Portrait of a Lady: Cate Le Bon on catastrophe and new album ‘Pompeii’

For her latest record, Cate Le Bon recorded right at home: Cardiff. The formidable record affirms her status as one of the most enthralling musicians of our time

By Emma Garland

The view from the house Cate Le Bon is staying in looks like a Bob Ross landscape. She angles the laptop so I can see the floor-to-ceiling windows overlooking sun-bleached hills that stretch for miles in every direction. The sky is swimming-pool blue, the mountains a mosaic of flora and scorched earth. The 38-year-old Welsh artist moved to Los Angeles back in 2013 and now lives in Joshua Tree, but when we speak in early January she’s in the bohemian enclave of Topanga Canyon — former home to everyone from Jim Morrison to Charles Manson — producing an upcoming record by Devendra Banhart.

“It’s been, like, this lovely suspended reality,” she says, Carmarthenshire lilt still intact. “When I lived in LA, I used to wake up early and drive out here two or three times a week. There’s this bend in the road as soon as you come out of the mountains, and the ocean is right in front of you. You know it’s coming, but you don’t really expect it, and then you just go” — she pauses to gasp — “There she is!”

This description also applies to Le Bon’s music, which is full of small miracles in the form of subtle yet startling movements. Since emerging through the Welsh indie scene in the 00s, she has staked out a reputation as one of the most compelling artists of a generation. Her five albums to date have been experimental free-for-alls ranging from psych-folk to spacious avant-pop, always anchored by her voice, clear and resonant as church bells. For her 2009 debut, Me Oh My, Super Furry Animals percussionist Krissy Jenkins gave her free rein of his studio for several months, while 2019’s Mercury-nominated Reward was written in a cottage in the Lake District. Each has been made in cloistered circumstances that do their best to replicate a childlike state of creativity: making something because you want to, with as little interference from ego and audience as possible. It is this that often tips her work into the realm of the surreal.

“It’s been, like, this lovely suspended reality,”

This unique balance of playfulness and precision has seen her called to collaborate with artists like Perfume Genius and Deerhunter’s Bradford Cox, produce records for artists like John Grant, and join John Cale for a stretch of shows in Paris. “She really is a one-off,” Nicky Wire of the Manic Street Preachers said of Le Bon in a recent interview with The Line of Best Fit. “She’s always doing something interesting, even if it throws you off the scent a little bit.”

Despite the accolades, Le Bon keeps a low profile — or at least the illusion of one. “I’ve always flown way under the radar, so I don’t think anyone’s really expecting anything from me, which has been quite freeing. You’re able to do what you want to do without disappointing that many people,” she laughs, with characteristic Welsh humility.

In recent years, Le Bon has pulled away from social media too, which has helped seal the vacuum she prefers to work in as well as adding weight to the prospect of performing live. “I’m more excited about seeing the people who want to see me play, and that being the moment where we all have this experience in the same room. It’s not diluted by, like: we just had that amazing experience, now here’s a photo of me eating a crisp in a van.”

For all the intent behind her principle of creative isolation, the circumstances of Le Bon’s upcoming sixth album, Pompeii, were dictated by outside forces. When the pandemic began, she was in Reykjavik working on John Grant’s Boy From Michigan. Rather than scrambling to leave, she stayed in Iceland for another two and a half months. “It was maybe the best place to be,” she says, inadvertently painting a picture inverse to the UK, “on this really civilised island where people had been preparing for this for a long time.”

When Le Bon did return to the UK, it was to her childhood home in Penboyr, where she spent the summer of 2020 enjoying the uncharacteristically good weather and hanging out with family and friends. “It was with this expectation that the American borders would open soon,” she remembers. “But waiting for that to happen was becoming so exhausting that it was stopping me from making actual plans that I could execute.”

Knowing she was ready to make another album, Le Bon and her long-term collaborator and co-producer Samur Khouja had already been looking at studios around the world, in Chile, Norway, Costa Rica and Mexico. In the end, they decided the best place to do it was Cardiff. Khouja flew over in January 2021, and they set up a studio in the bedroom of a house that Le Bon had lived in 15 years ago. Every morning they would get up, go to buy coffee and groceries, then walk back to the house. “We treated that as a morning commute, so we didn’t go completely mental,” says Le Bon. Then they’d work for 12 hours a day. Le Bon’s partner, the artist Tim Presley, painted in the room next door.

It would be the first album Le Bon would record in Wales since 2012’s Cyrk, but the only sense of home was in the familiar layout of the house. “The idea of location and place was quite twisted. It was Cardiff, but I was FaceTiming my best friend who lives three minutes away. So, it was really just a room in a house, you know?” The album adhered to many of the same restrictions, relying on minimal input. Long-time collaborators Stella Mozagawa (drums), Euan Hinshelwood and Stephen Black (saxophones) were enlisted to work on the album remotely, and Le Bon played every other instrument herself. The result is an extreme version of her usual process; a collection of songs made not just by musicians isolated from the world, but from each other.

Early on, Presley showed Le Bon a painting of a woman — quite abstract, just bigger than A3 — that would have a gravitational pull on the album. “It was maybe one of the most beautiful paintings I’ve ever seen,” she remembers. “It had this quality of both being ancient and modern at the same time. It was like ancient sci-fi or something. And then he said it was a painting of me.”

