Halsey: no boundaries

After two years of battling life-changing illnesses, Ashley Frangipane emerged from the other side with an album she thought could be her last: ‘The Great Impersonator’. The 30-year-old singer tells the whole story of motherhood, separations, treatments, recovery, and meeting their new partner. What happens when an artist who made their name through oversharing online decides to stop talking? Halsey isn’t sure yet

By Hannah Ewens

If God keeps a scoreboard of the challenges she sends her strongest followers, Halsey’s experience from February to March 2023 would rank above most other pop stars.

The singer knew she was approaching the Saturn Return, an astrological transit that forces maturation by way of life lessons. But while some people report a breakup or job loss, Halsey had a triad of dour experiences. She was dropped from their long-time label, Capitol (though at the time the split was reported by the Halsey camp as their decision), had just started treatment for a newly diagnosed leukaemia while waiting to treat a secondary diagnosis for lupus, and separated from the father of their baby son. To put it literally, they didn’t know if they would survive.

“I was like, ‘Fucking Jesus, I don’t even know if this is astrology anymore. This feels like I’ve been cursed,’” says the 30-year-old – who uses both she/they pronouns – when we meet for dinner ahead of their Rolling Stone UK digital cover shoot. “I started looking online for a witch to help me. I thought I’d been hexed or something.” She meets my gaze knowingly, anticipating my journalistic excitement about the witch she hired, then pauses and tempers my enthusiasm: “I did not hire an online witch for the record.”

Their sickness, when it came, was insidious. She had long suspected an overarching serious condition because she had multiple smaller diagnoses frequently attached to something else. Or as she puts it, “I had four table legs and no tabletop.” Once she had their first son Ender, their inability to be a present mother with him revealed that something was wrong. She was in severe pain and weight was disappearing from their frame. Baby Ender was too heavy to carry. She went looking for answers from different doctors: one said she had lupus. When another doctor returned with a leukaemia diagnosis, she assured him it was lupus. No, the doctor said, you have leukaemia, too.

“I think the shittiest thing that happens when you have a significant illness is that you just lose your personality,” she says, and adds with characteristic humour: “Your body’s like, ‘I can’t burn energy on that. I don’t have enough in the bank for that, not enough in the tank.’”

In more than a physical sense, she was dealing with illness alone. Friends she thought would always be there disappeared when she was no longer fun. Part of Halsey wasn’t surprised when their family of three broke up. “I never pictured myself as a happy family. Whenever I would fantasise about being a mum, it was just me and my kid. And not in a defensive ‘I don’t trust people’ way, that was just how it would show up,” she explains. “It was interesting when we tried to make a family unit work for a while. As soon as I got used to it and I liked it, I had the rug pulled out from underneath me. I became a single mum. I guess I always knew subconsciously.”

The decision was made to stop doing press and keep their personal life completely private. “That was my one big boundary at that time,” she says, knowing that at a later date, she’d inevitably speak about their illness. Both of their illnesses are chronic and still stand, though they’re essentially in remission. In the interest of not being in a constant state of panic, she calls the leukaemia by the name lymphoproliferative disorder when it’s not active.

It was a welcome stroke of luck that she had already temporarily retreated from the public eye prior to this point because she felt overexposed – and she had been extremely visible for an entire career. Their website once accurately introduced the singer: “I am Halsey. I will never be anything but honest. I write songs about sex and being sad.” First, she was tipped as an edgy pop artist helping to define millennial genre-blending alternative-pop, along with contemporaries like The Weeknd and Lorde. Then she had a slew of global radio hits. Next, she became a viral spokesperson for endometriosis and women’s health issues. The same New Jersey sarcasm, charisma and vulnerability that attracted their fanbase also made Halsey ideal tabloid material, particularly for romantic escapades with other famous musicians.

