i.

I’m watching the side profile of Matty Healy from his right as he formulates an answer in slow motion. The light is hitting him from his left through sheets of glass that showcase a Japanese zen garden. I had expected quicker responses from The 1975 frontman. Known as the spokesperson for the millennial generation — in the world of music at least — he’s always ready with a striking quote or, until recently, a tweet that will elicit praise and fury in equal weighting. But that’s not him any more. He no longer wants to be a mouthpiece and he certainly doesn’t want to become more famous than he already is.

He basically looks like Auguste Rodin’s The Thinker, if the sculpture was smoking a spliff and wearing tan Tabis. I write that with the implied smirk I believe Healy would approve of. He’s a man who lives the impossible task of balancing extensive use of cultural references and self-awareness; a man who has a first edition of Infinite Jest with a bookmark placed a quarter of the way through for display in the next room, partly because he’s a David Foster Wallace fan but mostly as a nod to that joke about everyone having a copy of it a quarter-read. A man — white, straight — whose willingness to talk about art and ideas has sometimes been viewed, in our postmodern, nihilistic and hyper-consumptive era, as pretentious. He thinks his brain works fast rather than well but he’s sharp enough to be the person who captured what people think of him best in a 2016 Rolling Stone interview: “quite obnoxious but quite sincere.”

This introduction should be read as playful, not only because Healy is funny and likeable, but because he explicitly told me not to write that he’s taking dramatic pauses. In fairness, they’re not dramatic so much as they are active. This is the first time he’s speaking about his forthcoming album to a person outside his inner circle, someone who is here to professionally question him after he said in 2020 that he was doing his last interviews. “I don’t like it that much because it’s so scary,” he explains of the process. “I think I’d gotten to a point where I didn’t know how much I wanted to qualify my statements.”

“There’s always been a lot of ‘will they, won’t they’ with my band. Will they split up? Will they not? Will I get over drugs…? I love the drama of it”

— Matty Healy, The 1975

Being a mouthpiece had become genuinely exhausting after years of inadvertently saying he feels like the messiah sometimes, hypothesising that dating Taylor Swift would be emasculating and ad-libbing about misogyny in hip-hop. He was drawn into a cycle of repenting and re-offending for such things, the majority of which occurred in the media or on social networks. But it’s equally true that doing interviews was an unwelcome reminder that being Matty Healy is a job. One that didn’t suit someone who is a “big man child” sometimes. Being 33 — his current age — does not mean going (and he says this in a Kevin the Teenager voice) “I don’t want to do that.” This stretch of his life is about showing up and doing what needs to be done.

