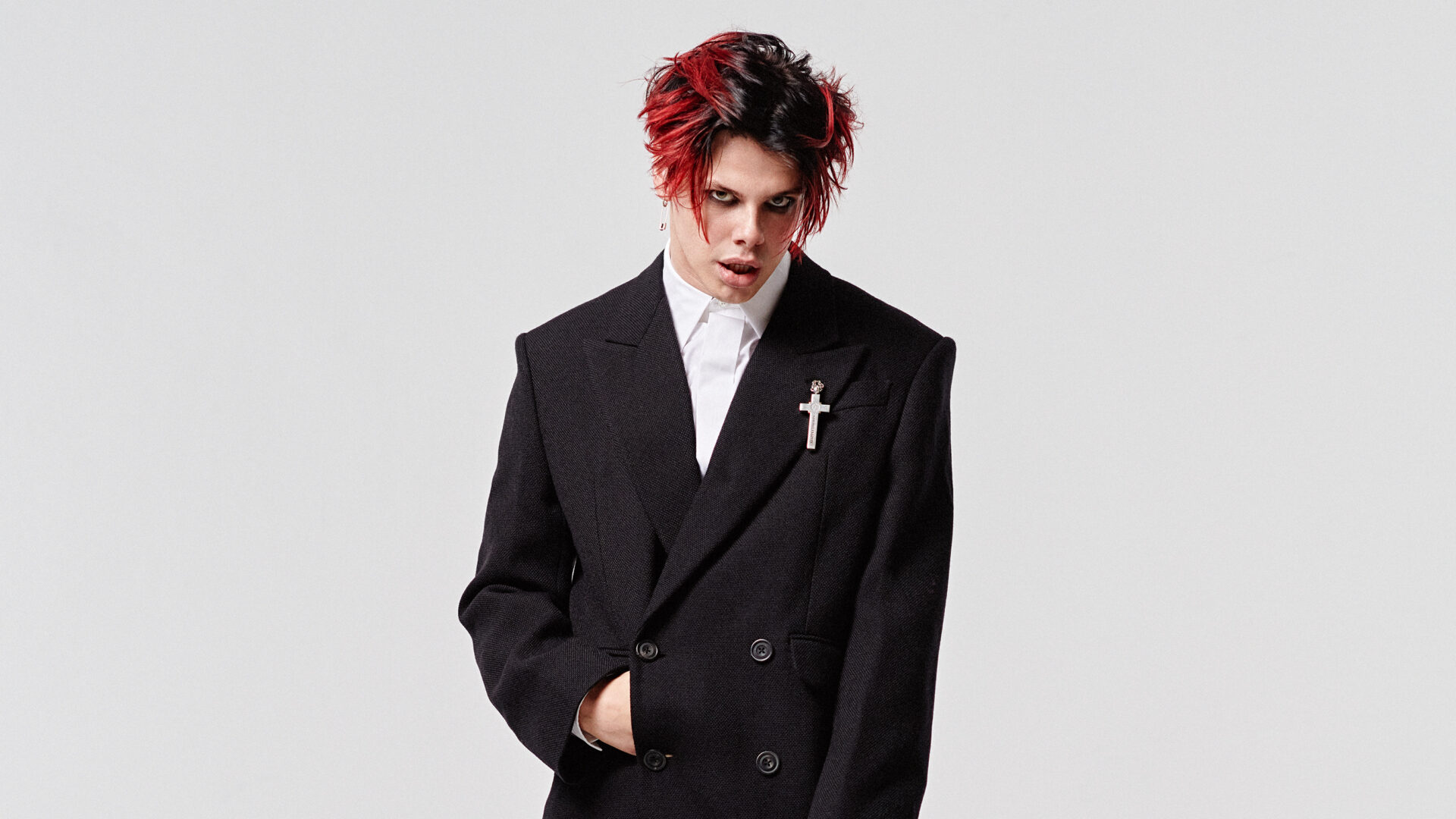

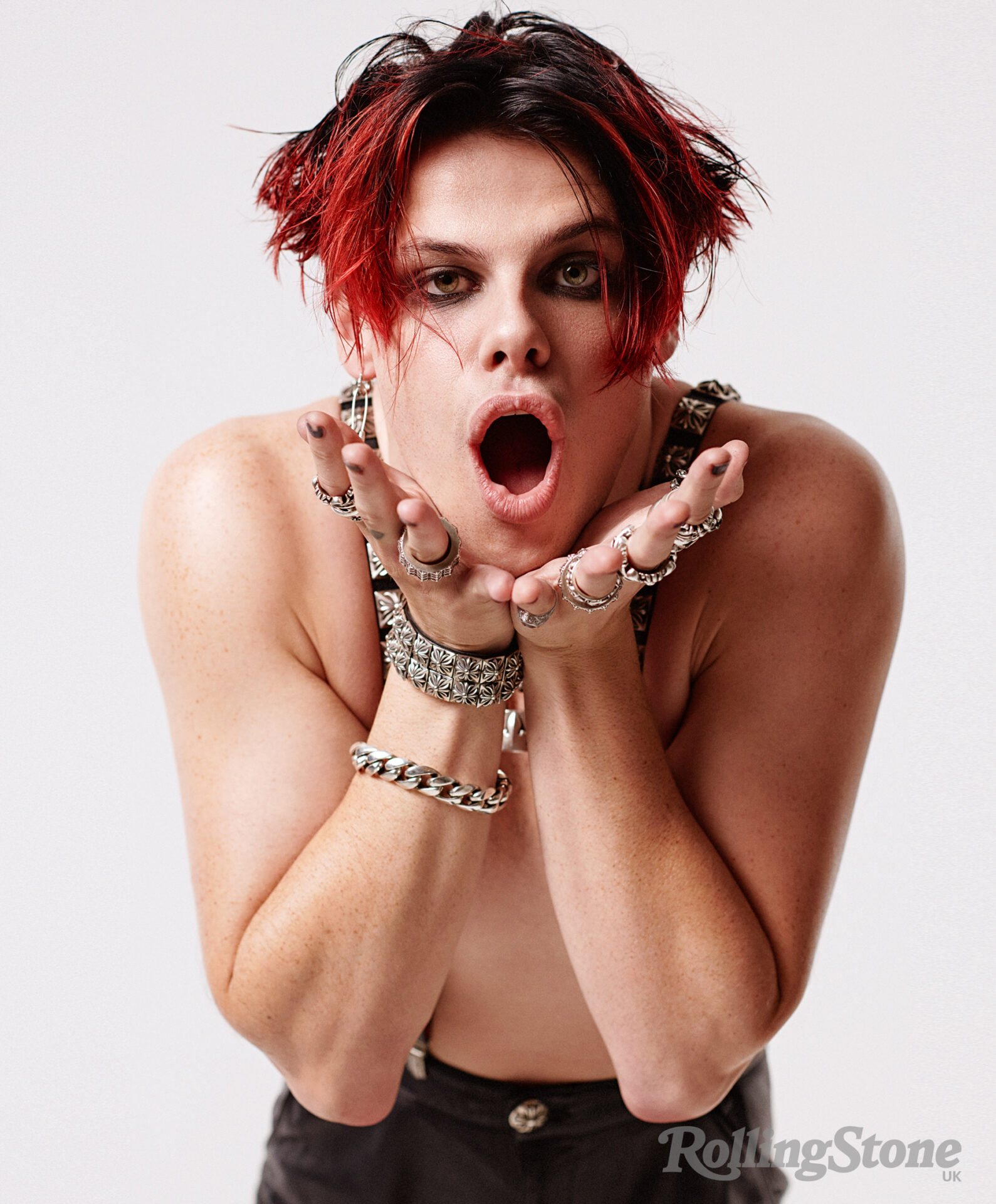

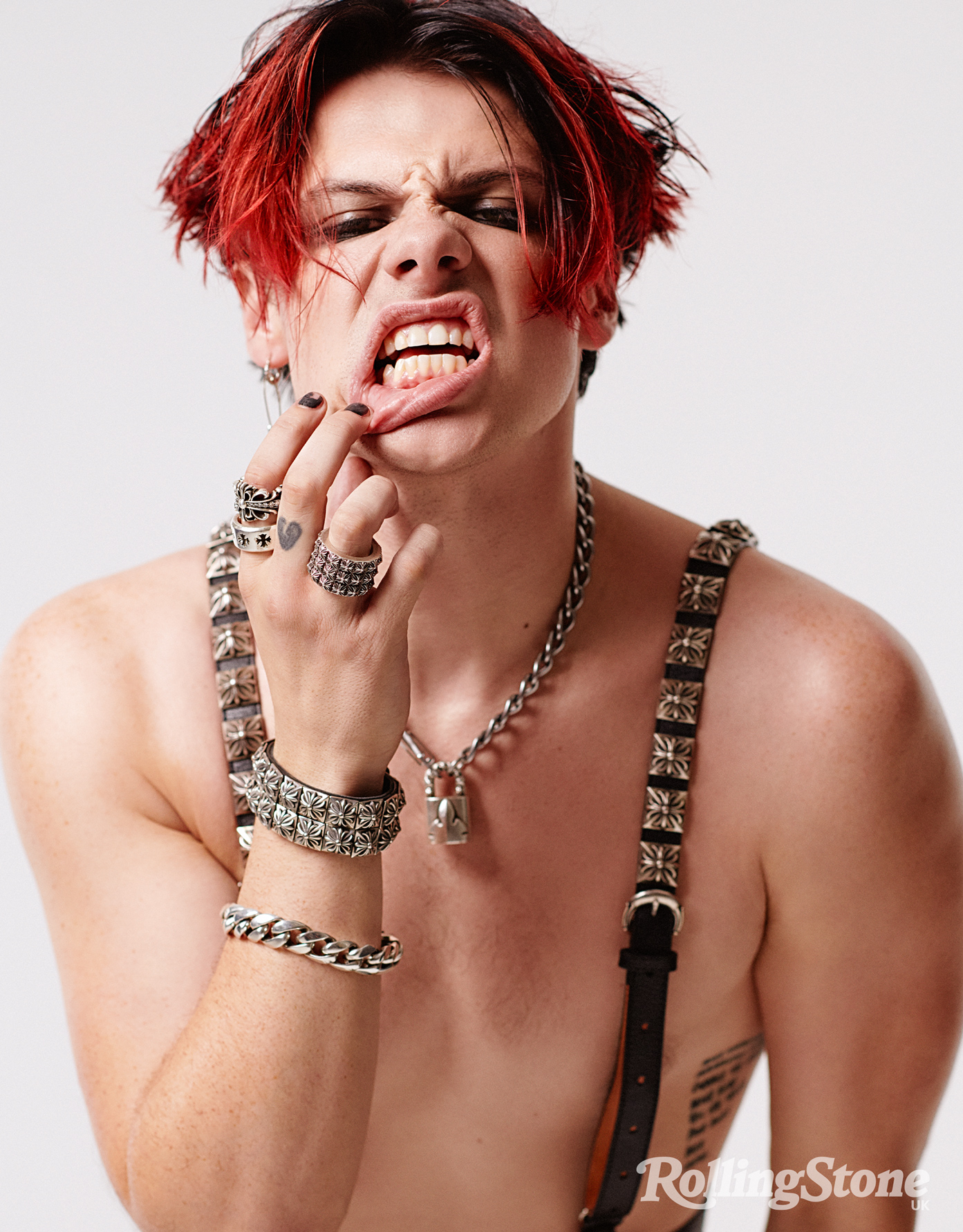

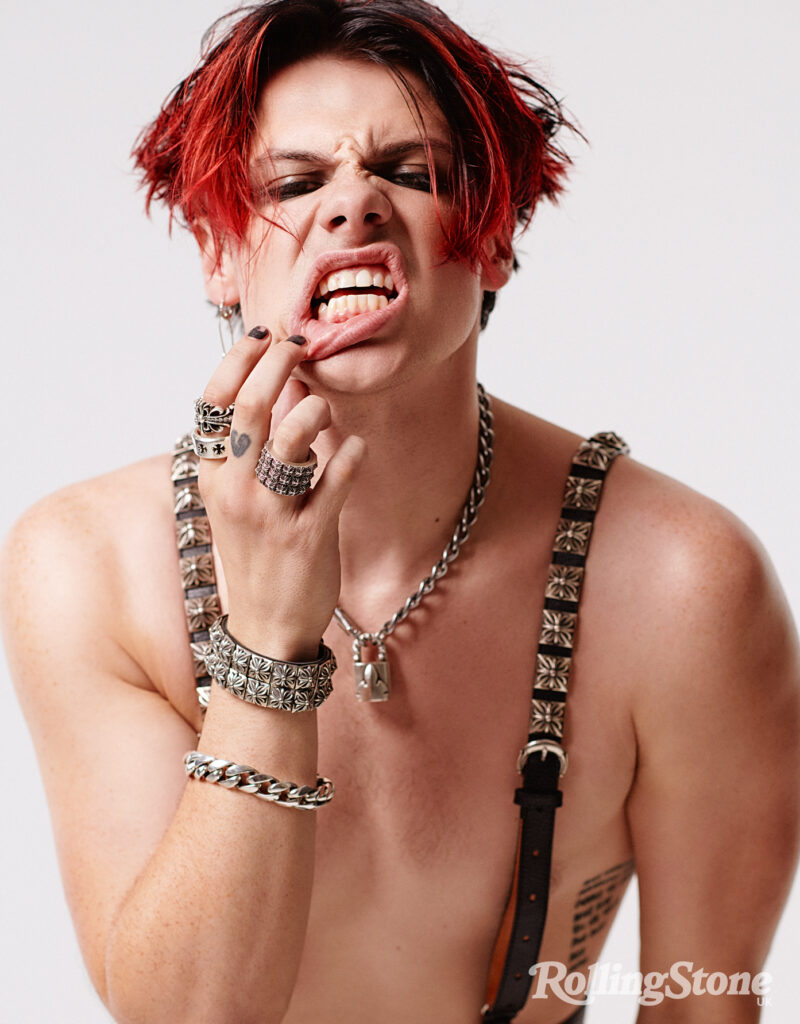

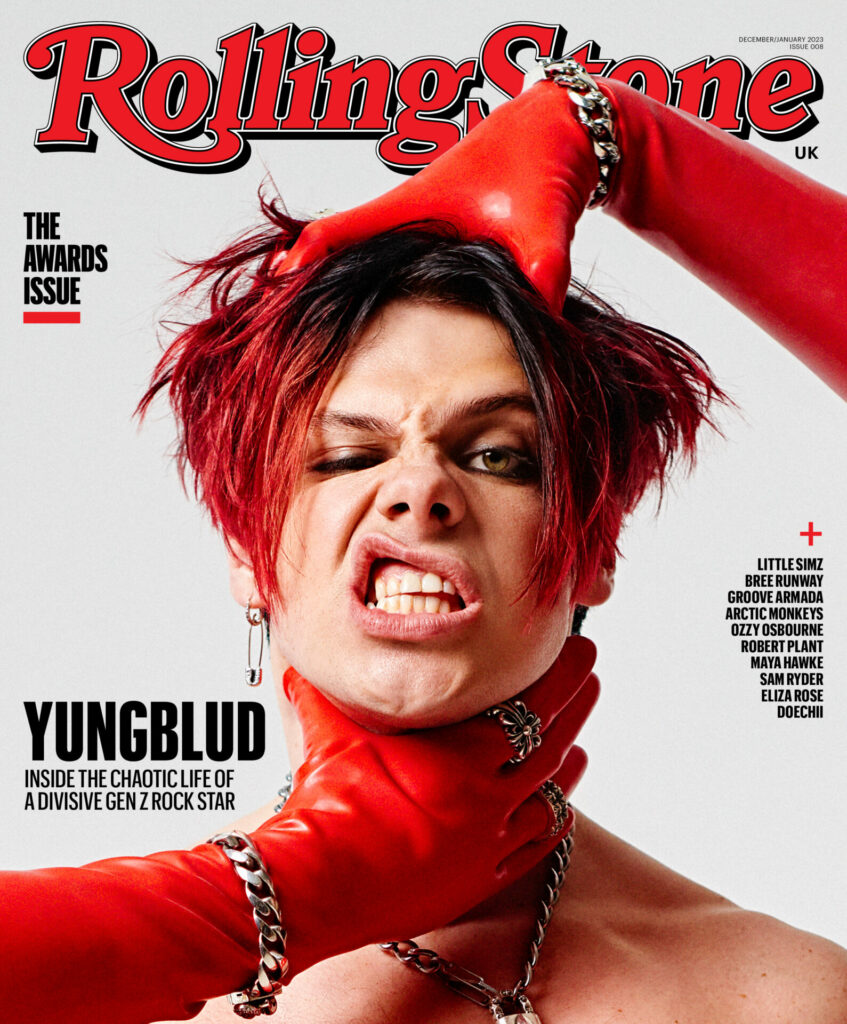

Yungblud: how to win fans and influence people

Love him or hate him, Yungblud exemplifies what it means to be a Gen Z rock star. Dominic Harrison harnessed an influencer model to rise to fame but in 2022 proved he’s well on the way to becoming a British pop culture icon. Rolling Stone UK goes on the road with our Artist of the Year to find out how he intends to use more than his high-energy persona to be taken seriously