Halsey began their career as a teenage Tumblr microcelebrity – the curation site where users repurpose film stills, poetry, and music videos – which makes sense when you examine their music. She adorns projects with millennial pop culture references like they’re statement jewellery, not trying to obscure or minimise their sources: Jennifer’s Body, Brand New, Shania Twain, Britney Spears. What makes a great Tumblr page is a singular curatorial voice and the one element of Halsey’s work that critics generally agree on is that she provides that in their records and in person. She’s self-possessed, funny and able to talk about their interiority with intense lucidity.

Their fanbase feels that she articulates the dire and chaotic fantasies of young womanhood. As she tells me while miming grabbing someone’s face, “I don’t want fans that are passersby, unfortunately. I’m the same way as an artist as I am as a person. I demand a lot of people emotionally and we gotta be fucking locked in as human beings, or I don’t want it.” Despite their role as a feminist activist, their music has never provided feminist anthems. “All of my songs are just me trying to figure out what’s wrong with me all of the time. They’re quite self-involved,” she says.

Without knowing what was wrong with Halsey, a loud minority of fans began to assume the worst. “Most of my peers’ fans jump through physics-defying undeniable hoops to defend their artists. My kids, if something happens to me, 99 per cent of the time, they’re like, ‘What’d you do, Halsey?’” she laughs. They assumed she was the one to blame for the breakup. They argued about whether the weight loss was down to drug use. “Your first thought isn’t maybe it’s a health condition thing, it’s that I’m doing drugs with a one-year-old baby. Why is your username HalseyBadlandsPowerLove? Why are you a fan of a person you think would blow up their life in that way and take no responsibility for it? It was shocking.”

This discourse made Halsey reconsider their attitude towards being a public figure. At one point in our conversation, she says, “I don’t want anyone to know anything about me.”

“I think the shittiest thing that happens when you have a significant illness is that you just lose your personality”

Tonight, we’re meeting at their all-white hotel suite in the regal Rosewood hotel in Holborn, London, to talk about the new Halsey album, their fifth, The Great Impersonator. It’s a couple of nights ahead of a secret show she’s playing to fans at the venue KOKO and she emerges with short red hair and in a band shirt and jeans. She is slight and preternaturally beautiful, like an elvish princess who traded a peaceful life in Rivendell for a job at a dive bar. Their son Ender has just been put to bed, and she’s monitoring his sleep on an iPhone.

Motherhood has always been their ultimate dream. After experiencing a miscarriage at 20, adult life has revolved around achieving optimal health for conception. This journey involved rigorous adjustments – supplements, cutting-edge treatments – but mostly, it boiled down to setting boundaries. She recalls a pivotal conversation with their gynaecologist, asking, “If I want to have a baby, do I have to quit my job?” The doctor explained that it might be possible to juggle both, but only if she meticulously managed the stress in their life.

Halsey’s late teens and twenties had been marked by toxic relationships of all kinds. It may sound like magical thinking, but they felt that this was taking a toll on their body. “I was a kid who came from nothing, and I just didn’t know how to say no to people because I had survivor’s guilt and wanted to bring everyone with me,” she reflects. In those early years of their career, she supported a revolving door of friends and family, financially backing 15 to 20 people.

The absence of boundaries also played out in their romantic entanglements, which served as the backdrop for many of their songs. “In hindsight, I have always wanted to be a mum more than anything because as much as I love my career, and no matter how intoxicatingly captive some of the relationships I’ve been in were, any time the conversation came up of, ‘You need to not do this, or we’re not getting closer to you being able to have a baby,’ that was all I needed to hear. Nothing else could get through to me but that.”

There were two distinct Halseys: the fierce, hard-nosed entrepreneur and pop star, and the real-life woman. The latter had to fake the former to achieve their dreams. “For a very long time, I was personally an absolute doormat. It’s different from the persona my music evokes or how I act in business. I was doing a lot of that to overcompensate, but I harboured a lot of resentment about it.”