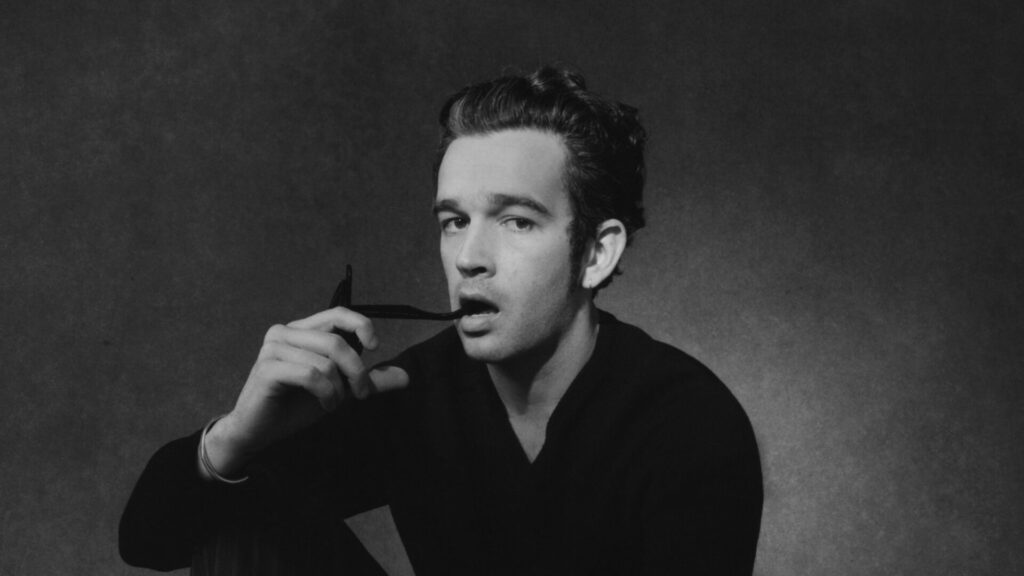

