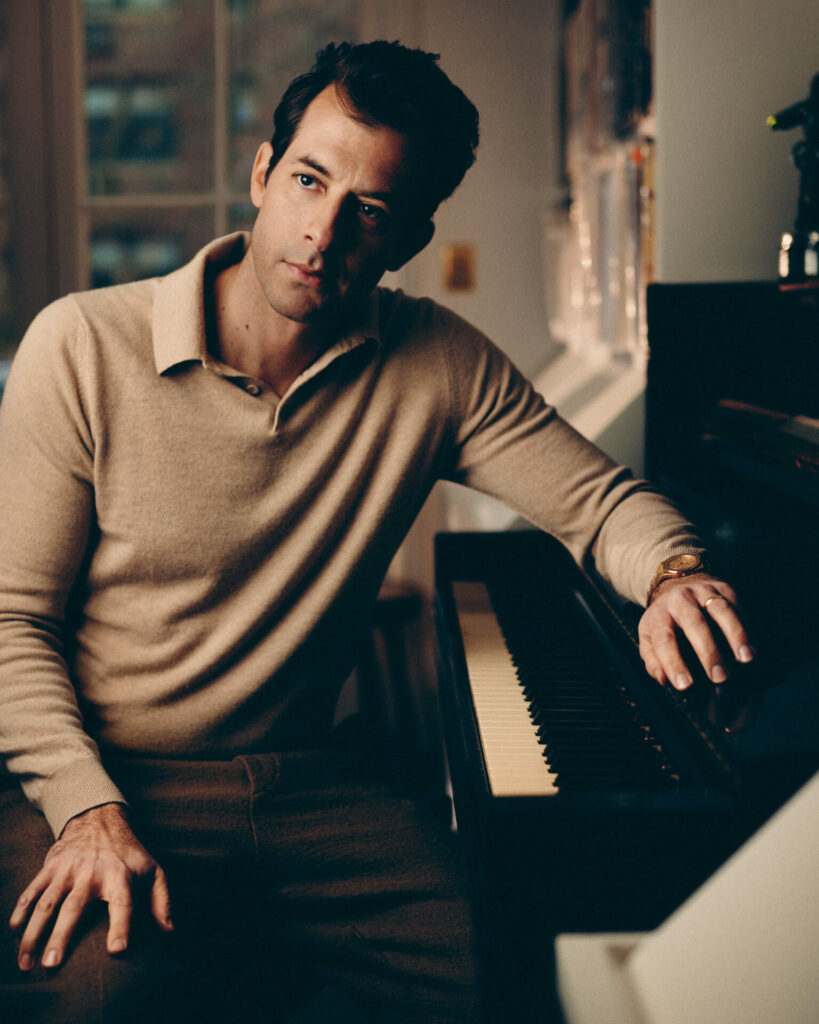

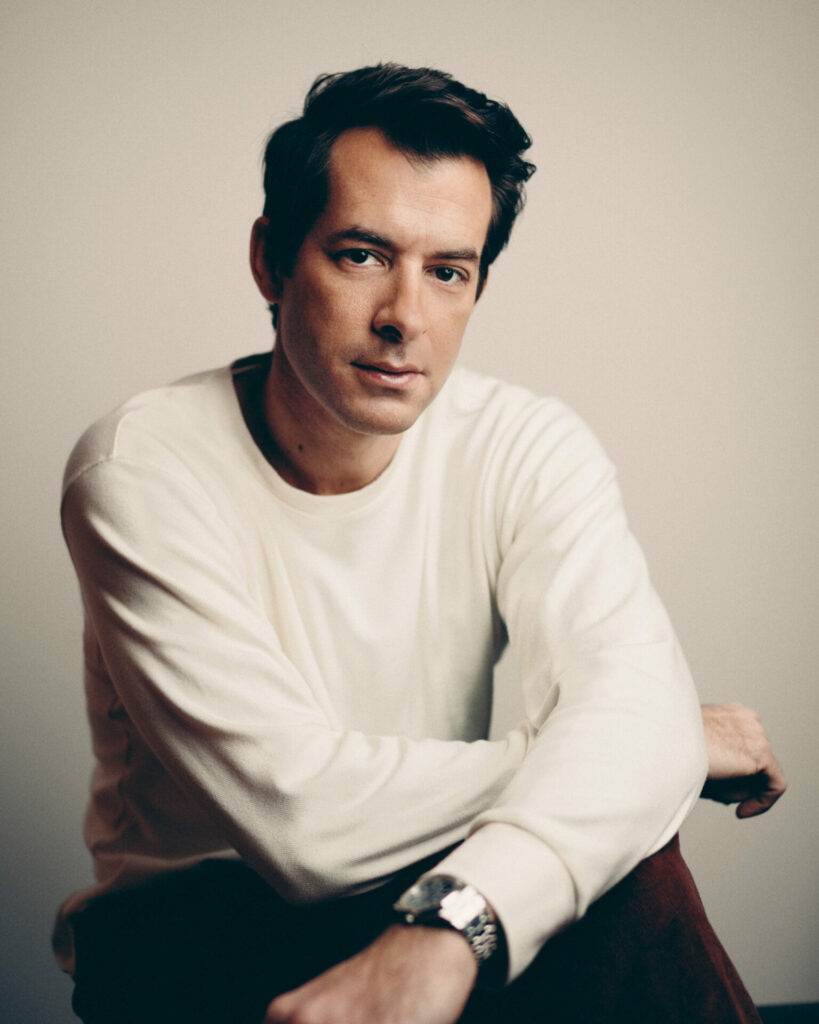

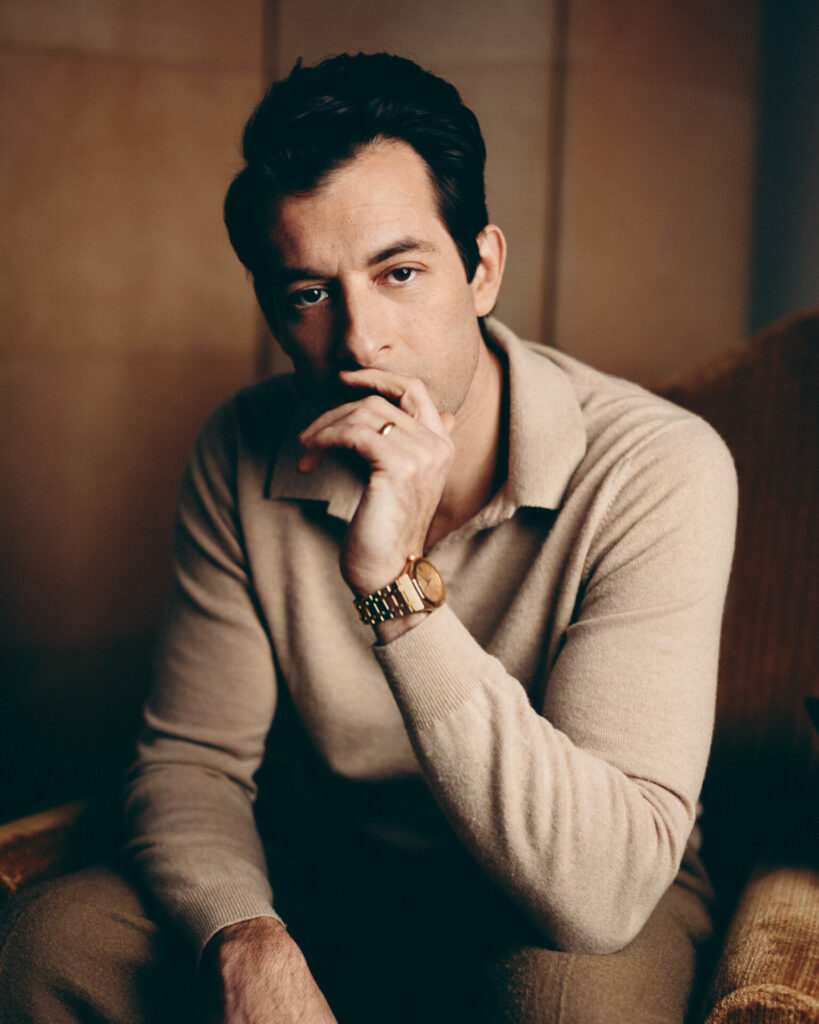

The rebirth of Ronson: Mark Ronson on fatherhood and his first film score

Songwriter, DJ and record producer Mark Ronson has been through a period of renewal. Following divorce, he’s now happily remarried and has become a dad for the first time in mid-life. Not only that but he is turning his attentions to a new skill: composing a film score, as he tells Rolling Stone UK