They hung it on the studio wall and played with the idea of making the music feel like the painting. The result is nine tracks that feel dreamlike and forlorn. Hypnotic bass lines provide “the spine of the record”, mingling with flurries of melancholic saxophones and synths inspired by 80s Japanese city pop. There is a sustained mood from start to finish, which makes it feel both like a moment in time and the full scope of time itself — something that reflects the pandemic experience, where entire months collapsed together into a blur of sourdough and panic, but also gestures towards the divine. “Tim didn’t really know why he painted it, he just painted it — and that’s kind of how I wanted the record to feel,” Le Bon explains. “Like it was just this thing that one day wasn’t there, and then one day was.”

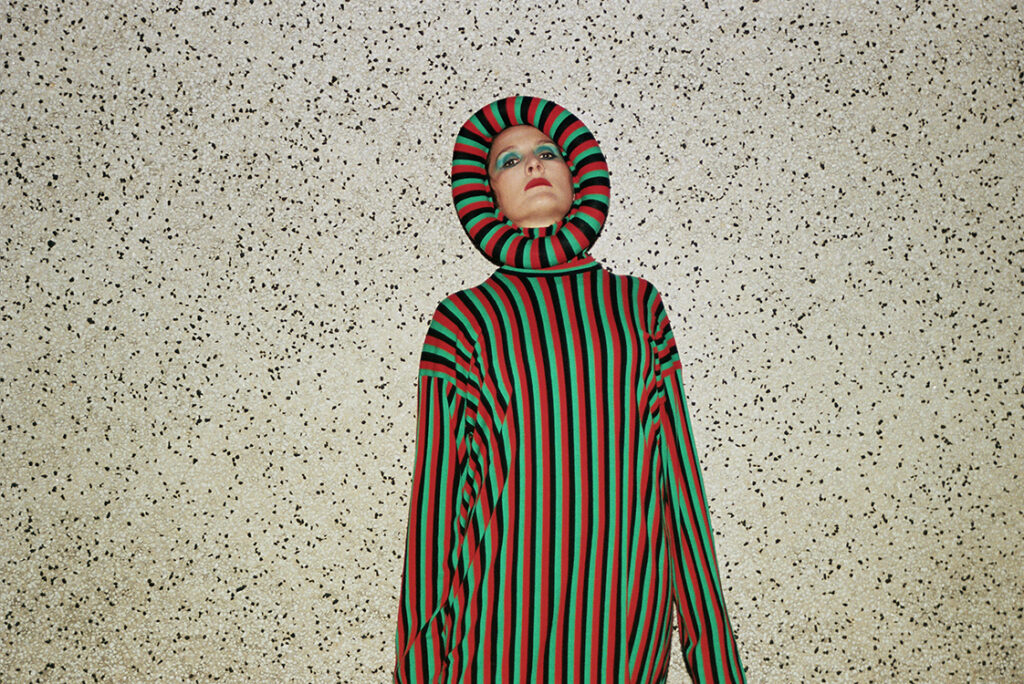

The painting took on a borderline religious and distinctly female presence, which has been interpreted and re-interpreted through different lenses. Rather than pull the painting out of context or attempt to reproduce it for the album cover, Le Bon uses herself as a stand-in. In the photograph she wears a wimple and a fixed expression, her fist raised to her chest like a Joan of Arc. Female sculptures abound in the video for ‘Moderation’, while Le Bon dances in an outfit that lands somewhere between a Victorian mourning dress and Karen O. In the video for ‘Running Away’, she casts saint-like silhouettes in various hooded cloaks.

“I’m not religious at all, but certainly your faith is challenged,” she says. “You try to figure out what your touchstones of faith are. I kept coming back to this idea that we’re all culpable for everything that’s happened, which smacks of this idea of collective guilt and original sin, which is so fucked up.”

Pompeii, then, felt like a fitting site for the album’s themes of connectivity and catastrophe. Le Bon had recently listened to a podcast about the eruption of Mount Vesuvius, but first learned about it at her Church in Wales primary school, where education was entwined with Christianity. As a child, the only way she could process it was to create an element of distance: “This is so horrible that it must be a Biblical tale.”

There’s a certain absence of logic required to deceive yourself like that, to protect yourself by not fully connecting with the terrors at hand. We’ve seen it over and over again these past two years. That absence creates room for absurdity, satire and surrealism, which are artistic methods of interpreting reality as much as they are tragic reflections of it. “Even though there’s a global crisis going on and we’ve probably never felt the repercussions of connectivity in this way before, still we find these tools to paper over pain and remove ourselves from certain situations,” Le Bon says. Pompeii, where time is literally frozen, bodies and buildings suspended in eternity, is an extreme example. “You’ve got this moment where this awful thing went down, and you can buy really tacky keyrings that say ‘I went to Pompeii’ in the worst font you’ve ever seen.”

This broken connection, ultimately, comes at a cost. There is a balance to the album that reflects the state of ambivalence we now find ourselves in. “It’s one of those periods of real duality, where extreme hope sits alongside extreme despair. And when the future is dark, anything is possible, right?” Those two things are constantly fighting out, in life and on the album. Though “the bass maybe tips it in one direction,” she adds, smiling.

Pompeii is out on 4 February