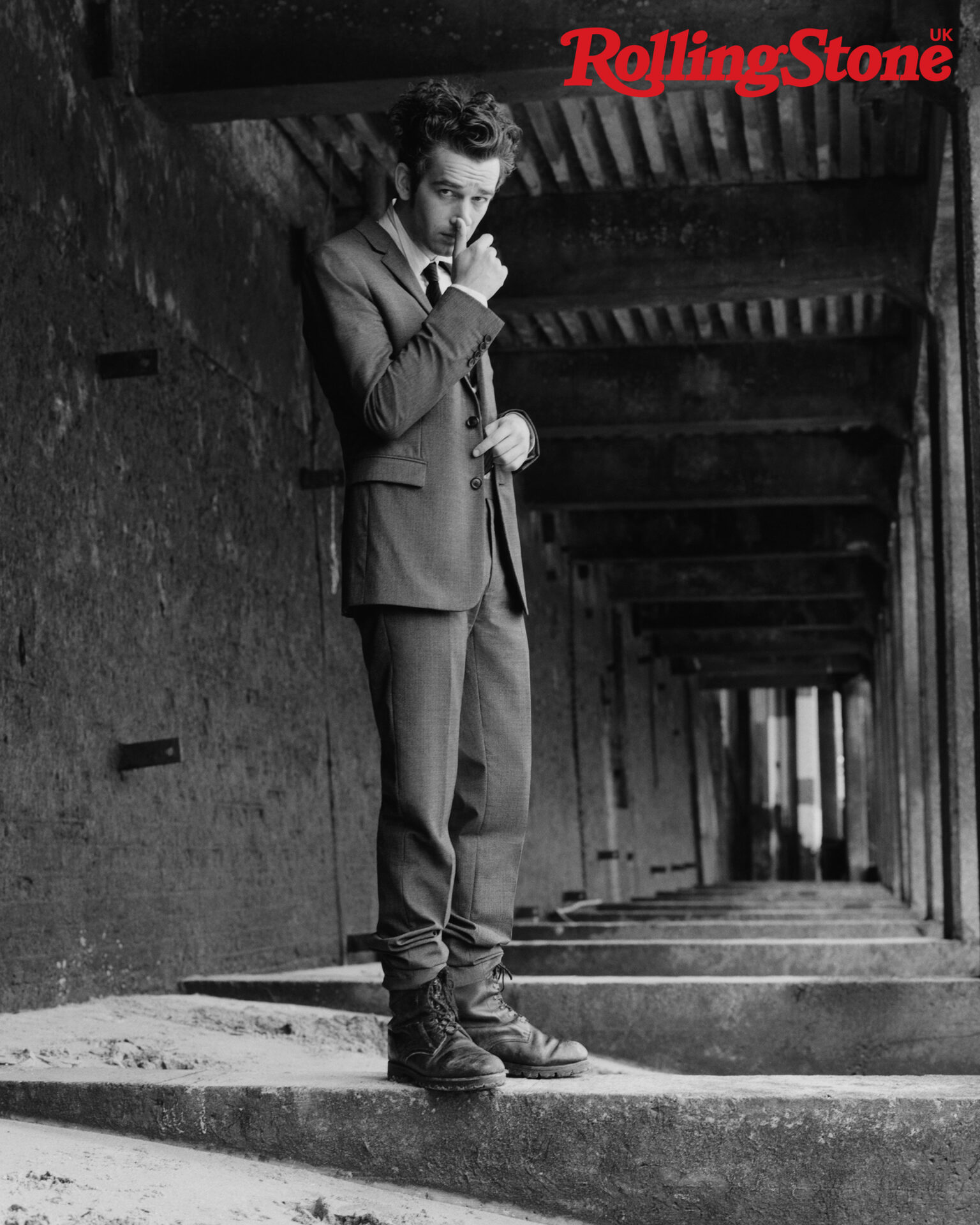

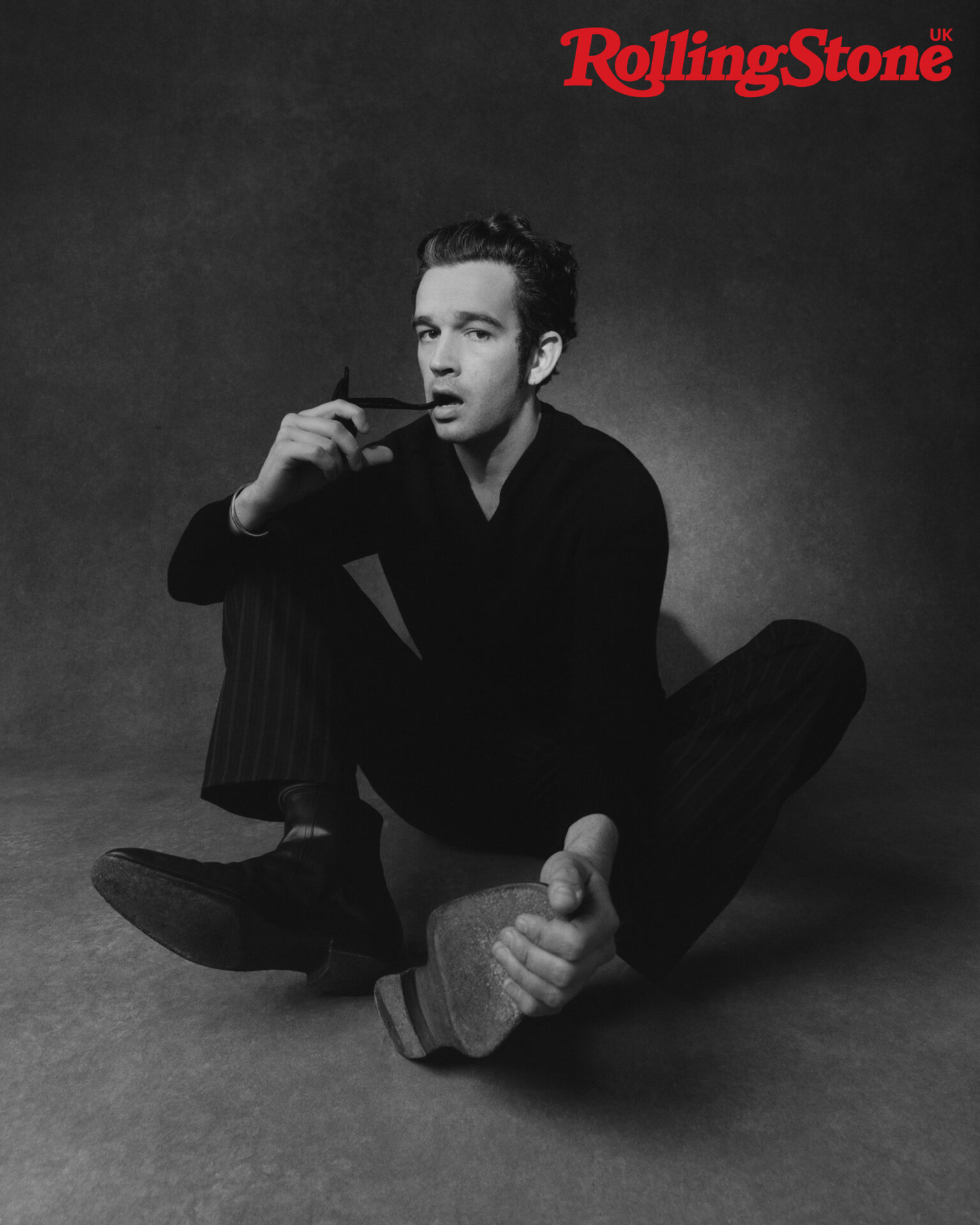

