Mustafa: beauty and all its flaws

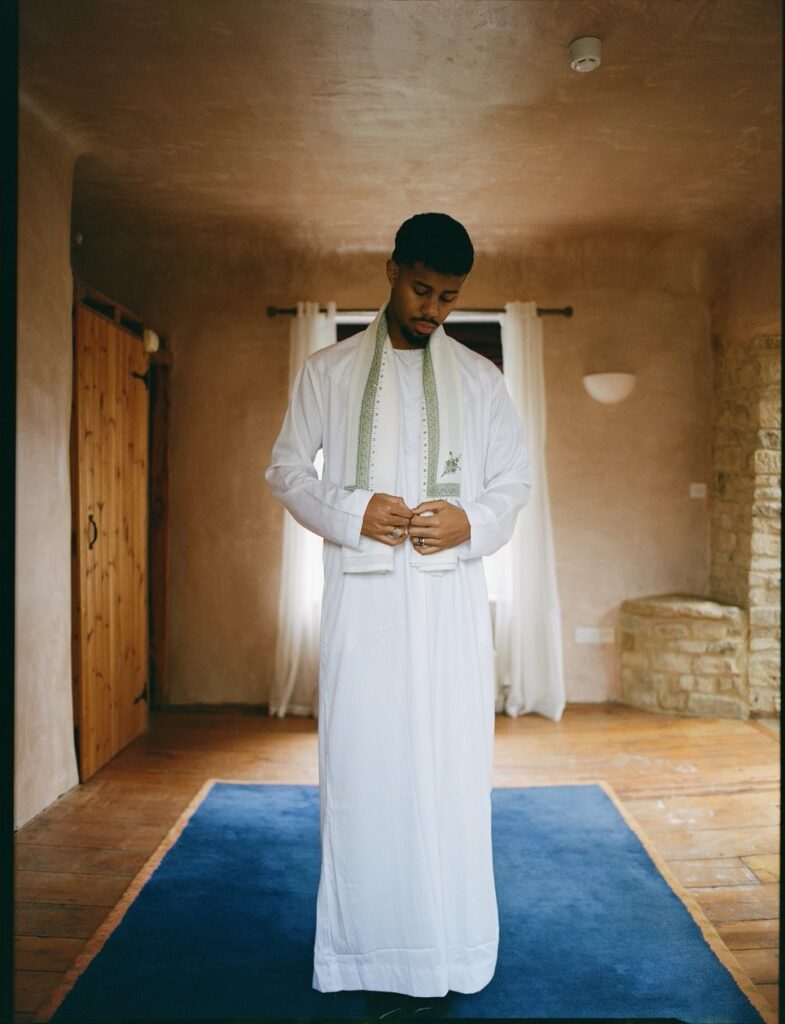

The prodigious Canadian-Sudanese poet-turned-folk singer truly arrives on stunning debut album ‘Dunya’, an exploration of faith, violence and hope with help from Aaron Dessner, Clairo and Nicolas Jaar… as well as the guiding words of Cat Stevens.

Dunya, the title of Mustafa’s debut album, translates roughly from Arabic as “the world in all its flaws”. Through this framework, the incomparable artist — who counts The Weeknd, Drake, James Blake, Rosalía and more as friends and collaborators — makes a huge first statement that sets him apart as one of a kind.

Born in Toronto with Sudanese heritage in 1996, Mustafa Ahmed grew up in the city’s Regent Park neighbourhood, the oldest community housing project in Canada. Beginning under the moniker Mustafa the Poet, he was first discovered as a 12-year-old after reciting a poem he had written at the Nelson Mandela Park Public School in Regent Park. The work, ‘A Single Rose’, was given a standing ovation at the Canadian International Documentary Festival in 2009, before he was named poet laureate at 2015’s Pan American Games. His work was shared by his city’s most famous son, Drake, and he was then nominated as one of 15 Canadians to join Prime Minister Justin Trudeau’s Youth Advisory Council.

In his teens, Mustafa formed the Halal Gang rap group with childhood friends including the rapper Smoke Dawg. He had previously worried that turning away from poetry and towards music would be at odds with his position as a Muslim community worker in his city, but he eventually began writing for others including The Weeknd, Camila Cabello and Justin Bieber. After going solo, he dropped The Poet from his artist name and began a new era as a striking, one-of-a-kind folk singer.