When COVID-19 hit, she seized the moment to focus on conception, viewing the pandemic-induced hiatus as an opportunity to prioritise their health and cut ties with draining relationships. “I made myself very exceptionally lonely right before I had a baby, which was a terrible idea. I don’t regret doing it, though,” she admits. Motherhood has been “paranormally revelatory”, she states, like finally putting on the correct prescription glasses. It’s a profound shift – life before Ender and after Ender.

“For a very long time, I was personally an absolute doormat”

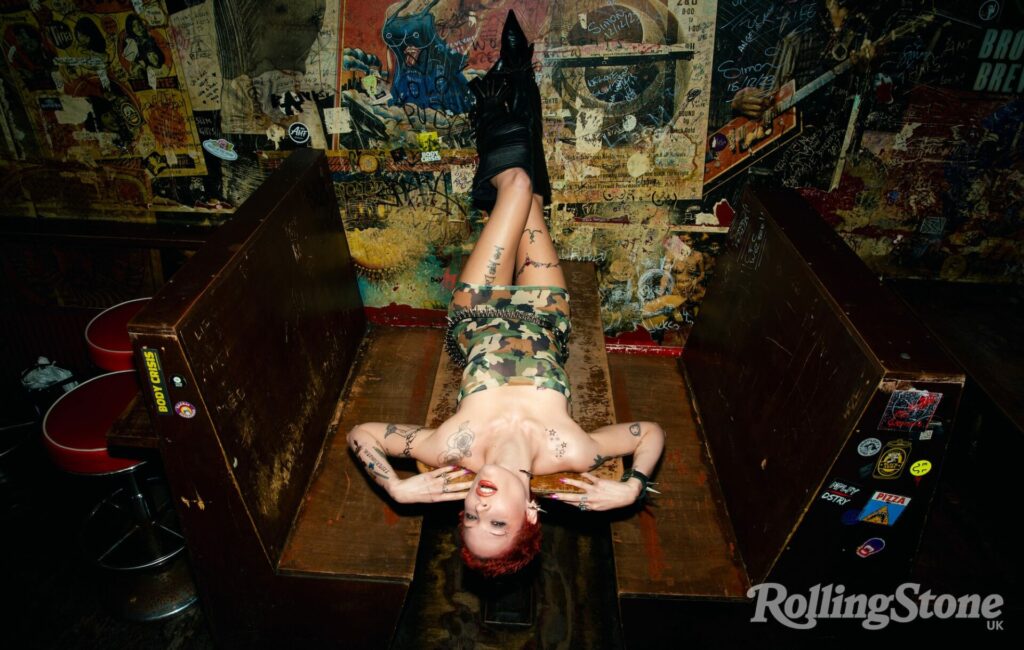

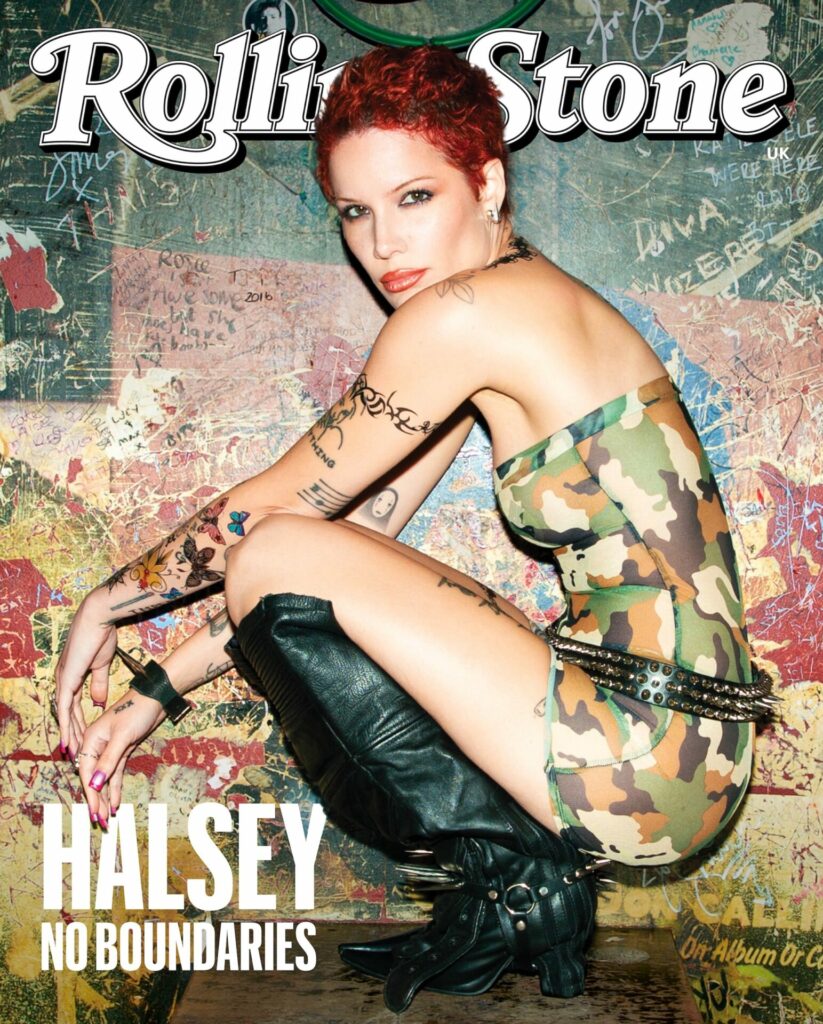

The following afternoon I arrive at the photo shoot for this profile at Slim Jims Liquor Store, an American-themed rock’n’roll bar in north London. Halsey is preoccupied. She has chosen to be shot in white lace underwear on top of the bar with restraints binding their hands behind their back. I don’t make out what she yells at me, only that she’s having fun. “Sorry, I couldn’t say hi properly – my hands were a little tied,” she tells me minutes later without missing a beat, and then, with help, gets hermetically sealed into a rubber dress and stripper heels.

As she’s preparing to give a video interview to the camera – trying to decide how to sit or stand while mummified by latex – she explains that after being pregnant and ill, she grappled with the feeling that their body didn’t belong to them. Now is a time that she can reclaim that body by wearing what she wants. Good for you, everyone on set echoes back.