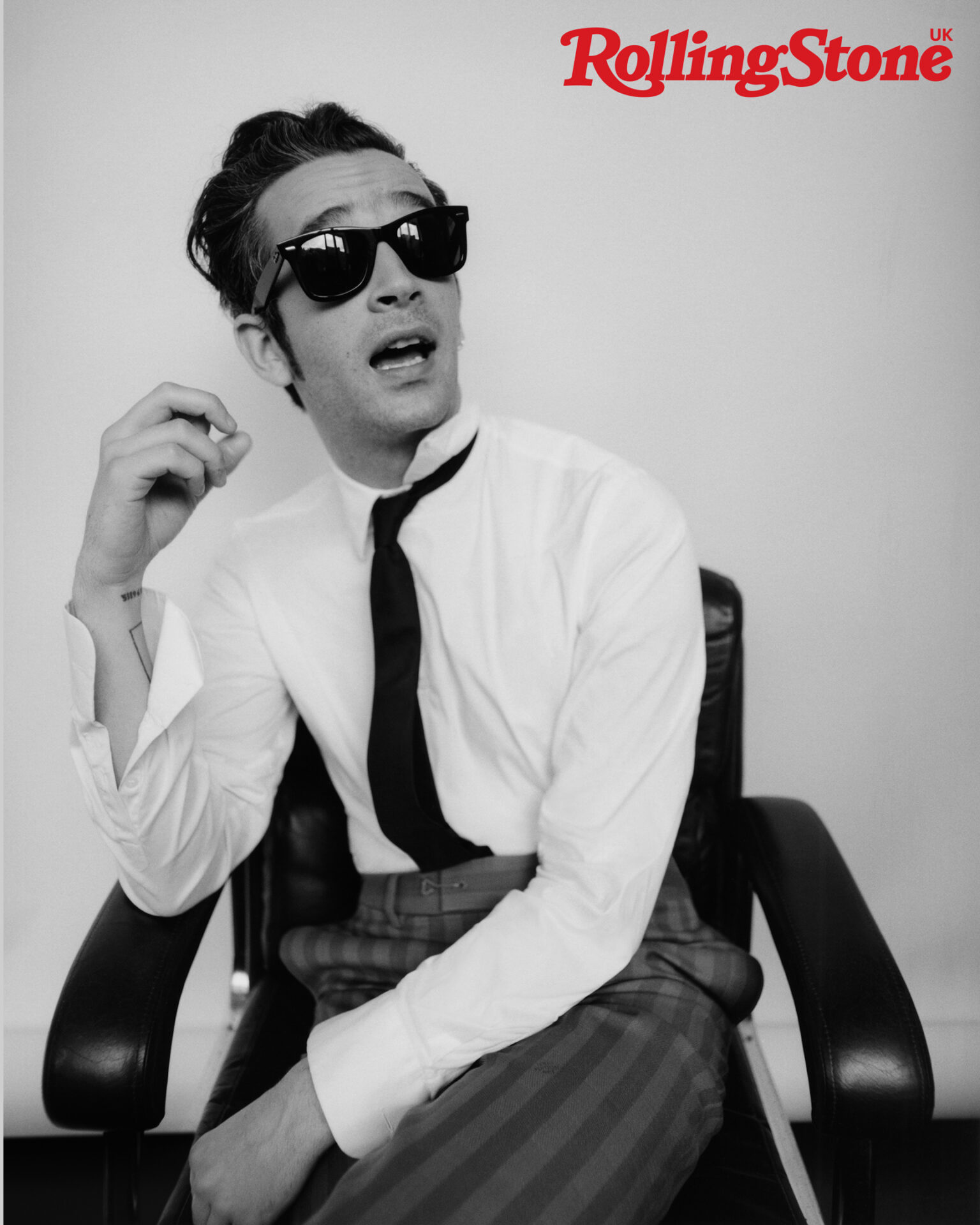

