When London’s music scene took on the racists – and won

Rebel Music is a series of events celebrating the South East London borough of Lewisham’s legacy of activism and art. Rolling Stone UK explores how the city’s music culture galvanised a generation of anti-racist activists across the country

When photographer Syd Shelton arrived back in London in 1976, four years after leaving the UK to work in Australia as a photojournalist, he was shocked by the level of racism he saw in British life. “The Black and White Minstrel Show was prime time Saturday night television – everybody watched it,” he sighs from his studio in London. “Black, Asian and Irish people were always the butt of dumb jokes from comedians. There were signs in windows: ‘No Blacks, no Irish, no dogs. On top of all this, the fascist organisation, the National Front, were stirring up hatred on the streets. Racism was everywhere. It was an appalling situation.”

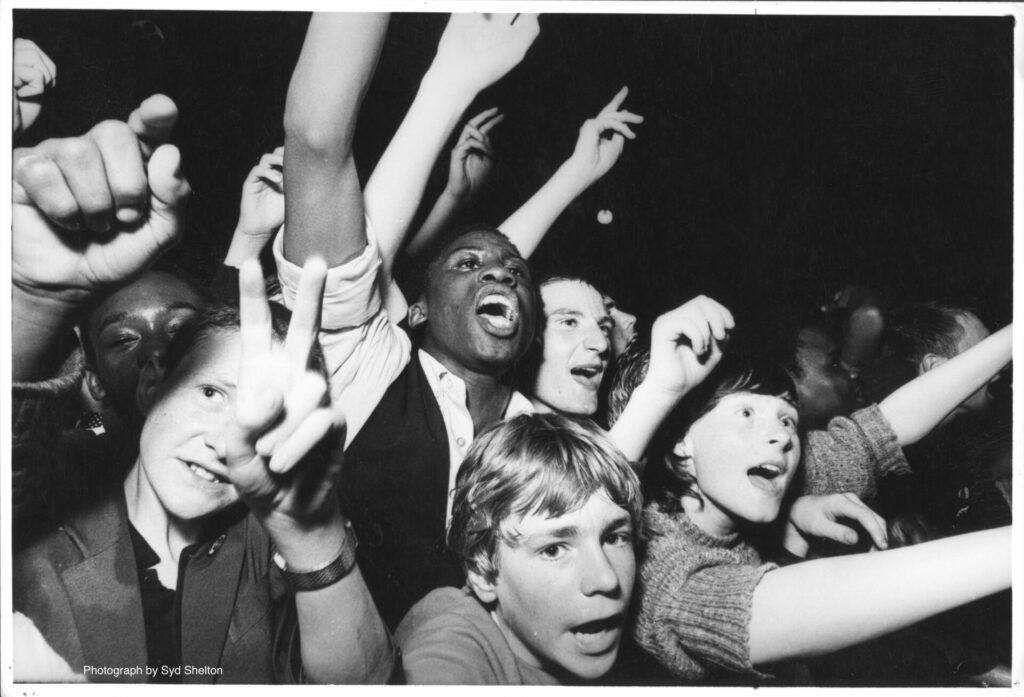

Soon after arriving home, Shelton started to visually document a new movement called Rock Against Racism (RAR), which aimed to bring communities divided by racism together through music. Rebel Music, an upcoming new festival (part of Lewisham London Borough of Culture 2022), explores RAR’s history and its links with the South East London borough, as well as London’s wider history of activism through music. Through Shelton’s photographs, a screening of White Riot (a film that explores the rise of RAR) and performances from some of the artists involved in the wider activism of the day (including dub poet Linton Kwesi Johnson and This Heat’s Charles Hayward), the festival shows how audiences united in the face of racism incited by the right-wing press, organisations like the National Front and even some influential musicians of the day.

“The spark which set the whole thing off with RAR was a speech by Eric Clapton,” Shelton explains, referring to an infamous inflammatory speech the musician gave at a 1976 concert in Birmingham, where he declared his support for right-wing British politician Enoch Powell and delivered what Shelton calls “a constant diatribe of racism”. White Riot filmmakers Rubika Shah and Ed Gibbs say that, while the speech was a catalyst for the movement, Clapton wasn’t the only musician with such view – in the film, they show that Rod Stewart also voiced his support for Powell, while at the time musicians like David Bowie said they’d like to see Britain being led by a fascist leader. “It was the fact these artists had a responsibility to their audience,” Gibbs continues. “And the outrageous thing about Clapton’s on-stage behaviour was that he was effectively inciting racial violence to the audience. It was a very scary time.”

In response to Clapton, the founders of RAR – Red Saunders, Roger Huddle, Jo Wreford and Pete Bruno – wrote an open letter to the NME, Melody Maker, Sounds and the Socialist Worker to voice their protest. “We want to organise a rank-and-file movement against the racist poison music,” they wrote. Just three months later, the first RAR gig took place and soon, concerts were happening all over London, becoming what Shah describes as “the sound of resistance”.

