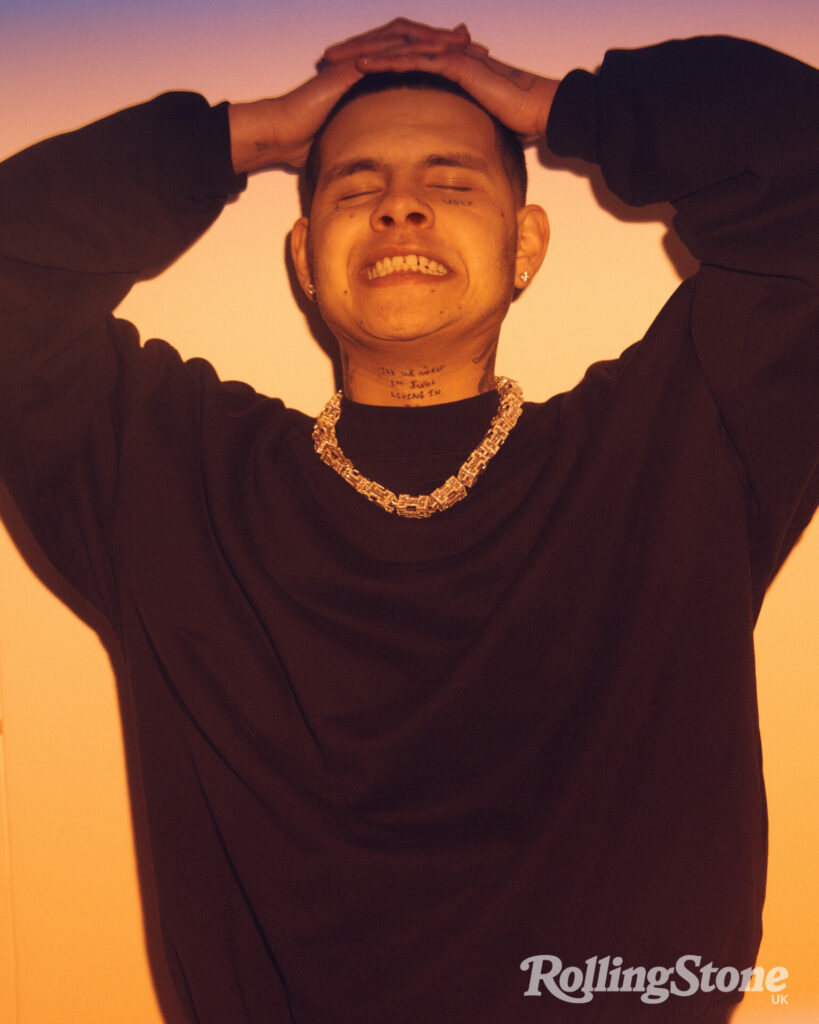

The name of the album is about having to love yourself because ugly to Frampton isn’t about aesthetics, it’s about a feeling. When you feel ugly, everything looks ugly. He’s recently been asking friends and musicians he admires what ugly means to them. His favourite answer, he says, getting out his phone to read off it, was this: The word ugly describes anything that is clashing to the extreme. Any one thing that goes against the rest. If you’re able to get far enough away from it and take in more information the ugly elements balance out into something natural and not what I would call ugly at all. When I ask who said that, his reply is teasing. “I can’t say. That’s one of the best voices of our generation and everyone’s waiting on his album.”

slowthai fans will note that his songs circulate familiar ground: the idea of wanting to escape where you’re from and self-destructive working-class vices. “It’s what is glamourised and glorified in a lot of music and television and you don’t have means to live any other way so that’s how you get your thrills,” he says. Opening track ‘Yum’ lists these out – getting head, titty fucking, snorting powder, blue pills, losing composure, dancing like nobody’s watching, more everything – and Frampton clarifies them for me: “It’s about all kinds of addiction, be it drugs, partying, money, sex, wasting time, turning your back and not dealing with your problems, lying to the people you love. All little things but they all amount to something and there’s stuff we blame on other stuff and we don’t take accountability for things we’re doing. But it’s through accountability that you can get out of it.” These transgressions are juxtaposed with interactions with his therapist who tells him to breathe until the song culminates in some kind of panic attack-orgasm-cry of exasperation.

Frampton never truly loved that hedonism – or, at least, can’t enjoy it without acknowledging the spectre of the hellish reality it creates when sustained as something resembling a lifestyle. Becoming a father was another step in maturing out of self-indulgence but spending days or weeks in Northampton means being around people invested in that old version of you: friends, acquaintances and people who think you owe them something because you chatted to them once at a house party. “It’s just a cycle that’s repeated. People do what the person before them done. And you’re trying to escape it and the rest of the people are pulling you back. And then eventually that eats you alive. That’s why the track is called ‘Yum’,” he says of this ouroboros-like existence, and adds that therapy works similarly. Consume yourself, talk about yourself, return to the scene of the crime, pay and repeat.

He relates more to an “addictive personality” label than to ADHD, which he was diagnosed with at school. A song of devilish and pained personas, ‘Fuck It Puppet’ is named after what his therapist called that self-destructive impulse, a personified imp sat on Frampton’s shoulder. “I fixate on one thing and then I’ll just drop it. It’s like a kid with a toy. You have one toy and you love that toy but then you get another toy and then you forgot you even had it,” he says, and lists recent examples of this: spending money, forgetting he bought stuff, not caring about the stuff; getting obsessed with cooking then dropping it for takeaway; buying a house, spending all his time renovating, then losing interest and going travelling instead.