After the killing of Smoke Dawg in broad daylight in 2018, Mustafa released his debut project, When Smoke Rises, to universal acclaim. It was nominated for Canada’s lauded Polaris Prize and saw him collaborate with Jamie xx, James Blake and beyond. On it, he immortalises the friends he lost and tracks his rapidly gentrifying neighbourhood, all while becoming a singular new voice in the musical landscape.

“It explored one idea,” Mustafa tells Rolling Stone UK of his debut project, from his new home of Los Angeles. Many called it his debut album, but he never gave it that categorisation himself. “People also try and preserve this ‘arrival’ with a debut album for so many years,” he says. “It’s ridiculous sometimes, but people should identify their record in whatever way they feel will draw the most amount of attention to it because records take a great deal of sacrifice to make.”

If When Smoke Rises explored “one idea and one layer of grief that I was feeling”, his astonishing upcoming debut album is, in Mustafa’s words, “an amalgamation of my actual life and all its flaws and joy and cowardice and freedom and faith.

“They say your debut album takes your entire life,” he posits. “I don’t think my debut EP took my entire life, but it took the lives of others. This one took the life that I lived.”

Dunya, an album in the making for Mustafa’s entire life, marks the arrival of a generational artist. On it, he ponders childhood friendships, his Muslim faith, the chasms that war and conflict can create between people, the friends he lost in Regent Park and beyond, and discusses how to move forwards with so much pain in your rear-view mirror.

“There’s an incompletion in how we see ourselves and what we could have done,” Mustafa says of reflecting on the stories that formed the album’s narrative arc. “We see the love that we weren’t afforded, or that we could have given. There’s something about time that completes the memory, so when I look back at it, it feels perfect, feels full. This album feels like my own because it informs me. There’s nothing of it that was meant to be any other way.”

Stories from across Mustafa’s life pepper the album, most strikingly on ‘SNL’ (standing for ‘street n***a lullaby’). “I think I wanna be a good guy / But good guys die first,” he sings softly on the gorgeous track, before remembering “yelling ‘gang gang gang’ in my room” while his friend “sprayed me with perfume”. Elsewhere, ‘I’ll Go Anywhere’ sees him eulogise his brother Mohamed, who was murdered in 2023, and laments being unable to notice good things in the moment on ‘Beauty, End’.

Another pertinent and devastating highlight of the album is the track ‘Gaza is Calling’, written back in 2020. It tells the story of Mustafa’s Palestinian childhood friend from Toronto, and how the ongoing conflict in Gaza tore their friendship apart. “Every time I say your name / There’s a wall that’s in the way,” he sings on a song whose message is even more potent while Israel’s current war on Gaza rages on.

“There’s nothing I can do to properly communicate with someone misconstruing it, but to remind everyone I wrote it in 2020,” he says. He calls the song “an exploration of a deep love that I had for someone who lived in the hood”, adding, “He came from Gaza and had West Coast braids and a bottom row of grills. He found himself immersed in hood culture. I think there was something about the fastness and the pace of it that made him feel like he was back in Gaza. We sat among each other, became best friends, but his life in Gaza separated us. It got too hectic. It was not manageable. It was not sustainable.”

To promote the song, Mustafa shot a video in New York City with Palestinian model Bella Hadid. The video sees Hadid “explore this euphoric relationship” with 15-year-old Palestinian rapper Abdul, and intersperses shots of New York with refugee camps in the Middle East and Palestinian children. “It’s so, so gratifying to watch,” Mustafa smiles of the creation.

These deeply personal stories are fleshed out with the singer’s frequent musical partner Simon Hessmann and a varied and impressive list of collaborators. The National’s Aaron Dessner is behind the desk for much of the album, with artists including Clairo and electronic wizard Nicolas Jaar also credited. Mustafa calls the latter “really enchanting. Still today I’m in deep awe of him — I’ve never met anyone like him.”

The album’s most striking link-up comes on ‘I’ll Do Anything’, which features a stunning vocal turn from Rosalía, an artist who feels akin to Mustafa in how she melts cultures and sounds together in ways previously unseen. “There’s both a rhythmic and spiritual alignment between the music she makes and the music that has left me,” he says of the Spanish singer. “She is the last artist I know that has created a universe that was not there before she was. Her understanding of rhythm allowed for something that I didn’t even believe was possible.”