Shah says the RAR events – as well as other grassroots music events in Lewisham and other boroughs that emulated RAR’s principles – were all “multicultural events”. She explains: “There were Black, white, there were different religious groups, different community groups all coming together and standing up for something that was really important.” The line-ups of RAR gigs saw reggae and punk bands perform on the same bill as one another, often coming together at the end to jam. “Roger and Red were very vocal making sure that reggae artists were on an equal platform to punk artists,” Shah says of the gigs. “A lot of punk came from reggae, and they riffed off one another. At the end of the gigs, there would be jams where there was a real unity and inspiration in people coming together. Kids who came in as punk fans left as reggae fans, and vice versa.”

The situation on the streets, meanwhile, was dire. Racism was being stoked not just by the National Front, but by the authorities too. The Metropolitan Police’s ‘sus laws’ gave police the power to stop, search, arrest and detain individuals they merely suspected of loitering with intent, which disproportionately targeted Black communities. Shelton remembers how the Met frequently raided the houses of Black communities throughout Lewisham. “They raided houses all over that area,” he recalls. “They arrested young people, especially young Black men who’d been caricatured as street muggers.”

“There were Black, white, there were different religious groups, different community groups all coming together and standing up for something that was really important”

— Rubika Shah, director of White Riot

In 1977, the police arrested 21 young Black men, the youngest of which was 14, on spurious grounds. 16-year-old Christopher Foster was among those arrested. Syd Shelton went over to the area and visited Foster’s father, who was using the family sitting room as a headquarters for the ‘Free the Lewisham 21’ campaign. “It was in that atmosphere of trying to defend the Lewisham 21 that the National Front decided to put on an incredibly provocative march through Lewisham, which was called the ‘Anti-Mugging March’,” Shelton explains. The march was met by the community of Lewisham, who stood together against the NF – they were also joined by people from all over the country, as well as musicians. “It was a day of reckoning,” Shelton says, recalling how the Met sent officers armed with riot shields for the first time at a protest in mainland Britain. He was trampled to the ground while trying to catch the protest on camera. “The police came to give everyone a kicking, there was no doubt about that.” Outnumbered, the NF quickly dispersed, but the Met stayed for the anti-racist protestors. “The NF were very quickly bussed out the area – most of the day was actually a battle between the Met and the local community,” Shelton says.

The violence was widespread. The Albany, a Deptford venue that regularly hosted joint punk and reggae events, was burned down in 1978 after a suspected racially motivated arson attack. The New Cross Massacre in 1981 saw 13 teenagers killed at a birthday party after another suspected arson attack. While the community believed that this too was racially motivated, the police did not and dismissed the case entirely. Teacher and activist Blair Peach was killed at an anti-racism demonstration in 1979, the same demonstration at which Misty in Roots’ manager, Clarence Baker, was beaten so badly he ended up in a coma. The NF would even try to infiltrate RAR gigs.

“A year after the events in Lewisham in 1978 there was one gig with Sham 69 and Misty in Roots at Central London Polytechnic,” Shelton recalls. “We’d gotten word that the National Front skinheads were going to infiltrate and trash the gig. Misty organised a posse of really serious, and quite heavily tooled up guys to line the stage. They did get into the building, but they never got anywhere near that stage because we had it so well protected. Jimmy Pursey and Sham 69 did have a fairly large following of right-wing young lads, which they tried to shake off.” Pursey, frontman of Sham 69, received a death threat ahead of the second of RAR’s big summer ‘carnival’ events where he was due to perform. He pulled out of the gig.

“Jimmy went home that night to Plaistow where he lived and some young kid said to him, ‘You’re not doing the gig because you’ve got no bottle.’ That played on his mind all night,” Shelton remembers. The next day, Pursey turned up at the carnival, walked on stage and delivered a powerful anti-racism speech, disowning the racists who’d adopted them as a band and declaring their support for RAR. Shelton captured the moment on camera. “He turned around and looked at me,” Shelton recalls. “I’ll always love that photo. He was in tears and his brow was totally furrowed. It was a decisive moment in front of 150,000 people.”

“It brought reggae music and punk music together and it brought white kids into Black culture“

— Linton Kwesi Johnson, dub poet

Legendary dub-poet and reggae musician Linton Kwesi Johnson says things started to change following these events. He recalls more reggae artists being on punk bills – not just at RAR, but now in the wider grassroots music scene. “I think it was an important intervention because it brought reggae music and punk music together and it brought white kids into Black culture,” he explains. “It was a great way of sharing our common dilemmas at the time because youth unemployment was huge and as devastating for Black kids – well, even more so than for white kids. We’re talking about the Thatcherite years and the cuts. It was important in making young white people aware of racism, and it was also important in bringing about working-class solidarity between young Black people and young white people.” Shelton says the class struggle brought about another level of solidarity and unity between the audiences that cut across racism. “The class struggle was absolutely crucial to [the movement],” he says. “It was coming from the estates, from the suburbs, and that was the place RAR was most successful.”