By Hannah Ewens

While Dominic Harrison was unwinding with a pint in a bar in Portugal recently, a stray bloke from a stag do asked him if one of his mates could come over. Harrison, ever the people pleaser, said yes. The rest of the stag party went to bed drunk, but this friend came over and started drinking with the singer known to the world as Yungblud. “My wife is a big fan,” he told Harrison, “but I think you’re a bit of a dick.” Harrison entertained this man and his monologue because he is used to interactions like this — a portion of the general public finds his animated persona irritating and something about his relentless enthusiasm invites what essentially amounts to abuse. Strangers speak to him as though he’s a toddler or not really in the room. These scenarios in which Harrison plays unpaid therapist to his adversaries are why he must soon move from his home on Old Street, a siren call of a roundabout in London for people without respectful boundaries to gather: bankers, tourists and 20-somethings from Essex.

“I just don’t know why you’re always so fucking excited all the time, like on the telly,” the man informed Harrison. “I don’t believe it.”

“I told him: I’m on the fucking telly, of course I’m excited,” Harrison relays to me in his Yorkshire accent. “What would you do if you’re on the telly and radio?”

You’d probably crank your personality up to 11, stretch your face into a grin and amplify each word: Y’alright? I’m fucking Yungblud. It’s not an act, not really. The 25-year-old Harrison feels something close to mania to be living his dream. Ever since he was small, growing up in Doncaster with a dad and grandad who sold second-hand guitars to famous musicians, he wanted to be a performer. In his teens, he acted on Emmerdale and a Disney show. Since releasing his debut album on a major label in 2018, he has demonstrated a desire for the type of straightforward fame that can turn rock fans off, particularly anyone old enough to remember being able to make respectable money without befriending brands or becoming one yourself.

To say Yungblud has been a divisive presence in British pop culture over the past five years would be putting it more mildly than anything Harrison has said in his life. For all the hostility, there is the adoration, the fans who run up to him to overshare and worship. “Imagine walking down the street and everyone loves you or thinks you’re a fucking c*nt and hates you,” he says. “There’s hatred for you. You sign up for it and then it happens and you’re like… holy shit.”

