We can work it out: Inside the world’s first Beatles master’s degree

A rare look behind the scenes at what it’s like to get a Master’s degree in The Beatles at the University of Liverpool — and why people across the world pay thousands of pounds to do it

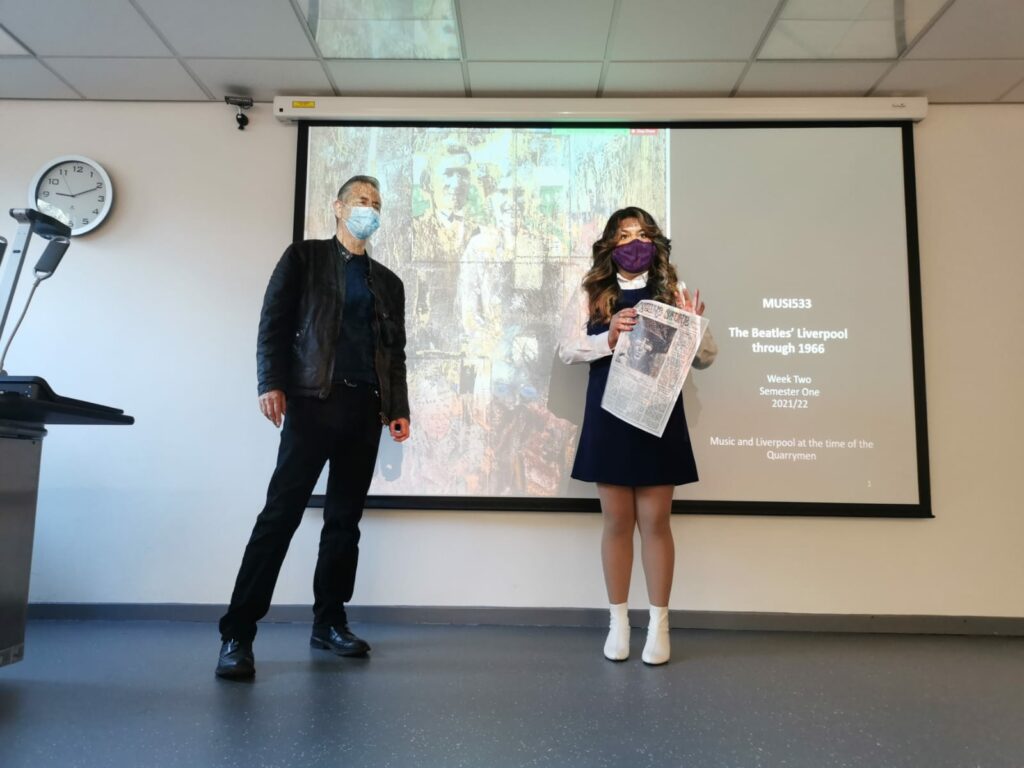

It’s 9am in a chilly lecture theatre and a maintenance man just strolled past the door whistling the melody of the Fab Four’s ‘She Loves You’. There’s a girl dressed like it’s 1966 to my left, and a man with a ‘Yellow Submarine’ tattoo to my right. Class is in session for the Master’s programme, The Beatles: Music Industry and Heritage at the University of Liverpool.

Today we’re learning about the history of Liverpool’s music scene, from the Lennon and McCartney families’ ties to the 19th-century music hall, through to the folk subgenre, Skiffle, the sound mined by the Quarrymen on their way to becoming the Beatles. Dr Mike Jones is deconstructing the misconception that the Beatles were straight-up rock ’n’ rollers. Yes, they were influenced by Little Richard and Elvis Presley, but before them, they were immersed in the local sounds of Liverpool: music hall choruses, Irish sentimental songs and parodic nursery rhymes.

On one of the slides, there is a quote: “Thanks to the Beatles, Liverpool and music are synonymous.” I remember a previous class in which Dr Holly Tessler, the founder of the programme, explained how the “Northern-ness” or “Liverpudlian-ness” became a key part of the Beatles’ brand in the early 60s. Before them, the Merseyside area was known for its comedians, not its music. Through the grand Beatle narrative, the Fab Four transformed into the ambassadors not only to Liverpool’s music scene, but also to the entire city.