Later, she elaborates on their relationship with their body during their illness, describing it as mechanical – washing and dressing as a means to cope rather than care. “I wasn’t connected to my body,” reflects Halsey. “At the time, that was a good thing, but you can accept your body too much. I took it too far and ended up disassociating. There’s a difference between accepting your body and ignoring it.” Rediscovering their personal style has become part of this reconnection. They shunned baggy clothes, which reminded them of the sweats she wore while sick. In the promotional run for the new album’s lead single ‘Lucky’, she donned Y2K-inspired outfits that felt cute but ultimately left them feeling out of sorts – ironic for an album aptly named The Great Impersonator.

With The Great Impersonator, Halsey sees themself through a kaleidoscope of identities, slipping into various personas inspired by pop culture from the 70s to the present. This type of play-acting feels familiar for an artist who has spent their career embodying and critiquing feminine archetypes. She’s been The Lover, their romantic life a public saga of highs and lows. She crafted a concept album inspired by Baz Luhrmann’s reimagining of Romeo and Juliet, and she’s navigated the territory of The Madonna and The Whore, famously gracing the cover of their fourth album, If I Can’t Have Love, I Want Power, with a provocative image to challenge our mundane ideas about mothers.

Perhaps most notably she has been the Manic Pixie Dream Girl – the trope of a whimsical, attractive, often mentally ill woman – the unguarded artist who is open about having bipolar disorder and being bisexual. On their third album Manic, which she made while on a manic upswing, she even included a track called ‘Clementine’, a reference to the ultimate hurricane of a MPDG from Eternal Sunshine of a Spotless Mind, on whom Halsey once said she based their whole personality.