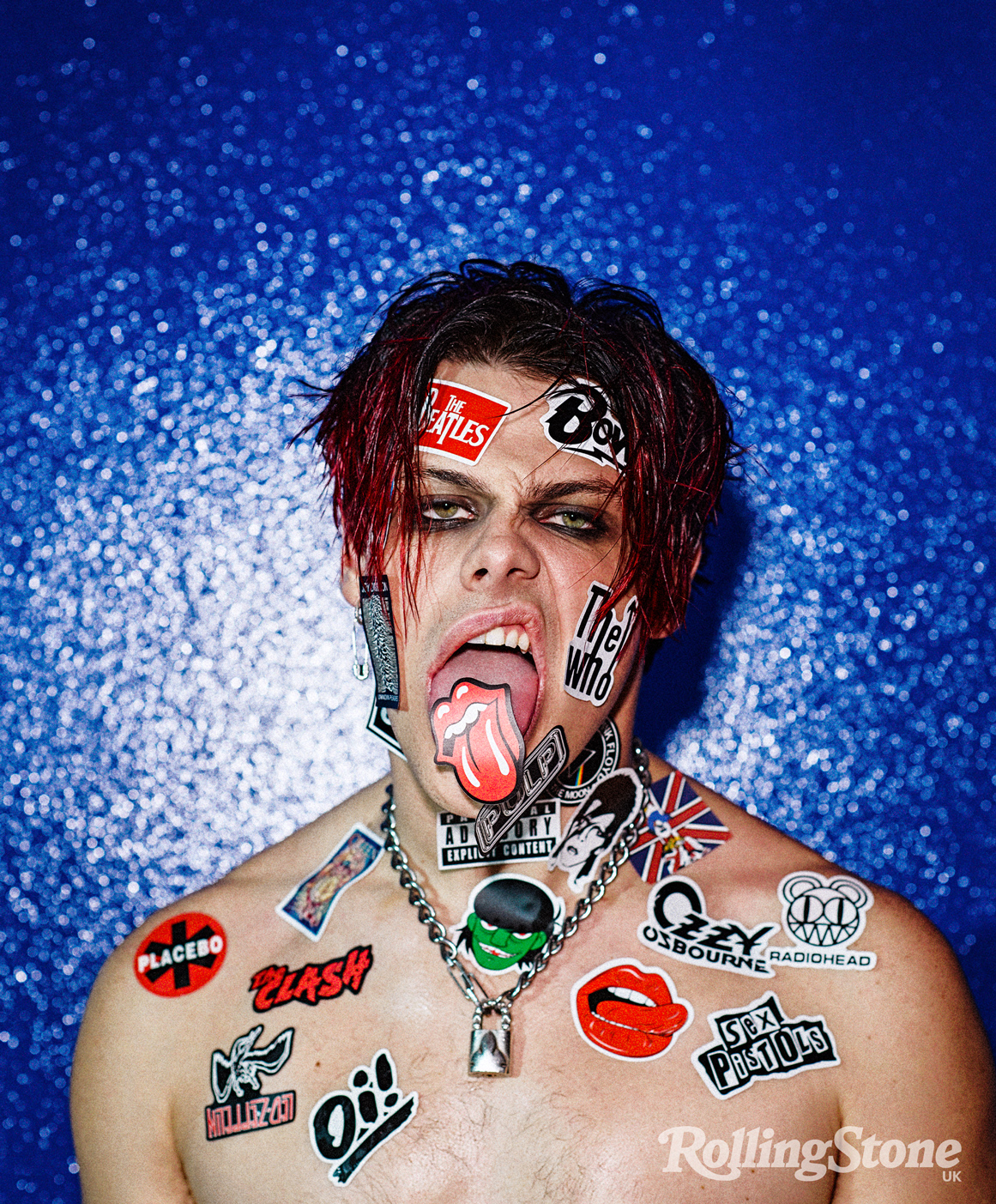

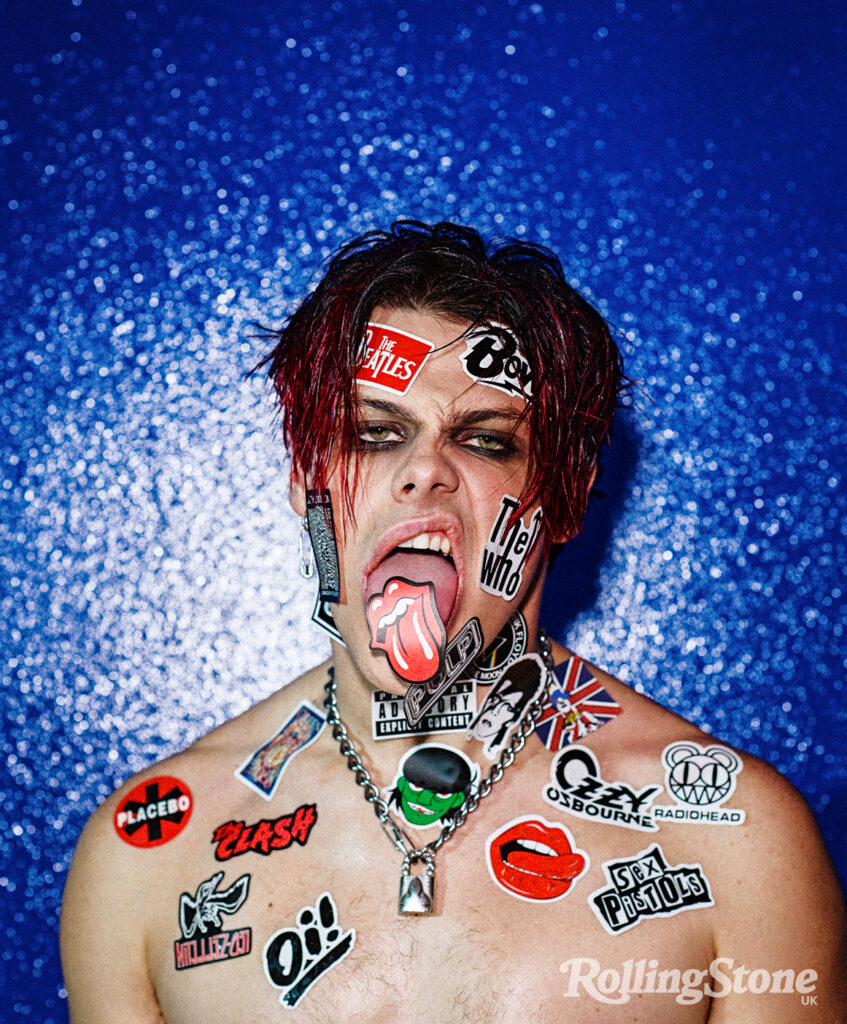

To elicit this sort of reaction, you have to be as distinctive and recognisable as the McDonald’s logo. Yungblud looks like Beelzebub cast by Tim Burton, the Joker dressed in Hot Topic or Sid Vicious signed to a modelling agency. He is loud in every way and his messaging is neither subtle nor layered. He always wears pink socks to encourage his fans to do the same and posts black hearts online as a visual sign-off. Where other artists might focus on world-building or Easter eggs for fans, he is direct. If Busted or McFly played Britpop covers, you’d be close to a Yungblud album. As he readily admits, music has not been the most important part of what he does.

“Glasto felt like retribution for me. Two years ago, it felt like exactly the sort of place Yungblud shouldn’t belong, but I so badly wanted to be a part of it”

— Yungblud

Yungblud followed an influencer business model to success. He exemplifies the way in which musicians must increasingly be social media creators before anything else. He had a meeting with Musical.ly before it was TikTok because he thought it was the future of music. “Look how big TikTok became. TikTok is like grunge to me. It’s the same shit as when someone shaved their head for the first time with punk. It’s just expression every time,” he says, adding, “My whole career came from me looking into an iPhone.” He follows TikTok trends online to see if there’s something he can recreate and he does it. For example, he recently saw that the LA Western-themed bar Saddle Ranch was discovered by users of the app, so he went there and did a video on the mechanical bull, screaming at fans to buy tickets to his US tour. He has conversations with people younger than him, like Jxdn Hossler and Travis Barker’s son Landon to understand how to keep growing his audience.

