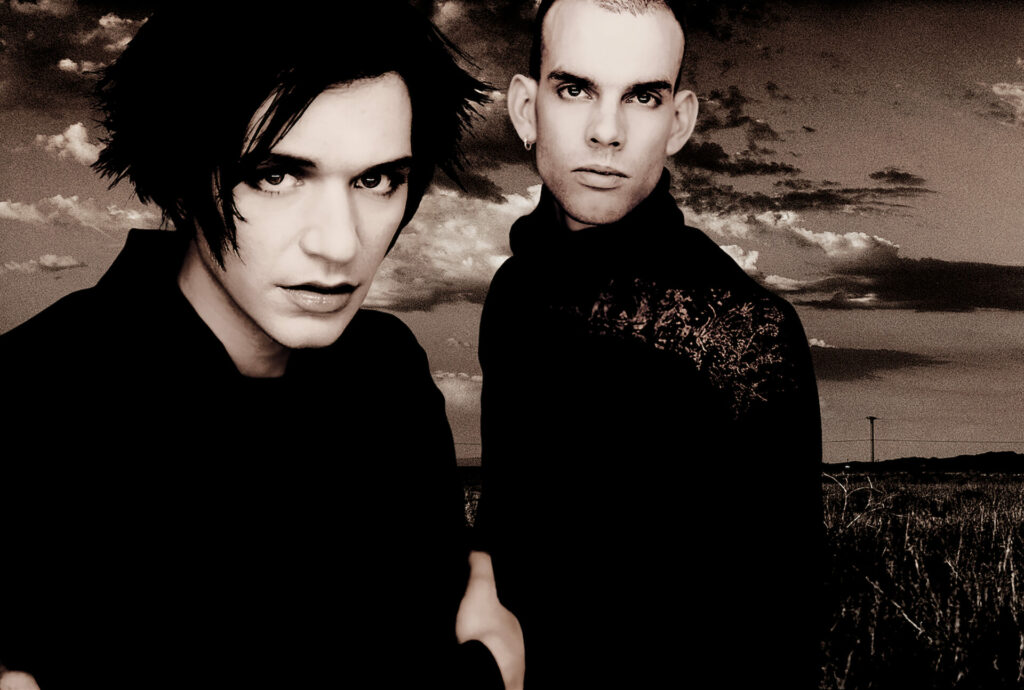

Placebo speak out on “brutal” return with new album ‘Never Let Me Go’

As Placebo return with 'Never Let Me Go', lead singer Brian Molko and co-writer Stefan Olsdal describe the thinking behind the band’s first album in nearly ten years

By Emma Garland

Somewhere behind a curtain of cigarette and incense smoke, Brian Molko wants to know if I have seen any recent pictures of Chernobyl. The table between us is cluttered with cups of strong black coffee, and the space — a cosy studio in east London, just below a room he rented during lockdown to write lyrics — is more like a hippie hangout than somewhere you’d expect to find the frontman of a legacy band like Placebo. The main light is off, the lamps are dim, the couches are covered with patterned throws. It’s 11 o’clock in the morning. “Brian will be smoking,” I’m told in advance.

“It’s overgrown with nature and animals have come back,” Molko elaborates, as he sits with his legs crossed, a cigarette balanced elegantly between two fingers, as it has been in press shots since the mid-90s. “Why? Because humans aren’t there. That’s my vision for a millennia from now — a planet where animals can thrive again, because we’re continuously destroying it in the name of profit.”

Unsurprisingly, these themes — ecological disaster, the scourge of capitalism, a profound disappointment with humanity at large — come up a lot in our conversation. They’re front and centre of Placebo’s eighth studio album, Never Let Me Go, which features a shoreline made up of curiously multicoloured pebbles on its artwork. Molko came across the image while reading about a beach in northern California that was used as a dumping ground for everything from cookers to cars, until a clean-up effort in the late 60s removed all the rubbish. In the process, locals discovered that all the glass had been rolled and tumbled by the ocean, creating the smooth kaleidoscope of stones you see on the album cover.

“I just thought, ‘What a wonderful story about how resilient nature is,’” says Molko. “And how much humans, as a species, shit where we eat. We destroy where we live. We’re the only species that does that. But, given enough time and the absence of humans, nature will just clean it all up.”

Due out in March 2022, Never Let Me Go is Placebo’s first album in almost ten years. Until COVID put a stop to the world, the time in between was mostly spent touring. A world tour of their previous album, 2013’s Loud Like Love, immediately gave way to another, celebrating their 20th anniversary as a band. To the delight of their devoted audience of teenage goths, adult misfits, and millennials who learned the meaning of “special K” and “burger queen” from Molko’s lyrics, the reflective shows saw them dig out hits like ‘Nancy Boy’ and ‘Pure Morning’ for the first time since the mid-00s. Then, after five long years on the road, Placebo hit a wall that almost broke the band completely.