The Great Impersonator was created over two years during their illness, a time when touring was out of the question, and their music career felt tenuous at best. It was made knowing that it might be the last album she ever made. For the first time, Halsey confronted mortality, and whenever she found a moment – whether Ender was asleep or preoccupied – she attended to writing a song. They considered themes like motherhood, postpartum depression, growing up, and what she refers to as a “spiritual reckoning”. It was during these dark moments that she pondered the existence of God: “I spent so much time wondering why, if God was real, I was sick. But then I’d look at my son and realise that God must be real.”

During the writing and recording process, with lo-fi producer and musician Alex G and Michael Uzowuru, she realised how many restrictive self-imposed limitations she had placed on their work through the conditioning of the music industry: fear over a six-minute song when trained to create three-minute songs for radio, concern over getting their vocal takes perfect. As a rebuttal, some of these new songs she goes as far as to call “purposefully bad”.

Though that may seem harsh, the tracks we preview do sound like demos. The influences are, as ever, palpable, echoing the early 2000s pop landscape: the energy of Avril Lavigne’s debut, shades of Michelle Branch and Vanessa Carlton, and a celebratory nod to Bruce Springsteen, the king of New Jersey. Each song serves as a memory – a sonic scrapbook – both for Halsey and their listeners. She tosses out references like confetti: Portishead, Regina Spektor, The Postal Service, Massive Attack and Radiohead. Most strikingly, the album feels infused with gratitude.

Among the standout tracks is a breezy covert breakup song, ‘I Never Loved You’, written in the aftermath of a breakout. “I’ve written so many breakup songs that I had to reinvent new ways to do it,” she laughs, comparing it to their track about G-Eazy, ‘You Should Be Sad’, where she expresses, “I’m glad I never had a baby with you.” “How do I, as a mature adult with a child, write a breakup song that’s not just ‘Fuck you, you fucking loser?’”

The album’s title emerged from a poignant conversation with their manager and best friend, Anthony Li, during the height of illness. Halsey realised how ironic it was that they’re an artist who prides themselves on being honest and was now keeping the biggest secret from their audience. When she had to be seen, she put on wigs and heavy makeup. “There was already this magic trick brewing subconsciously in a sleight of hand of ‘don’t notice how sick I am.’ I was like a magician,” she says conspiratorially. “I felt like a professional Halsey impersonator.”

The title track speaks to this duality: “It’s about the irony of dying with so many people who feel like they know you, only for them to realise they didn’t at all after you’re gone,” she says, pausing for a moment. “So, a super chill song for a pop album.” Then, with a dry laugh, she adds, “I’m sure you can tell why this was not a summer album.”

“I felt like a professional Halsey impersonator”

We’re in the hotel room, Diptyque candles burning down, and sushi platters abandoned, talking about the album’s third single, ‘Lonely Is the Muse’. It’s a heavy industrial-pop song with rock vocals about twisted dynamics she’s experienced as a female artist. “Where do I go in the process / When I’m just an apparatus / I’ve inspired platinum records / I’ve earned platinum airline status,” she sings on the recording.

Halsey tells me a story about when she hosted a raucous party at their house. It was 3am and she was splashing around in the pool in underwear, drenched and carefree, surrounded by friends. But the revelry was short-lived when the police arrived to shut it down after complaints of noise. In a twist of fate that felt almost scripted, the officers presented a deal: she wouldn’t get in trouble if she agreed to take a photo with them. So there she stood, soaking wet and vulnerable in a bra, grinning alongside two police officers. At the time, she had found it a hilarious relief – she evaded trouble. “It wasn’t until a couple of years later that I was like, ‘Damn, those cops just have a picture of me half naked on their phone,’” she tells me. “I’m sure it comes out in bars. Ah, don’t love that.”