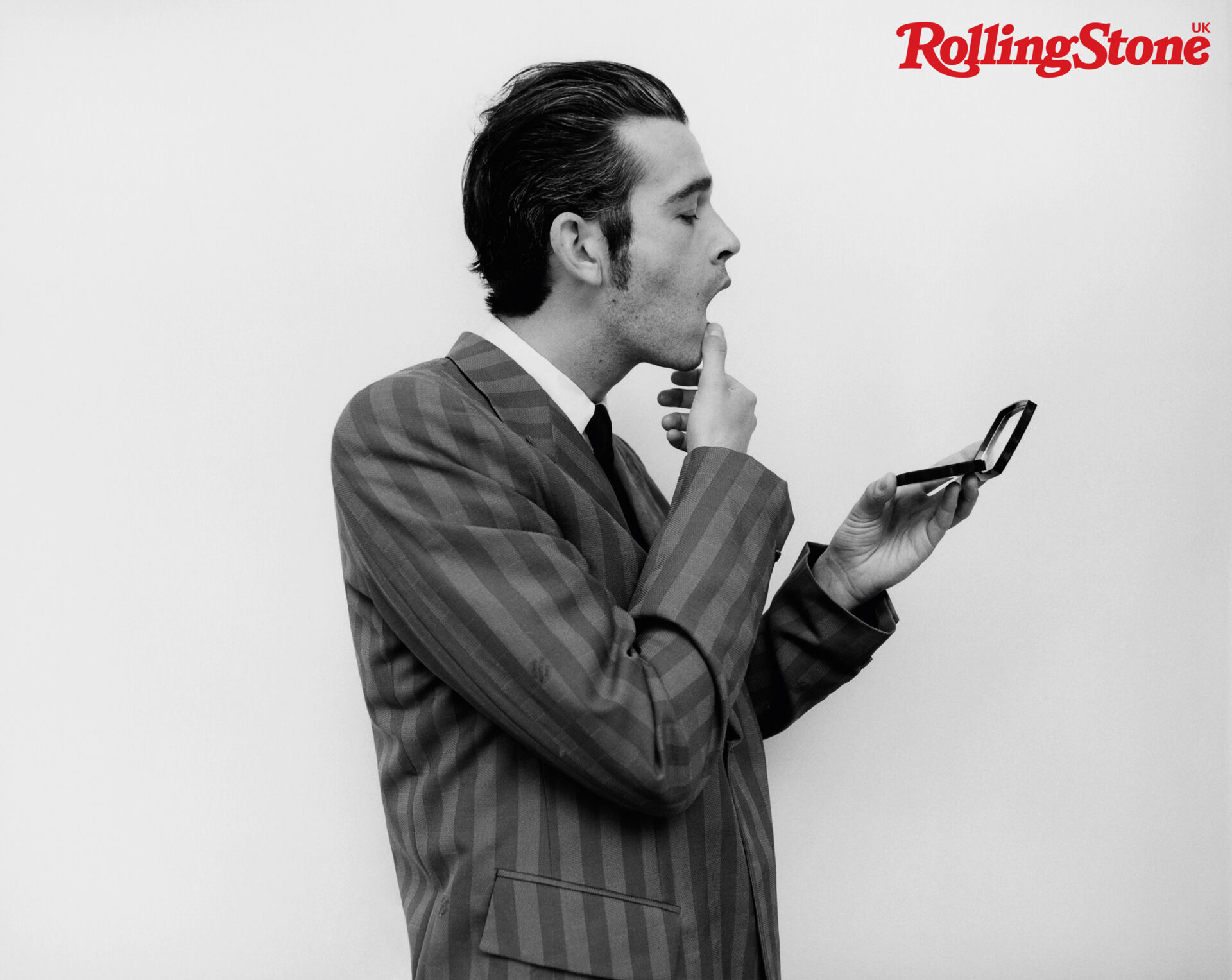