It’s these dramatic, conflicting desires that get him to a space where he has to reassess. He was there near the end of creating this album, when he was drinking too much and feeling its depressive effects. There’s a line on ‘Yum’ that you might mishear if you’re not paying attention, where Frampton talks about needing an “innervention”. “People have an intervention to stop you taking drugs or whatever. But with yourself, if you know you’re fucking up, you have an innervention,” he smiles. “It’s not a word I don’t think, I might’ve made it up, but you have an innervention where you do it yourself. You look inward and you go, ‘Check yourself, man.’ Then you’re like, ‘OK, I went into autopilot and I had to pull myself back into my body in some way but I’m awake now.’”

The greatest innervention arguably happens the day you become a parent. In the summer of 2021, Frampton had been at the hospital through the night to support his ex-partner who had gone into labour. While he waited, he watched David Attenborough, because what more can men do, really? Nine months was long enough to prepare for this life-changing moment but seeing his son, Rain, here on the earth, he was mesmerised, almost in disbelief. And then, because he’s a celebrated rapper, he had to immediately go to a shoot for Adidas on no sleep.

Everything about his son is a marvel to Frampton, just as the world itself is a marvel to someone that small, fascinated with leaves on the ground and the mechanics of toys rather than the toy itself. “That’s the one thing I want to protect, that innocence,” Frampton says, “but at the same time give him the freedom to figure stuff out for himself. Not crush his dreams or tell him the way things are. I can’t get angry – patience is what I’ve learned from him.” Co-parenting as a musician is good, different, strange. “It’s hard with what I do,” he explains, “I have to travel to give him the life I never had but at the same time, I sacrifice time with him to give him all the things I never had. He’ll have a better life than I ever dreamed of. He’s my main motivation. It gives you purpose, having a baby.”

He’s currently spending a lot of time in Essex too as he’s dating the popstar Anne-Marie who is based there. She watches along proudly as he does his album playback and comes along to this interview, perched alongside him on the couch, only leaving the room at the last possible moment. If you meet people who work in the public eye, you either experience their persona or you meet the real them, Frampton says. With her it was the latter. “When you connect it doesn’t matter about any of that [celebrity],” he says of their obvious common ground. “You can talk and vent about stuff, but I think the best thing is when you come home removing all that stuff and you don’t even think that you do anything else. Or you don’t even really need to talk about it.”

What he loves is the fun of their connection: “Just having a laugh. Coming from a similar place and being able to catch a joke. You get on a high. You either get on like a house on fire with some people or you don’t. And some people feel like they’re part of the furniture, that they’ve always been around and known you.”

In the vein of re-connecting with what made slowthai a special artist from the start, Frampton will soon play a string of pub shows for £1 a ticket (around his debut album he played shows for 99p and then for a fiver). To his mind, these cheap tickets will connect the live music with people who care the most. “Them people might not have the money or means,” he says. “It might cost them 40 quid to get to the show, so what, are you going to charge them an extra £40 on top? It’s from me and my cousin not having the money. It’s giving people that opportunity that we wish we had. If you can do it, why wouldn’t you do it? I just think some people don’t think like that. I think they just think, ‘Oh, I’ll grab every penny I can get from the fans.’” He’s aware that initially some of his live audience were cool kids, industry-adjacent people, posers who wanted to be seen liking the ‘right’ thing or the hyped thing. By his estimation, those people have filtered out and his fanbase is reflective of people who genuinely believe in him. Fans will understand that the shows for UGLY will be real punk rock shows.

One of his new songs will sound particularly monumental in that context. It’s the title track, ‘Ugly’: heavy and suffocating, it evokes the feeling of walking around town in the English winter when it’s spitting rain. “Said that you loved me, you make me feel ugly,” he rap-sings about a girlfriend over the noise of a core loss, an emotional punch in your gut, being unsure if you will ever be happy again. “I think some people never feel that way, they’ve never been to that level…” he says, nodding at this description. “I envy those people because they don’t understand the feeling of the world crumbling and that being the end of everything. That feeling is just consuming.”

He starts to describe the scene in Hayao Miyazaki’s Howl’s Moving Castle where a devastated Howl thinks he is losing his beauty and in response his house begins to morph, melt and turn black. That is the metaphor of your inner world becoming the outer. Frampton’s intention was to get so inside that feeling – any feeling, really – that he could create music that is the environment as he, the artist, sees and feels it.

When Frampton made that droning, desperate song in the studio with Dan Carey, he could have cried. He knew before but that’s when he really felt what the album was and how it should come together. That was how he had been feeling, that bad. That’s when he really understood that music could be his therapy and version of self-discovery. Together he and Carey played it in the studio again and again. It had the expansiveness of shoegaze, the devastation and doom of stoner rock, “really slow but heavy at the same time”. That’s when he realised he’d done the near-impossible. He’d made slowthai music that perfectly captured him at his naturally extreme and clashing, something that people don’t understand about him or manage to articulate: that he is a uniquely laid-back and totally abrasive person. It’s something you might call ugly, but that would be a matter of perception.