Maybe the most striking element of Dunya is how Mustafa’s stories are presented. With chief influences including Joni Mitchell and Big Thief’s Adrianne Lenker, he makes pristine folk music sparse in its instrumentation but overflowing in its beauty. On first single and opening track ‘Name of God’, he interrogates the reasons behind others using his faith against him, all set against the backdrop of a sweet and sprightly acoustic guitar line.

While he dives into the great American songbook frequently, he also honours his Middle Eastern heritage through the use of the Egyptian oud and other instruments from the region. It’s most apparent on ‘Imaan’, a dramatic and beautiful highlight described by Mustafa as a love song between “two Muslims journeying through their love of borderless Western ideology”. Elsewhere, he reflects the sparse acoustic beauty of Sufjan Stevens on the delicate ‘What Good is a Heart’ and incorporates the two sides of his identity and heritage into the music seamlessly.

“It was nearly impossible to look at these Arabian strings and the oud, with such an audacious presence, and these American folk chords that are more subtle in nature, and these drum patterns that remind me of the hood, and find a space where they all meet without compromising one another,” says Mustafa.

“Trial and error is one of the most effective methods of expansion,” he adds. “But there’s a divinity to the process, and I’d like to believe that I was engaging with these stories with a devotional quality. I was looking [at] and writing these stories in such a way that things were arriving to me as a result of that virtue and that space that I was leaving open. It was part-miracle, part-trial.”

With his debut album, Mustafa will by rights enter the canon of great folk singers, but it’s a space historically unwelcoming to Black and Muslim voices, something the singer has reckoned with and hopes to be part of changing. “There are definitely a great deal of white people in this space, and I think rightfully so,” he says, adding that these voices are “making such profound strides in American folk music.

“Folk music has been the music that has informed my understanding of myself and what I believe in since I was young,” he reflects. “I feel very fortunate that I can now be a person writing that music.” He pauses and smiles. “Isn’t that crazy?”

Mustafa’s personal breakthrough regarding his lineage in the genre came when he was able to spend time with the great Cat Stevens, which he describes as “a fuel that I needed to continue navigating the larger world”. He says, “I quickly realised after meeting him that I was looking for community, but that I needed to find that community in myself. I realised I was always going to be removed from the referential narrative of people in this [folk] world that I love so much.

“I’m still a n***a from the trenches, still Muslim. I’m still fighting every kind of trial and dealing with a world of violence that a lot of these people never even have a doorway to understanding. I have to be confident in the thing that I do, because no matter, I’m worlds apart from so many others. I have to conduct myself in a way that allows me to believe in the thing that I’m seeing, because it’s easy to waver when you don’t have a point of reference for what you’re becoming.”

Through this amalgamation of sounds, the open-hearted and inquisitive stories that the songs tell, and the voracity with which he spreads his message, Mustafa has the chance to become a trailblazer for Black and Muslim voices in these spaces, as well as an outstanding artist in his own right. The idea sits somewhat uncomfortably with him though.

“I realised I was always going to be removed from the referential narrative of people in this [folk] world that I love so much. I’m still a n***a from the trenches, still Muslim”

He says he doesn’t want to be held up as an icon because “I feel like I’ve made such grave mistakes,” adding, “I know Tupac has already said this, probably far better than I have, but if I’m able to create space for another person to be the reference point, that would be really transformative for me. In terms of myself, I don’t know. I have a tricky relationship with idolisation and symbolism and authorship. I don’t know what it is that I’m actually deserving of, and I won’t know until I’m at the end of my days and I can reflect on the life that I’ve lived, what I’ve actually given and what I’ve actually taken, and whether it was a fair transaction.”

A lot of Dunya lives in these liminal spaces between past and present, question and answer, seeing life and memory as something ever changing. One absolute truth for Mustafa arrives on the song ‘Leaving Toronto’. “It has nothing left to give me,” he says of his home city, remembering “driving five hours to cry in Montreal”.

“Toronto was a hellscape,” he reflects now. “I’ve buried so many people that I loved over there. I don’t feel a sense of community there. I feel so disconnected from the city, and it has to take accountability for its dead and its callousness.”

He describes the song — a highlight on an album full of devastating truths and brilliant beauty — as “an infinite return to home”, adding, “It’s a song about my isolation from friendship, love and care. In every space I walked in, I felt surveilled. Me leaving Toronto was a rejection of that surveillance. It was freedom.”

Taken from the August/September issue of Rolling Stone UK – you can buy it here now.