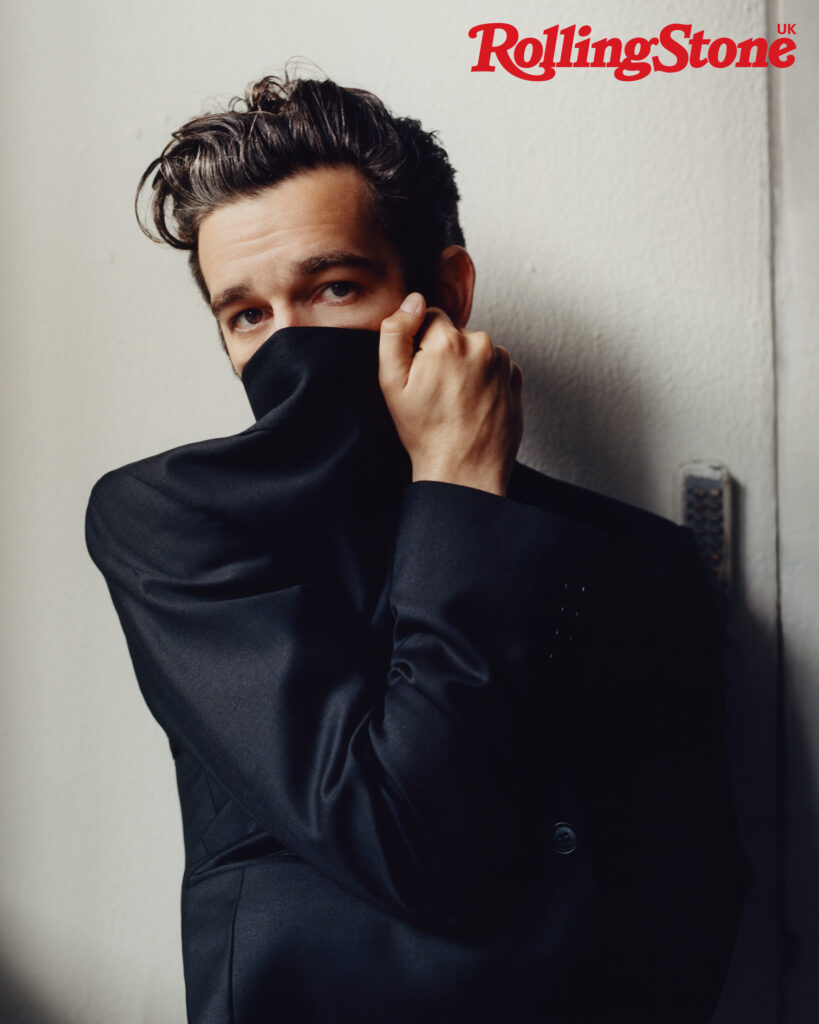

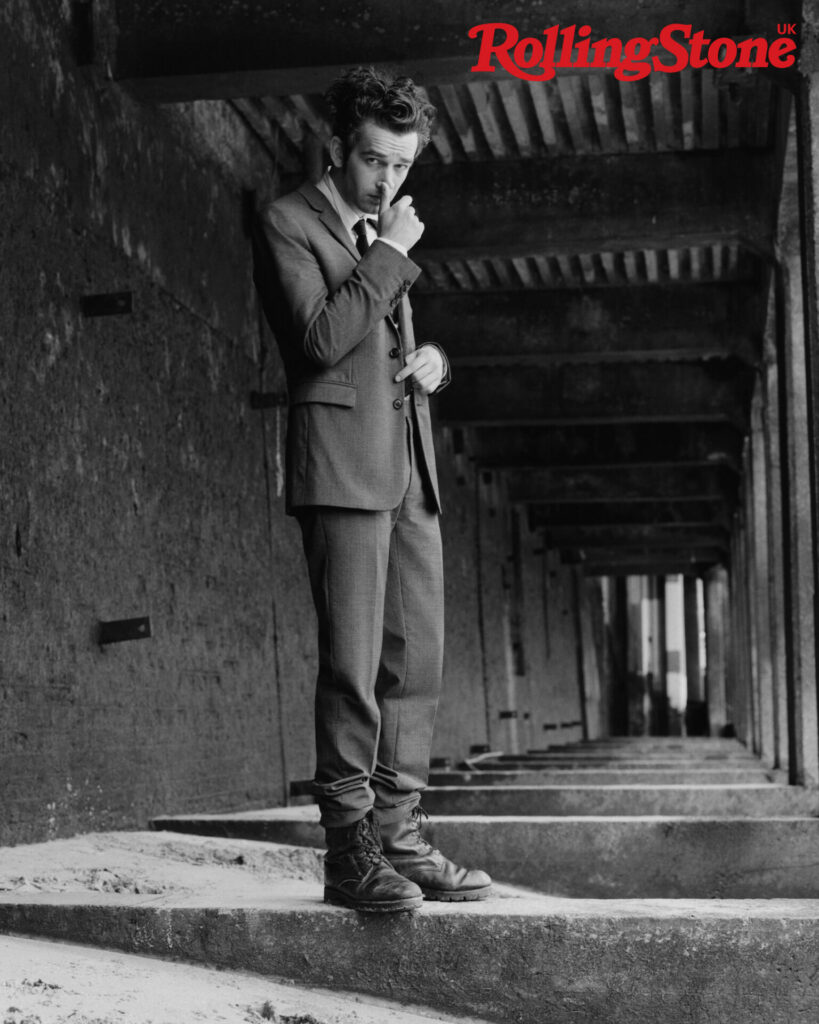