Johnson performed alongside punk artists like Siouxsie & the Banshees and Ian Dury & the Blockheads. He says while he was always welcomed at the gigs, he wasn’t sure what to expect at first. “The first time I did a gig with Johnny Rotten was at the Rainbow in December 1978, and when I walked on stage I almost ran straight off again,” he laughs. “I saw this huge crowd of punks, with the safety pins and the funny hair styles. They were spitting at the stage. Apparently, that was a compliment. If they said things like, ‘You’re the dog’s bollocks,’ that was also meant to be a compliment. I didn’t know that at the time – it was a little bit frightening!”

Johnson, who arrived in Brixton aged 11 after travelling from his home in rural Jamaica to be with his mother (she was a part of the Windrush generation), says reggae music spoke to punk and fans of experimental music because of the language of protest the genres shared. “One of the defining characteristics of reggae music is [how] it’s always been a socially conscious music,” he explains. “In a sense, during the 70s and 80s, it was the voice of the people of Jamaica and the diaspora.” He continues: “There was a strong, for want of a better word, protest element in that music.”

Charles Hayward, drummer with influential South East London band This Heat, remembers playing two RAR gigs and being welcomed by both punk and reggae musicians, despite his band’s music being more experimental, made in the vein of German experimental rock bands like Can and Neu!. He says their music was welcomed as it was another form of protest against the norm. “Those gigs were a sort of heaven for us because probably the only other UK musicians who we felt an affinity with about the strangeness of sound was the dub musicians, the reggae musicians. We felt in some way they were our fellow travellers with bass and rhythm,” he explains, saying he frequently performed with reggae artists in Lewisham and later, all across London as the popularity of gigs with diverse line-ups grew. “We got the opportunity to make a sort of rebel music on those stages. In the music, we expressed the place that we wanted us to be, as opposed to the place we were. It was the idea of sound as a thing that could change the world.”

“We got the opportunity to make a sort of rebel music on those stages. In the music, we expressed the place that we wanted us to be, as opposed to the place we were“

— Charles Hayward, musician and sound activist

From its humble beginnings in small London venues, RAR grew and organised a summer of carnivals, the first of which ran from Trafalgar Square to a concert in Victoria Park, to an eventual audience of 80,000+ in 1978. Two more followed a few months later – one in Manchester, another at Brixton’s Brockwell Park. By the end of 1978, RAR had organised a further 300 local concerts and a Militant Entertainment Tour, featuring 40 bands at 23 concerts across the UK. The numbers at the gigs were astonishing, particularly in the analogue age. The group embodied the DIY aesthetic of punk, spreading word of their events through their influential fanzine Temporary Hoardings, flyers, posters, ads in the music press and through teaming up with organisations like the Anti-Nazi league. Shelton says the first carnival epitomised everything that RAR was about.

“We wanted to do something that was not a demonstration or a free concert,” he explains. “We wanted to take over London for a day, so we booked Victoria Park in Tower Hamlets, which is where the National Front had got 13% of the vote in the previous Greater London council election. We were taking it to their home ground. We wanted an anti-racist Woodstock, we wanted a seven-mile-long street party.” This event got artists on board like the Tom Robinson Band, X-Ray Spex, Steel Pulse and the Clash. None of them had ever organised anything on this scale. “We were all worried. We didn’t know what we were doing. We’d never done anything like this before. Nothing like this had ever been done.” They were worried it was going to be a failure: at 7am on the morning of the first carnival, 10,000 people were already at Trafalgar Square. Coaches coming from all around the country carrying thousands more followed. By night-time, there were over 80,000.

Gibbs says the legacy of the movement, which ended in 1982, can still be seen today. He points out that “Love Music, Hate Racism has developed out of RAR and it’s still very active around the UK.” Meanwhile in DIY, grassroots and independent scenes, there has been a conscious shift to introduce more diverse line-ups – although there is always more work to do, gig spaces and stages are, by and large, seen as places where racism is not tolerated. “It’s actually really inspiring to see that there’s lots of activism still going on and there are loads of young people out there determined to make a difference and refusing to allow injustice in the world to continue,” Gibbs adds. “At the end of White Riot, we say that the fights not over, and it never will be. The thing with racism is that it’s always just under the surface. Look where we are today: it’s all come roaring back.”

“It was an empowering time,” Shelton says of the ‘rebel music’ movement. “I remember Tony Benn once saying that there is never an ultimate victory, you have to keep fighting. Racism is this insidious idea that comes out of the sewer and you’ve got to fight to put it back in the sewer all the time. People aren’t born racist, they learn it from things like The Daily Mail, the Daily Express and The Sun, the drip-drip-drip of Nigel Farage and Donald Trump and their ilk. We have to guard against it constantly and fight against it,” he says solemnly. “It doesn’t go away.”

Rebel Music, part of London Borough of Culture 2022, runs across multiple venues in Lewisham, South East London, from May 5-22