“I had reservations coming into this record based on the experience of touring,” says co-writer and multi-instrumentalist Stefan Olsdal. “It felt like we were slowly killing ourselves, and I just didn’t know how much life I felt there was left in the band. My confidence was at an all-time low.”

“We have a tendency to do a lot that we’re asked to do, regardless of how it’s going to affect our physical and mental wellbeing, so we continued touring,” Molko adds. “By the end of it, I felt like a performing monkey that was being moved around the world; kind of detached from the soul of it.”

Ever since Placebo burst out of south London in 1994, all angular noise and androgyny, they have been in a world of their own. Their early songs dealt with teenage angst, mental unravelling, heavy drug-taking, gender confusion — all with the air of tragedy and the pulse of desire. Their sound was simultaneously melancholic and urgent, performed at a speed that suggested they were desperate to get to the other side of something.

Influenced by British post-punk and new wave, plus experimental rock bands like Sonic Youth and The Velvet Underground (Molko attended Goldsmiths College after finding out John Cale went there), Placebo arrived as the 90s were drawing their last hedonistic breath. The band’s self-titled debut album, written mostly in a council flat in Deptford and released in the summer of 1996, hit no. 5 on the UK album charts, catapulting Placebo into the limelight at the commercial height of Britpop. Amid a sea of lads in sportswear, Placebo — with their lipgloss, tiny T-shirts, tongues curling around swear words the way you’d curl a lock of hair around your finger — stood out like wild cats in a darts club, swiping at all that was macho and sterile about British society.

Even in an overwhelmingly counter-cultural era, they were aliens. This wasn’t a free rave-attending, flannel shirt-wearing, smoking-while-accepting-a-BRIT-Award kind of rebellion. This was doing a full face of make-up and singing about queer sex over the most driving, blown-out wall of sound this side of My Bloody Valentine. It was music spawned directly from the underbelly, smuggled into the mainstream through sheer force of pop songwriting.

“Since we were kids, we haven’t really found a way to fit in anywhere,” says Olsdal. “So our process of searching led us to a point where we just created our own world.”

“It felt like we were slowly killing ourselves, and I just didn’t know how much life I felt there was left in the band. My confidence was at an all-time low.”

Placebo’s enduring success is partly down to the unique partnership that co-founders Molko and Olsdal, now in their late forties, have fostered for more than 25 years. The term ‘kindred spirits’ comes to mind. As songwriters, Olsdal’s formal music training and knack for arrangement complements Molko’s more abstract approach (having suffered from bouts of insomnia since puberty, Molko often writes in a semi-hallucinogenic state of sleep deprivation: “There seems to be a crazy sensitivity that manifests itself,” he explains. “I don’t know why, but melodies will come when I’m at my weakest”). As people, they are very similar — softly spoken, a little shy, with a mutual love of outsider rock stars (PJ Harvey, Björk, Grace Jones, Bowie) and a deep respect for what they have built together.

Molko and Olsdal attended the same school in Luxembourg (Molko was born in Belgium and grew up in a rural village in Luxembourg; Olsdal was born in Gothenburg and moved to Luxembourg at a young age), but it wasn’t until they relocated to London that they met by chance outside a Tube station.

They began writing as a duo, using cheap keyboards and guitars with missing strings. Olsdal’s childhood friend Robert Shultzberg joined them on drums in 1994, but left shortly after the release of their first album. The band has had a revolving door of drummers ever since. Steve Forrest, Placebo’s most recent drummer, handed in his resignation a few years ago.

At the eventual end of the 20th-anniversary tour, Placebo found themselves at a fork in the road: put out another album, or stop. They were burnt out and disenchanted, but Molko reacted very strongly against this feeling. “No more bullshit, Brian,” he said to himself. “Come on, focus.”

When it came to writing Never Let Me Go, Molko and Olsdal found themselves back where they started: just the two of them, surrounded by instruments (though slightly more expensive, this time), playing with noise.

For this album, Molko’s instinct was to spit out the taste of exploitation that touring had left in his mouth. “I wanted to do something that had a certain brutality to it, either sonically or lyrically,” he says, referencing one of his favourite albums, Kanye West’s Yeezus, as an example of commercial music taken to the extreme. What actually came out was something more “listenable” than they had intended. Thirteen tracks of metallic stoner rock, post-punk and gorgeous piano melodies, Never Let Me Go feels like Placebo’s strongest album in years.

Opener ‘Forever Chemicals’ throws you off-balance immediately with a sound that’s hard to place; a series of notes that sound like church bells in a cyborgian future (it’s a drum pattern, run through a harp pre-set with an overlay of distortion). It was the first thing they wrote. “There was something about that loop which was a real statement of intent,” says Molko. “It’s melodic and it’s catchy, but it’s also a bit brutal. It was a ‘start as you mean to go on’ moment for us.”