Promptness isn’t a virtue you’d usually expect from a record producer — especially first thing in the morning — but Mark Ronson has an excuse for running late that’s undeniably valid, and it has nothing to do with having spent an extra-long night in the studio, or watching a buzzworthy new artist perform in a crowded club until well past midnight. On the warm and sunny morning that he’s scheduled for an interview in his downtown Manhattan studio, he’s been spending time at home with his baby daughter Ruth, who was born a few months ago.

“I was leaving this morning, but I hadn’t got a smile out of her,” he explains, settled onto a stool in the studio’s control room, in front of stacks of speakers and a vintage recording console. “I was like, ‘I’m late, but I can’t leave until I see her smile this morning.’ I mean, it’s so clichéd, but everything she does is completely enchanting.”

Certainly, Ronson’s life is in quite a different place than when he wrote his last album, 2019’s Late Night Feelings. That record — which featured vocals by artists like Miley Cyrus, Camila Cabello and Lykke Li — was inspired by the end of his marriage to his first wife, Joséphine de La Baume, who he divorced in 2018. These days, he’s happily remarried to actress Grace Gummer, enjoying the experience of being a new father, and working on a musical project — more of which in a minute — that deliberately affords him a more manageable schedule than he’s had in the past.

“I feel like it’s sort of exactly where I’m supposed to be,” he says. “I’m working on something where even if it’s long hours and a lot of work, I can be home by 7 or 8 every night. I’m not on the road; I’m not running around; I’m not at the mercy of some young artist who likes to work from 3pm to 1 in the morning. For the most part, I’m getting to be home and devoted and relishing this really amazing other thing that’s going on.”

The “something” that’s in the works isn’t a typical album by Mark Ronson — as hard as it is to use the word typical to describe his music and the ever-revolving mix of different styles, eclectic influences, collaborators and players that has become its trademark. For the past few months, he’s been composing and recording his first-ever film score. He’s not at liberty to name the film or talk about it in even the slightest detail — which he apologises profusely for — but he seems to be savouring the process of being immersed in a brand-new type of project.

“Film is just so different, because you’re just surrendering to the visual and you’re trying to create a sort of unspoken emotion within whoever’s watching it,” he says. “You have to surrender some of that ego and that need to constantly be blowing people away. When you’re doing the music for the film it’s very important, but it’s actually not about you. I mean, obviously a great score can make a film or ruin a film, there’s no doubt about that. But there’s something about it that, no matter what’s happening, you’re usually not the most important thing going on at that moment.”

As with his albums and singles, Ronson’s score so far has been inspired by a dizzying array of artists and genres. He says that his influences have included the work of everyone from legends like Angelo Badalamenti and Elmer Bernstein to the score of The Goonies. In addition to being, as he puts it, “a movie fanatic”, Ronson’s love of hip-hop fostered an appreciation for (sometimes obscure) vintage movie soundtracks.

“The scores of 60s and 70s soundtracks were, like, this treasure trove for sampling,” he says, especially during the “sort of eerie Wu Tang-ish era in the 90s. All those Enter the Dragon and [Ennio] Morricone scores. If you were looking through a record bin and you saw one of those, you’d be like, ‘Oh, I bet you that has a good loop on it.’”

The score should be done soon. In the meantime, he’s playing a noteworthy one-off gig: a show that will be the finale of this year’s Montreux Jazz Festival in Switzerland. The evening, scheduled for 15 July, is presented by the watch brand Audemars Piguet, of which Ronson has been an ambassador since early last year. The gig’s lineup is billed as “Mark Ronson and His Favourite Band Ever”, and included are some of the musicians who played on Amy Winehouse’s Back to Black album — people like Dave Guy, Ian Hendrickson-Smith, and Homer Steinweiss — as well as singers who have worked with Ronson, like Yebba and Lucky Daye, with some surprises in store, too. Ronson’s role, he says, is to be “conductor slash DJ programmer on the night”.