“All those little versions of me that are out on their little side quests, floating around the world – I wish I could bring you back home so that you weren’t out there going through that,” she continues. “That picture on that phone, that nude on someone’s phone, that Polaroid photo, all those little versions of me in that intimate space whether consenting or not, that are out in the world that people were using for whatever, I wish I could call them back. That’s a really lonely feeling.”

It’s a sad and new part of modern relationships, I offer. It’s humiliating, she agrees, and tells me that a female friend recently had a breakup with her boyfriend and during the separation, made him unlock his phone and delete every nude photograph and video he had of her, while she watched. It speaks volumes about my own boundaries and lack of self-respect, I say, that I have historically wanted exes to keep that content, something to come across in the future weeks and months.

“No, I totally get it, I’m the same fucking way,” says Halsey, adding that ‘Lonely Is the Muse’ is partially about people-pleasing. “I’ve always wanted to be the Cool Girl. And asking someone to delete all your nudes is not very Cool Girl of you, even in the breakup. I’m different now, but that song is about a decade and a half of that.”

It doesn’t matter how successful you are as an artist, the song suggests that you can still be reduced to a girl in a bra, a story. It is about exactly this sentiment: “I’m giving so much of myself away, for fuck’s sake.”

It’s also about being considered a muse when you’re providing more than just “inspiration”. “I stopped talking to people I dated about their work. One of my love languages is helping…” she says and tails off. I can see where this is going, I reply. She would help exes with songs or projects that would go on to be big successes. She has come up with a music video concept for a Halsey release and they’ve ripped it off before she’s had a chance to make it.

Sometimes exes would write about Halsey directly, but it wasn’t the act of men writing about them itself that was annoying. That’d be hypocritical since all their own work is autobiographical and thinly veiled. “I really hate when it happens and it’s a person who refuses to admit that you’re dope but then they’re stealing from you or they’re referencing you or they’re writing about you. That always lights a little juvenile fire in my belly,” she says.

This creative murkiness extends into their professional life, too. Halsey details the frustrating moments of being uncredited for contributions: the times she crafts plans for brands, only to see the marketing executive take credit, or when she co-directs a music video but gets overshadowed because the director wouldn’t join unless they received sole credit. There is the ambient sense that though she brought Trent Reznor and Atticus Ross of Nine Inch Nails in to produce and help work on the most recent – and most critically praised – Halsey album, they are the ones that made it good. To that she thinks, “Is everyone OK? You think that two rock dads wrote my female rage album about the horrors of being pregnant and accepting suburbia?”

Given her resentment around these experiences, it was a surprise to Halsey when she met the person that would become their fiancé – another creative! – the actor and musician, Avan Jogia, on a trip to Europe. “I’d said no more fucking entertainers,” she laughs. “I’m gonna find someone and it’s either gonna be the most beautiful paediatric nurse you’ve ever seen in your life or a guy who works in accounting and then when I met Avan, I was like, ‘Fuck. I’m screwed.’”

For the first couple of months, Halsey wondered if he was a masochist for dating a sick single mother, sceptical until she met his “wonderful” parents. “I don’t know where I’d be without him. He’s been instrumental in my healing, my recovery, my self-concept,” she shares. “Not just from being sick, but I was still grappling with postpartum depression. I didn’t know how to be a person separate from being a mum. I didn’t feel very autonomous in my body. But he really made me want to try because I liked him so much. It motivated me to work on myself at a time when I desperately needed to.”

She’s since learned that Jogia is a healthy person who is exceptional at setting boundaries. “I watch him set a boundary without compromising his niceness and I’m like, ‘Oh, that’s interesting math, you can do that? Noted, writing that down.’” She pauses to think and says, “I don’t know how to do that; I just know how to consume. That’s all I know how to do. I’m working on it though… Like I said, I got more confrontational in a positive way.”