“I wanted to do something that had a certain brutality to it”

That tension is present throughout the album, which feels constantly on edge as it juggles intimacy and paranoia. Synth-heavy lead single ‘Beautiful James’ details a romance outside heteronormative confines, aching and anthemic. The initial inspiration for ‘Surrounded By Spies’ came from Molko’s discovery that his neighbours were spying on him, then bloomed to encompass modern surveillance in all its forms. “We sleepwalk through the city, unaware of the fact that you can be followed from your doorstep to your destination,” Molko says. “I thought to myself, ‘If good neighbours of mine can do this, then what else is going on?’ It’s just a microscopic version of what’s happening everywhere.” In response to that, ‘Chemtrails’ fantasises about disappearing from society after being “visible too long”, while the gloomy ‘Went Missing’ imagines someone who goes “missing for a living”. A sense of unease wriggles into every crevice of the album, even the silences, but there is a feeling of resolve, too.

Never Let Me Go was written in fits and starts — some of it pre-COVID, the rest between lockdowns in the UK, which offered the rare opportunity to put family before the band (and, in Molko’s case, binge all ten seasons of Curb Your Enthusiasm). In a way, the limitations forced upon the process by circumstance allowed longer periods of time for ideas to percolate, and more opportunities to revisit the songs with fresh ears. You can hear that space on the album, which contains more moments of silence than ever before. The sounds that are present are layered and unusual.

A lot of it came together in Olsdal’s home studio, where they worked amid a tangle of laptops, pedals, cables and boutique keyboards — the shape of the songs being dictated by their physical environment, as much as their headspace. “It really was a case of being in this kitchen with all these ingredients and using a bit of everything. I think we’re a band that just gets off on sounds,” Olsdal chuckles.

That sense of experimentation is present in the album’s visual language, too. The artwork is pixelated on one side like a digital image that’s struggling to load. The video for ‘Surrounded By Spies’ is shot from the perspective of CCTV cameras. Their faces — filtered and warped — appear on the artwork for the first time ever, for singles ‘Beautiful James’ and ‘Surrounded By Spies’. Nowhere in the material do you see Molko or Olsdal clearly, which feeds into the ever-present theme of surveillance, either by security cameras (London, after all, is the most surveilled city on Earth outside China), by your neighbours, or by your own hyper-vigilance. However, it was also a more practical choice.

“It was born out of a certain inherited shyness,” Molko admits. “We found ourselves after four or five years not really having done a photoshoot, looking around, and understanding that nobody puts a picture of themselves out into the world without manipulating it. We all hide, we all project an image of ourselves that isn’t really our true selves. And so the idea came to take this aesthetic and push it to the extreme, [to become] a very clear comment on aesthetics today.”

The album has been born out of a desire to do something totally different — something unlike Loud Like Love, something free from the 20-year-old material they had spent so long inhabiting on tour, which Molko in particular has a fraught relationship with.

“I always look back on what I’ve written and feel like I could do better, for a multitude of reasons: lifestyle, arrogance, being detached from reality, thinking that whatever you put onto paper is genius. That bravado and chemically induced confidence that I had in the 90s and the early 00s,” he says. “Now I look back and I kind of wish I’d been in the room more.”

It’s striking, then, that the upcoming album would have decidedly non-verbal origins. When Molko came across that image of the beach, he took it to Olsdal, and that’s when Never Let Me Go began to take shape. Not as a sound, or a concept — but as a feeling. Upon seeing it, Olsdal describes his initial reaction as one of relief.

“We all hide, we all project an image of ourselves that isn’t really our true selves”

“It just brought to me this space: an expanse where time didn’t exist, where other humans didn’t exist. It was just a beautiful scene where nature had taken its course,” he says. “No one to interfere, no baggage, none of our history, none of our troubles. It was almost like wiping the slate clean since the last album, which had been quite troubled — and the image represented that.”

For Molko, who’s suffering from “climate depression” and is so distressed by the political climate in the UK that he’s working on getting his European citizenship back, the image also represents how he feels about humanity in general. “Our obsession with acquiring wealth, this philosophical attitude that it’s actually something worthwhile, I think, will eventually render us extinct. And, in a way, I can’t think of another species on the planet that deserves it more,” he says with a cynical smile, adding that people shouldn’t take him too seriously, because “we need hope at this point”. Still, that doesn’t stop him wanting to “do a Lord Lucan” and disappear into the ether, like his narrator on ‘Went Missing’.

“More and more, I think I need silence and peace in order to rage,” says Molko. At the start of 2021, he left London after almost three decades and settled somewhere sleepier in Europe. “Hopefully in ten years you’ll find me on a patch of land on an island somewhere, bathing in rainwater and growing my own vegetables. That’s where I want to end up.”

The third issue of Rolling Stone UK is out now and you can buy it here.