Not long ago, Harrison would wake up through the night to post on social media. He didn’t trust anyone to care as much about his online engagement as him. “I’m not an industry plant, I’m in Japan, awake at 4am to post this video,” he tells me. “But then I’m vibing — I’m still like: ‘Sick, I’m in Japan. Wow.’” That changed a few months ago because of the global growth in his profile. His team expanded to a 35-strong crew and he has three different managers. His social media is now run in part by Jules, a 19-year-old who created the most followed Yungblud fan account. Finally, he says half-jokingly, someone who would understand the importance of waking up at 4am to post.

The idea of him cancelling a run of shows because he’s exhausted is unthinkable (he sees his diagnosed ADHD as both a disadvantage and a superpower). His day-to-day tour manager explains how, after playing shows in Australia then flying to New York on a 23-hour round trip for pre-album promo, he woke up in the night and threw up from the jetlag. From there, they all went on to LA, then Amsterdam for two days and back to London for 24 hours, before going back to LA for 24 hours and then Japan. Join Harrison’s team and you are told: don’t try to keep up with him — you can’t.

Through sheer force of turning up every day as Yungblud and working in this crazed manner, he proved he can no longer be ignored as a legitimate pop-rock contender. After being initially signed in the US, and feeling snubbed by the UK, Harrison’s luck in his own country recently began to change. The first two albums were criticised for being sonically unremarkable and for clumsy lyrics that covered gender, sexual assault and mental health. But over the past 12 months, he’s achieved ubiquitousness in the British mainstream media and is close to becoming a younger household name like Lewis Capaldi or Rita Ora. In an age where beige homegrown celebrities dominate our attention domestically, Yungblud as an entity is refreshing. That media presence and personality among neutered stars who never say — or embody — much of anything at all (he will take a stab at prejudice against trans people, homelessness, most pertinent issues) is notable.

His 2022 self-titled third album altered the narrative around him on its own merit — it reached number one in the UK album chart (his second record to reach the top spot) and most reviewers were surprised. The verdict: Yungblud was… all right. He starred in his own episode of Louis Theroux’s new interview-format BBC show (other featured names include British A-listers Stormzy and Judi Dench) and played a primetime slot this year at Glastonbury on the hallowed John Peel stage, which, to him, was evidence of his UK breakthrough.

“No one wanted to admit I was as big as I was and I will admit at times… bruv, it hurt, it got to me,” Harrison says. “Without sounding wanky or self-important, Glasto felt like retribution for me. Two years ago, it felt like exactly the sort of place Yungblud shouldn’t belong, but I so badly wanted to be a part of it.”

“All I’ve got is my energy… I just say what’s true for me right now”

— Yungblud

Yungblud’s strengths are obvious even if detractors ignore them. He consistently shines on collaborations: his tracks with Halsey (‘11 Minutes’) and Machine Gun Kelly (‘I Think I’m Okay’) are two of the more memorable releases of this current pop-punk revival. He has some of the most distinctive rock vocals of the century so far — gravelly, nasal, bratty; instantly him — and is a magnetic live performer, a Tasmanian devil of pop rock. When he gets to show off, to bounce around in the context of other people, he is in his element.

It only takes an hour with Harrison to realise he is impossibly likeable; it’s how he turns haters into someone who spreads the gospel that he’s a pretty sound guy. Or, if you’re that man in Portugal, attending his show on Harrison’s guest list the following night and messaging to say he loved it. He moves through the world as if he’s Dale Carnegie road-testing How to Win Friends and Influence People. Nothing stops his optimism — exasperating, overblown optimism that persists until it beats you into submission. Cynicism is just another form of hatred in the world he says he is here to combat. He is not a fighter but a “fucking hippy”. He starts calling me by a nickname and remembers inconsequential details from a conversation I had with him a year ago. He compliments the waitress on her earrings, thanks those who have done next to nothing for their kindness. The other day in Paris he met a sculptor and sat down with him for an hour to chat about his work and life (“I was like, ‘Whoa, you’re a sculptor, that’s cool as fuck.’ Fire! You know what I mean?”). If there is anyone in a room who could leave a Yungblud follower, he will convert that stranger into a fan. You will never know if it’s conscious, shrewd behaviour and he would never believe you anyway if you told him that it was.

It’s the night before Yungblud is due to play Sacramento’s Aftershock Festival. We’re in a blacked-out car in San Francisco as Harrison worries that Roger Daltrey from The Who thinks he’s a bit fake. Across the car seat between us and without being recorded, Harrison says that while they had a great conversation when they met a month ago, Daltrey seemed confused by how he was acting up to the photographer who was there to capture candid shots of the pair. He was performing, but his hero was chill, cool, unbothered.

When I turn my dictaphone on and ask him to explain further, he says, “It’s hard for older generations to look in on new rock and understand what’s going on and like it. Every iconic picture of Bowie, he’s not looking at the camera, but you can’t do that anymore. It’s not another person’s interpretation of a moment you were doing. You have to create a moment for yourself now.”

What people don’t know about him, he says, is that he’s deeply insecure and for a famous communicator he’s bad at communicating. “Being Yungblud has been a suit of armour for me, but that’s not enough anymore. I need more, I owe my fans more. ‘Yungblud’ has just been the bridge for me to meet them,” he says. His fans, he believes, need to know the ‘real’ him and they need to experience some of his real music. “I can seem confused because all I’ve got is my energy. I believe I’m so real but I don’t step back to formulate an answer. I just say what’s true for me right now.” When you don’t have communication skills to connect with people, your energy articulates for you, for better or for worse.

He takes us to Tosca Cafe, an Italian restaurant in the North Beach area. It’s somewhere he’s wanted to go for a while but hasn’t had the opportunity. Inside, it’s like the interior of his home, he remarks: dimly lit, romantic, warm. He orders a bottle of cabernet, rigatoni and a steak cooked medium for afterwards.

