The show must not go on: how artists are rewriting the terms of superstardom

Earlier this week, Miley Cyrus cited the stress of touring as the reason why she won't hit the road any time soon. Now more than ever, artists are establishing their own boundaries in the music industry – and aren't afraid to walk away if it doesn't work out

“Do I want to live my life for anyone else’s pleasure or fulfilment other than my own?” asked pop star Miley Cyrus in a recent interview.

The singer, who released her eighth studio album Endless Summer Vacation in March, was discussing the reasoning behind why she won’t be touring again any time soon.

“It’s been a minute,” she told Vogue of her live hiatus. “After the last [headline arena] show I did [in 2014], I kind of looked at it as more of a question. And I can’t. Not only ‘can’t’,” she self-corrected, adding that “can’t” is your capability, while her “desire” is a whole other matter.

The singer also explained that “singing for hundreds of thousands of people isn’t really the thing that I love”, adding: “There’s no connection. There’s no safety.”

“It’s also not natural. It’s so isolating because if you’re in front of 100,000 people then you are alone.”

Cyrus is not alone in this, a sentiment which probably seemed unfathomable to fans back when she was performing world tours of up to 70 dates.

It’s no secret that performing live in any capacity is an incredibly demanding lifestyle, requiring something entirely different from the very same artist who has probably spent months holed up in a studio recording their album.

But while recording and performing may seem like interchangeable responsibilities of any artist, it would be inaccurate to suggest that both hold an equal amount of weight – and require the exact same amount of energy – for the artists who do it.

In broader terms, musicians are often required to function at heightened levels that feels profoundly unnatural to many artists.

When SZA released her second album SOS in December – an artist whose debut, Ctrl, shifted the culture and redrew the boundaries of alt R&B – she also questioned if such intense creative bursts were sustainable. “I feel like music, in this capacity, I don’t see longevity,” she told Billboard.

“I like to create, I like to write, I like to sing, and I like to share. But I don’t know if chasing after superstardom or whatever I’m supposed to be doing right now is sustainable for me or for anybody. I’mma take a good swing at it, and I’mma give ’em my absolute best.”

She’s currently on her arena tour in support of the album, and she’s due to stop off in the UK next month.

Last year, George Ezra expressed his own struggles as he grappled with the commercial requirements of being a musician.

“This might be a conversation for another time, but I don’t feel an urge or want to continue operating in the way we do at the minute,” he told The Daily Telegraph last year. “And that’s not a rebellion, it’s just how I feel. Like, ‘Cool, that was a thing.’”

Ezra added that he thinks he’ll always write and record music, but didn’t know if “it’ll be as commercial”. He added: “Or maybe it will be but I won’t promote it much.”

When asked if he would miss touring for his fans, he shared: “Again, I feel so detached from it. It’s very hard to get your head around the fact it would be aimed at you.”

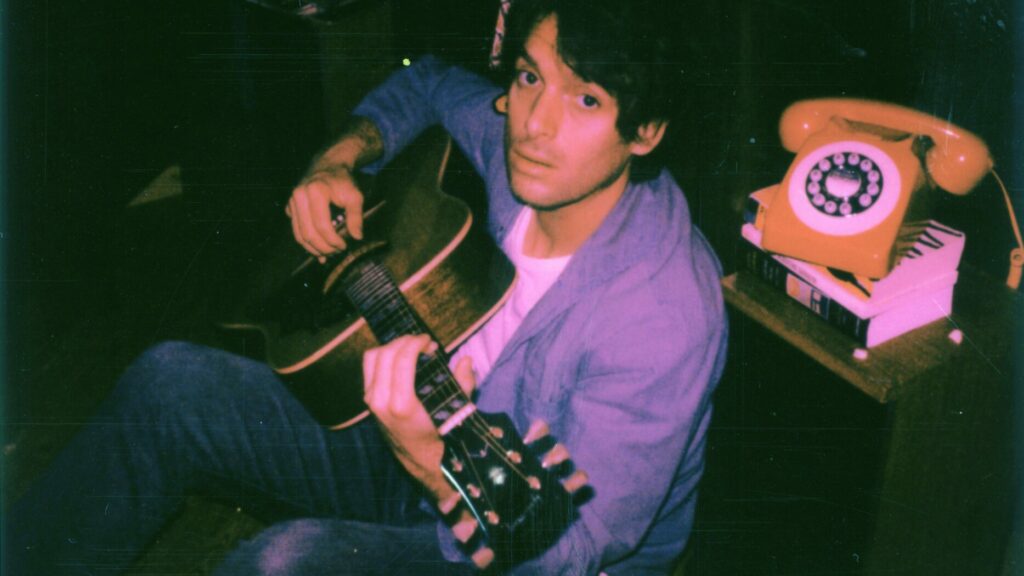

For other artists, the demands of the job are inherently tied to peaks and troughs in mental health. Lewis Capaldi has opened up on several occasions about struggles to overcome his Tourette’s syndrome, including in his recent documentary How I’m Feeling Now.

“My tic is getting quite bad on stage now,” Capaldi told The Times. “I’m trying to get on top of that. If I can’t, I’m f****d. It’s easier when I play guitar, but I hate playing guitar. I know, I’m a walking contradiction.”

“It’s only making music that does this to me,” he went on. “Otherwise I can be fine for months at a time. So it’s a weird situation. Right now, the trade-off is worth it.”

He too questioned if such a lifestyle could continue into the long-term. “But if it gets to a point where I’m doing irreparable damage to myself, I’ll quit,” he explained. “I hate hyperbole, but it is a very real possibility that I will have to pack music in.”

It seems for many artists, the struggle comes in managing the push and pull of wanting to make music for a living, while also fulfilling the terms and expectations of the commercial contracts that allow them to do it.

Musicians quitting, burning out, or withdrawing from the spotlight is nothing new. Lauryn Hill – who released her seminal, and only, album The Miseducation of Lauryn Hill in 1998 – said in 2001 that she “used to be a performer”, but didn’t consider herself one anymore. “I had created this public persona, this public illusion, and it held me hostage”.

But today’s superstars are performing in a world with far less privacy – one where fans not only want to know everything about their lives, but actually feel entitled to it.

There’s also the case that the modern music industry requires more of artists than ever before – whether it’s the pressure to be present on social media, or relentless touring and festival schedules post-Covid-19. Justin Bieber, Fontaines D.C, Wet Leg and Arlo Parks are just a few of the artists that have cancelled shows due to burnout and mental health issues.

Plenty of artists have withdrawn from the spotlight and returned when their own timing was right. Just last year, Paolo Nutini explained to Rolling Stone UK why he took eight years off. “The realities of doing this and the whole experience doesn’t feel entirely natural to me,” he said of performing.

“I’m not the most extroverted person, but when you’re on a stage you find yourself opening yourself up in that way. The more vulnerable the better, too, when you’re trying to give your audience a piece of you and you’re hoping to get something back. Once that ends, I’ve always had to recalibrate my f*****g brain.”

Artists like Cyrus, SZA, Capaldi and many more do seem to be changing the narrative about what a modern pop star looks like. And as younger listeners, particularly Gen Z, are more versed in the language of mental health, it means that stars are often met by floods of supportive comments from the most loyal of fans when they do open up about their struggles.

In a time where we’re experiencing hyper-saturation of social media content, the rise of AI in music and seemingly unsustainable expectations of instant interconnectivity, a little less formula and a hard break from expectation might be just what the industry needs – for the wellbeing of the musicians who uphold it more than anyone else.