Now is the most crucial time to be an academic on the Beatles – or anything from that era, in fact. We’re on the bridge between lived history and past history. Soon enough, we’ll be without the primary sources; in the murky waters of remembrance, and mis remembrance, relying on the boozy anecdotes of old-time regulars at The Cavern Club. Dr Tessler understands that. “Why are the Beatles releasing [documentary series] Get Back? Why is Paul McCartney releasing The Lyrics: 1956 to the Present?” she asks the class. “Surely, it’s because they’re seeing this as their last opportunity to get their side of the story out there, in their own words, while they still can.”

On one of the slides, there is a quote: “Thanks to the Beatles, Liverpool and music are synonymous.”

The Beatles embodied a zeitgeist that captured the world for nearly a decade. Their impact continues to trickle into every inlet of popular culture, from influencing major music franchises like The Monkees and Oasis, to the Abbey Road album cover repeatedly being referenced in TV shows and movies. “After World War II, suddenly the Beatles culturally unite the UK, Germany and the USA,” says Dr Jones. “So, the Beatles almost heal the wounds of the war – that’s how important the Beatles are.”

As a PhD student sitting in on this Master’s programme, my memory takes me back to when the Beatles inspired me to move from Texas to London to pursue my undergraduate and Master’s degrees. I’ve always been a devout Beatles fan, but my academic fascination with the group began as I recognised many intersections between their music and English Literature. While writing my dissertations on the Beatles, I encountered a certain amount of departmental push-back. I was told I couldn’t compare the Beatles to Shelley, but I did anyway. Today, in Dr Jones’ lecture, I mention my thesis on the legacy of Romanticism in the Popular Music of the 60s and 70s, and no one tells me I’m in the wrong room. “Higher education and high culture are the same people,” explains Dr Jones, “they are the keepers of what is acceptable academically, and what is unacceptable culturally.” Over the past 20 years, the study of pop culture has almost become normalised, but that’s mainly happened because of how much people love music. For a long time, Liverpool has pioneered this kind of study. In 1988, The Institute of Popular Music Studies was founded here in Liverpool, the very first institute of its kind.

“This isn’t the world’s biggest pub quiz, it’s a critical degree and students are going to have to do a great deal of analysis.

Some may hear about a degree in the Beatles and think that students are paying to over-intellectualize the Beatles’ music, but it’s really about combining the creative with the corporate. As Dr Tessler puts it, “This isn’t the world’s biggest pub quiz, it’s a critical degree and students are going to have to do a great deal of analysis.” It’s true. The graded components comprise standard analysis of text and written reflections, a pitch for a Beatles-themed cultural event in Liverpool, a business plan, and a city-wide walking tour designed around a hidden history of the band. Master’s student Dominic Abba sums it up well when he tells me, “To study the Beatles is to study the impact they had not just in music, but also in Business and Industry Studies.” That said, arguments like “What’s the best Beatles song?” or “Who’s the most handsome Beatle?” frequently erupt over an after-class pint.

It does beg the question, though: who would commit to study something like this? Dr Richard Mills, author of The Beatles and Fandom, describes these students as “Aca-fans, they are Beatle fans first, who are now treading on the leaves of academia.”

“My family wasn’t at all surprised because I’ve been a die-hard Beatles fan forever,” says MA student Dr Susan Peterson from Illinois, in a statement echoed by each student and lecturer. Beatlemaniacs know most facts about the band already, but it’s the point of view that’s placed on top of the facts that illuminates something new. The Beatles are the starting point for discussion, rather than an end point.

While walking us through the history of Liverpool’s music industry, Dr Jones asks for reflections from the recent class trip to St Peter’s Church, the place where John Lennon first met Paul McCartney in 1957. Adjusting her psychedelic necktie, one student admits, “I found it hard to compartmentalise my inner fan-girl while trying to think critically.” Pursuing this degree, students get a clear view of museum and exhibition infrastructure with a specific focus on popular music. In a dream world, some of us could end up working at the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame or the Museum of Pop Culture. As Dr Tessler tells us, “We’re using the relationship between Liverpool and the Beatles as a template for how you tell different popular music stories in a geographical place.” John Lennon wrote the wonderfully bizarre lyrics to ‘I Am the Walrus’ to get his own back at schoolteachers who attempted to analyse Beatle lyrics as poetry.

While it might seem like a lot of money to sit and ponder the meaning of “I am the egg man / They are the egg men / I am the walrus,” there is an invaluable impact that the Beatles made on the music industry and the heritage sector. That is exactly what we all come to Liverpool to explore – that, and the true meaning of “goo goo g’joob”.