“I didn’t want to just go to Montreux,” he recalls, “so I decided to creep in this concept of going with some of the greatest musicians I’ve ever recorded with, and also in some ways, celebrate them as the unsung kind of heroes. People in the know, and who read liner notes, certainly know who those guys are. But just this idea of the guys who played on Back to Black and ‘Uptown Funk’, and ‘I Need a Dollar’ by Aloe Blacc and Charles Bradley — these guys behind all these amazing records that people love, that people might not know on a first-name basis, celebrating all their music on the stage.”

Ronson has, of course, been involved with his own long list of undeniably impressive records which has earned him BRIT Awards, Grammys and an Oscar. He’s worked with a myriad of successful artists — from Lady Gaga to Adele to Paul McCartney to Queens of the Stone Age, to name just a few. But Amy Winehouse’s Back to Black, released in 2006, is still, for many people, his career-defining moment so far. Why does he think that album has had such a strong and long- lasting impact? “She was so incredible — her character and personality and what she represented. All of it is wrapped up in it,” says Ronson. “It’s hard to disentangle any of it, why she will always continue to mean something to people, but I’m just obviously proud of any part that I had in it.”

Like Winehouse, Ronson has performed at many summer music festivals over the years, including Glastonbury, Pukkelpop and Bestival.

” I love those festivals, especially the great ones,” he says, smiling. “I think Europe has so many amazing festivals, and when you’re starting out, you don’t know anything about them. You’re like, ‘Wait, I’m in the middle. What is this place called? We’re in the Netherlands? OK.’ And you go out on stage and you’re like, ‘These people are incredible.’”

The Montreux Jazz Festival, at which he’s performed several times, stands out in particular. “It just has this rap,” he says. “It’s like everybody knows that you’re going in, you’re going to see some brilliant music. You’re going to have your mind expanded a little. You’re going to have some sophistication; you’re going to have some joy; you’re going to have some dancing. I guess the fact that it’s rooted in jazz, rhythm, blues and soul makes it sort of special as well.”

After the score he’s working on is completed, he’ll resume focus on his upcoming album, the follow-up to Late Night Feelings. “I was starting the record and this film came along and just ate every piece of bandwidth that I had,” he recalls. He’s also writing an accompanying book about New York City’s vibrant nightlife scene in the 90s. “I’m so immersed in that while I’m writing

it — talking to every old bouncer, every other DJ, every promoter I knew, all the people that came out dancing — I can’t help but think that won’t inform the music as well.”

Essentially, the book will be, in part, a memoir, but it will also document and recount a seminal period in New York City, and music in general. “I’m remembering how unique and special that time was, not for the obvious reason that I was coming of age, but because it was before camera phones and bottle service and banquettes and all these things, and even the smoking ban in the clubs,” he says. “There was just a very magical era.” Although he’s a first-time author, he’s not intimidated by the process. “It’s not that dissimilar to when I’m sitting here [in the studio] writing, or in front of the computer comping a vocal. It’s very meditative, because it’s just only you and the screen, the thoughts or whatever’s going on.”

To write the book, he adds, he goes down to the basement of his New York City home — “a shitty cellar where we live” — to concentrate on the work at hand. “I love regimen,” he says. “I love order. I can, just like anybody in our day and age, get distracted as hell.”

At the age of 47, his lifestyle is much quieter than during his days of clubgoing every night and touring extensively. “I did start with the family a bit later in life,” he says. “I have friends who have kids that are 14 and 15 now, and I can look at them and be like, ‘Wow, you’re kind of empty nesters. We’re the same age and you’re about to have full freedom.’”

Instead, those friends might say, as Ronson puts it, “You just did it the other way — you had all your freedom.”

“I think that that’s absolutely the case,” he admits. “I’ve had every single cocktail party, social engagement and fancy dinner I ever need togotofortherestofmylife.Soit’sagood thing, because I don’t have time for any of that now. And I’m sure that will come back. But since Ruth came along, it just means that every time I’m working, it better be the most important thing I can be doing for work, and if I’m going to travel, it better be the most exciting show and something that I know is going to be so special.”

Will fatherhood, a happy marriage, and an overall sense of contentment influence his upcoming record? “A loved-up daddy 90s album,” he suggests with a wide grin. “Who knows?”