“I have a massive dream: I wanna have six kids, I wanna have loads of kids”

— Yungblud

Back to the Daltrey conversation: Harrison feels extremely Gen Z himself and that’s part of the problem of how he’s perceived by older generations. “When I look at The 1975 and Arctic Monkeys, they’re such a different generation to me,” he says. “When they speak, they’re profound now. I don’t want to be profound yet, I want to be on the fucking tarmac, on the ground. I love Matty [Healy] and I love Alex [Turner] but I don’t relate to them as much as I used to. They’re older and it’s all very serious.” He lurches across the table and back again to demonstrate his comprehension of them. “I’m there and then I’m not. We’re absolutely a generation apart, there’s a big difference between us. Different brains, different way of communicating. Personally, I relate to Mac Miller, Billie Eilish, Lil Peep and Lil Nas X. That’s where my head is at.”

Over food, he explains why he’s never proclaimed to be a musical genius. “I wanna be that feeling of throwing paint at the wall and sometimes it’s gonna be a masterpiece and sometimes it’s gonna fucking suck,” he says. “I look at truly great British artists like Amy Winehouse or Arctic Monkeys or Sam Fender, they have their critically acclaimed albums on [album] one or two or three. I am not like them, I will never be like them. My masterpiece is not Back to Black or Whatever People Say I Am, That’s What I’m Not.It’s a 35-year career of making other people feel like they can express themselves. They are about the music; I am about the fucking people.” Harrison’s voice has changed: he is starting to speak in declarations and Yungblud has been switched on.

Can he be brutally honest with me? “I don’t give a fuck what people rate my albums as. It’s not about being critically acclaimed to me, it’s about connecting to people.” To me, a critic, who will not deter him from making more work: “Ultimately, I love you, but I don’t give a fuck. But I like to read [reviews] because it’s fun. I like seeing how people’s minds work.” He goes on to speak about the recent reviews for Yungblud. The long and considered Guardian piece (three stars) he enjoyed but not the snarkier Pitchfork one (four-and-a-half out of a maximum 10). At least the Guardian review interrogated his actual music, he says, and didn’t just feel like a hit piece.

Again and again, he says it’s about the people. He only cares if people are moved by what he does. “When you press play on this fucking article, are people moved by your writing?” he challenges me. “That’s all that fucking matters.” There are three Yungblud albums waiting for release. He might mix them together to make one better album but whatever he does, he’s taking his time to make something great. Then again, it might not be his best — his Back to Black or Whatever People Say I Am. “My definition of art is the expression and the imperfection of energy. I’m not right yet, but that’s my painting,” he says. “That’s what I want to say to the fucking media and to young people and to the fucking world: your journey is your painting.”

When Yungblud gets in full flow, words can lose definition and sentences are capitalised and underlined. The music press, delighted to be in the presence of vibrancy, run his speeches in full and without interpretation. They read like dramatic monologues, occasionally like copy for a “disruptive” marketing company. Here’s one of them, galvanised and well-meaning: “I want to be here to eradicate hate from preconception. That’s what I’m here to do for everyone: for you, for me, for every fucker in here, and I want to make a difference in your life even if you know it or not. Even if you never fucking hear of me, I’m gonna work my whole life to do that. Even if I never succeed, that’s my mission. That’s what turns me on, that’s my vibe. I love people and I think the world can be better.” You hear him talk and feel endeared to him and faintly roused to some unknown action. His conversation is peppered with “you know what I mean” but through his mixed metaphors you’re not always sure what is going on.

Despite his tendency to leave you bewildered, he knows that his purpose is to speak. “Some people have got hit bangers, I’m here to say things,” he says. “I love Harry Styles, I love Lizzo, I love Ariana Grande, but they say everything and nothing at all.” When his oration is used for good rather than to define what “Yungblud” is, its execution and impact fall into place. For example, ahead of September’s Firefly Festival in Delaware, Harrison had been reading up on the death of Mahsa Amini, an Iranian girl killed in her home country by morality police for not wearing her hijab. He intended to speak about it on stage and was waiting for the perfect moment, which came when their gear broke mid-concert. A recording of him discussing it was uploaded to his TikTok account. It is currently one of his most popular videos on the app with nearly nine million views.

When he returned to London, some British-Iranian girls approached him to say they’d seen the video online and thanked him for speaking about the human rights violation. After they left, he found himself getting emotional (“that means more to me than being number one in the singles chart”).

While he works on creating a great fourth album, he will keep his inner circle tight. This includes Jesse Jo Stark, his fashion designer and musician girlfriend. He first met her in 2020 when he cast her in his video for ‘Strawberry Lipstick’. “She’s been so centring in my life, she’s just my best friend and I wanna hang out with her all day,” Harrison says of Stark. “I wanna hear her talk. I love what she’s got to say. I love her views on the world, even if they’re not the same as mine. I just think she’s who I was supposed to end up with. She’s cynical and we can’t combat each other because I’m so optimistic. So, I bring her out of her shell, and she grounds me like no one else.” On their further differences, he adds, “She’s the most rock’n’roll person I’ve ever met. I say I don’t give a fuck but I do a little bit. She does not give a fuck. It’s like, ‘Wow.’” Eventually he wants to have a huge family. “I have a massive dream: I wanna have six kids, I wanna have loads of kids, even if I adopt them as well.”