Their manager, Anthony Li, is in the room at this point. Li essentially discovered Halsey when she was just a teenager on a night out, encouraging them to be a singer as a means of getting their written poetry out there. He jumps in to say that she’s working on boundaries and absolutely getting better at them. “Do you fully believe that?” she asks. I do, says Li, “I’m not saying you’re good at it but you’re growing in that department.” She nods quietly and seems to meditate on this apparent progress.

“I thought I was exempt from the arrested development thing,” she says, turning to me. “I saw that in a lot of my peers, where I was like, ‘Oh, you’re stuck at the age you were when you became famous – not me, though!’ But there are definitely parts of me that are still stuck at 18 or 19, and those were the parts that needed attention. The not setting boundaries, the people-pleasing.”

“If you do die, it’s things like this article that end up defining parts of your legacy”

Seeing Billie Eilish perform at Madison Square Garden when Eilish was just 18 made Halsey reflect on the fact that she was around the same age when she achieved that milestone. “You weren’t not a child star,” she acknowledges, though she admits watching Eilish felt a bit like being put out to pasture.

She does, however, wish that she still possessed some teenage qualities that have passed away: the overconfidence, the near-obnoxious belief in their art, and the insistence on following a gut feeling to the end. For the first two years of their career, she was “fucking locked in”, as emotionally connected with that rise as she says she demands personally of other people. Now she looks back on that period and can’t believe how much she believed in Halsey.

“What the fuck were you doing? Knowing what I know now, you should have been scared,” she says seriously. “The likelihood of that working out that way was very slim. Why were you so confident?” But then, she says, that younger Halsey appears in their mind to goad their older self with: well, it did all work out just as I’d planned.

Ten minutes later, she’ll set a boundary by telling me it’s time for the interview to end. Well, she doesn’t state it directly, but enacts it with their body language and by standing up and saying she has a bit of a headache. It’s not perfectly executed but I get the message.

When we reconnect over a remote call three weeks later, Halsey sounds both exhausted and serene. It’s clear she’s been running on fumes since that whirlwind stint in London. Three weeks of work is their limit now, compared to the months of back-to-back work she could manage before, pre-baby, pre-sickness. Now the album title and trailer have been announced, she’s been thinking a lot about what kind of artist she wants to be. What happens when a compulsive-discloser voice of a generation stops talking? It’s a transition that could leave some fans feeling adrift, and she worries they may be disappointed by their newfound reticence. “I’m never afraid to hold the microphone. I’ve just stopped taking it all the time… but if you give me the microphone, I’ll be honest,” she says with a smile.

After becoming more private, she’s since realised she has to return to a centre ground if she wants to have control over Halsey, the artist. “There are things about myself that I’ve been keeping to myself to protect my privacy, quote-unquote, but what I’ve done by accident instead is I’ve prevented my public persona from aligning accurately with who I am,” she explains. “And that was a really weird epiphany to have as an artist who’s prided themselves for so long on being authentic and an open book. I was like, ‘Oh, maybe I’m literally not, actually.’”

Before we end the call, I thank Halsey for the extra time she’s afforded me, and she thanks me back. She doesn’t do a lot of written press anymore, so our prerogatives are the same: for this profile to be great. “Not to be so dramatic, but I thought about this kind of stuff a lot when I was sick,” she says. “Because if you do die, it’s things like this article that end up defining parts of your legacy. You don’t want to take them that seriously when you’re doing them, or everyone would be in a state of panic every time they were doing an interview having that sort of existential thought – but I did think about it quite a bit. What would someone dig up and read about me? Without my ghost qualifying the whole thing, standing over their shoulder being like, ‘No, no, no, they got that part wrong.’”

Halsey features on the forthcoming 20th issue of Rolling Stone UK. You can pre-order it here. On sale November 28.

Photography by Sarah Pardini

Creative direction by Joseph Kocharian

Styling by Lyn Alyson

Assistant styling by Kelly Goldy-Brown and Annum Mohammed

Hair by Anthony Perez

Nails by Natalie Minerva