“If I’m in the studio on my own, I’ll give it 60 per cent. If you’re in there, I’ll give you an iconic take in one”

— Yungblud

Until then, he’ll finish post-album promo and enjoy the response to his short film based on his song ‘Mars’, which stars talent from the trans, nonbinary and wider queer community. He will design some clothes and write a musical for theatre, a prospect that seems objectively ideal for him. He will work with Avril Lavigne, an artist he’s loved since he was 11 years old, on her next album: “She’s in a place where she’s centring herself and thinking, ‘What does Avril Lavigne do best?’ She’s on fire. I want her to get a Grammy on this album. That’s what I keep saying to her. They’re songs, man.” Almost every day in his schedule until September 2023 is accounted for. In the spirit of moving into this more considered phase of his career, he will take a month off around Christmas to recharge. He and Stark will stay at Lenny Kravitz’s house in the Bahamas, to drink from coconuts and attempt to do nothing.

Harrison’s team believe that his classic rock album will exist when they finally manage to put his larger-than-life live performances onto record. “Every producer I’ve ever worked with, their opinion is of how to harness me: ‘We’ve got to put what’s on stage in a record,’” he says, the only time over a series of days he shows any irritability. “I’m like, ‘Yeah, I know. I’ve been fucking trying.’ Every time, it’s chipping away.”

As we finish our meal, we talk about how he might do that. “There’s so many writers on my records who didn’t write a fucking word, but they were in the fucking room, so I have to give them publishing,” he says. “I sit and I write the songs, but I need people to be there to perform to. If we were in the studio, part of me wants to impress you so I’d nail it. Do you know what I’m saying? If I’m in there on my own, I’ll give it 60 per cent. If you’re in there and, I don’t know, Jared Leto’s in there, I’ll give you an iconic take in one. It’s my energy — my energy doesn’t lie.”

The next day I got to witness the Yungblud personality at 11. We travel in a minivan with his crew from San Francisco to Sacramento. Hard-rock classics are selected by Harrison and his day-to-day tour manager: Airbourne — ‘Runnin’ Wild’, Sublime — ‘What I Got’, Kid Rock — ‘All Summer Long’. Harrison laughs reading the festival line-up for the day on his phone. In an obnoxious American voice he says, “Airbourne, Papa Roach and Yungblud: This. Is. Aftershock.” A significant percentage of this US crowd aren’t going to know him but that ability to successfully preach to future enthusiasts is exactly what he says he wants me to witness.

On the drive, Harrison shoots out the opinions of someone who is always deeply enthused or appalled by the topic in question. Mary-Kate and Ashley Olsen (“What a bunch of legends”); bro-country duo Florida Georgia Line (“Fire, bruv”); the fact one of his crew used to eat the British chocolate bar Twirl wrapped in a Fruit Winder (“Fucked, bruv”) and as he enters US fast-food restaurant Chick-fil-A (homophobic politics: bad; chicken: unreal, delicious), he says, “I’m a big bi boy walking into Chick-fil-A to fuck shit up.”

By the time I step off the van with everyone else and walk to the artist trailers, Harrison has beaten us there. He’s already out in the swampy oppressive heat wearing black layers and lobbing bean bags across to Papa Roach’s trailer. His team is barely cognisant of anything, searching for bottled water or tentatively taking their damp shirts off. Around the main stage, security hose down the crowd for their own safety. Ten minutes later, Harrison is still tossing bean bags around to amuse himself and shouting to his friends.

As we approach his set time, Harrison emerges from his trailer like the Kim Kardashian peeking bush meme, holding a scoop of white electrolyte powder. “Anyone want any Charlie?” he shouts, creasing at his own joke. He is in hyper-active kid mode now. He strides around asking if his shorts are too revealing or if he should put another pair of boxers on (he knows the answer and acts accordingly). He continues the Tommy Lee impressions he began the night before at a bar: crisp, almost parrot-like (“Holy fuck, I fucking love rock music”). Next come the full-bodied Jim Carrey skits from The Grinch and The Mask — scarily accurate. His team, used to such shenanigans, take longer to become infected with his humour than me but when they get there, it only encourages him more.

It’s golden hour when Harrison and his band take to the stage. The turning point in the set, the moment he wins enough of the crowd over, comes about halfway through when he asks: “Does anyone think we’re shit?” Some answer yes. “Does anybody think we’re fucking great?” People make a lot more noise. “Well, that’s told you, innit!” They laugh at this frankness and settle into what he has to offer.

Afterwards, a promoter for the festival comes up to him and says that if his next album does well in the States, they’ll get him to headline. Older male rockers congratulate him on his set. “Those are the seats in the arenas, those are who you need to get to grow an audience over here,” he tells me conspiratorially. Anything feels possible. As if he overheard our conversation from the day before, a middle-aged man approaches to shake Harrison’s hand and says, “Your energy is unbelievable.”

On the drive back to San Francisco in the dark, his team is knackered and overheated, either asleep or heads down, earphones in. After a while, Harrison climbs into the empty front seat next to the driver (“What’s your name again, brother?”) and starts DJing to himself. First, he plays Blondie’s ‘One Way or Another’, the song typically used in movie scenes or adverts to soundtrack an underdog character’s attempt to win someone over. During Patti Smith’s ‘Because the Night’, Harrison mouths the lyrics and performs jazz hands to an imaginary audience through the windscreen. When The Beatles’ ‘A Hard Day’s Night’ plays 20 minutes later, someone notices that Harrison is unconscious, mouth open. I lean in to make sure he’s not messing around as they say, “I’ve never seen him asleep in my whole life.”

Taken from the December/January 2023 issue of Rolling Stone UK. Buy it online here. On UK newsstands from Thursday 10 November 2022.

Photography: Kosmas Pavlos

Fashion: Joseph Kocharian

Grooming: Georgina Hamed using Balmain Hair Couture

Photography Assistants: Luke Johnson and Ben Turner

Fashion Assistant: Sacha Dance