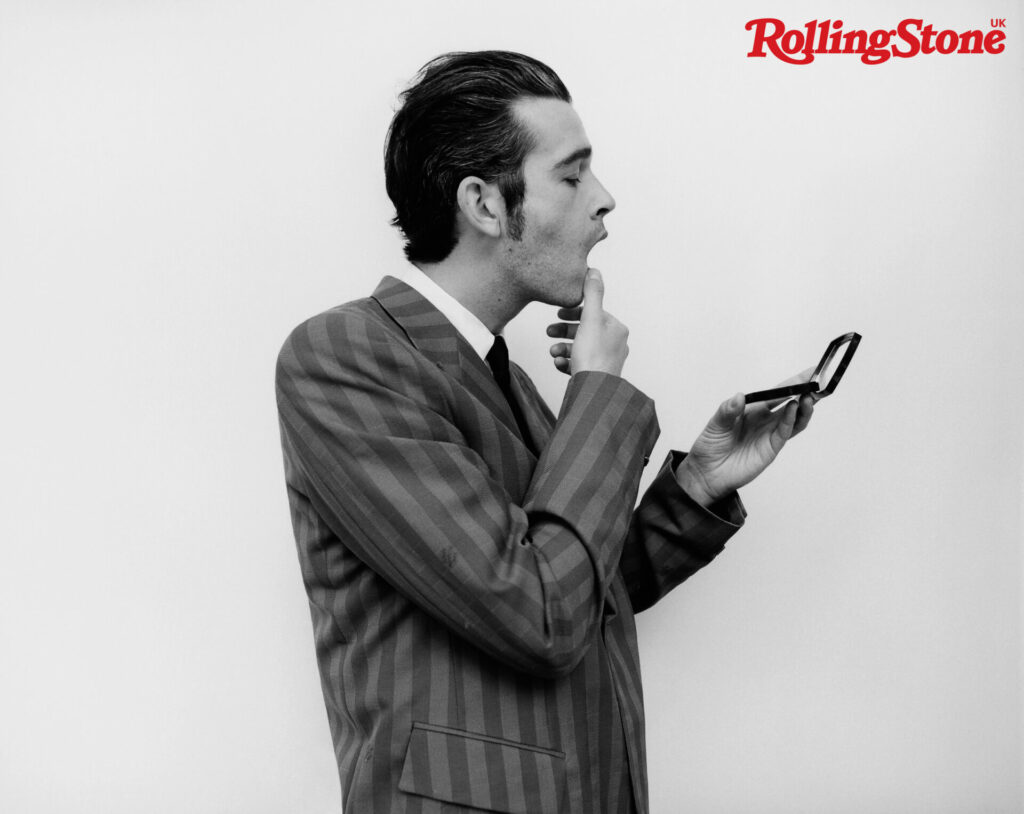

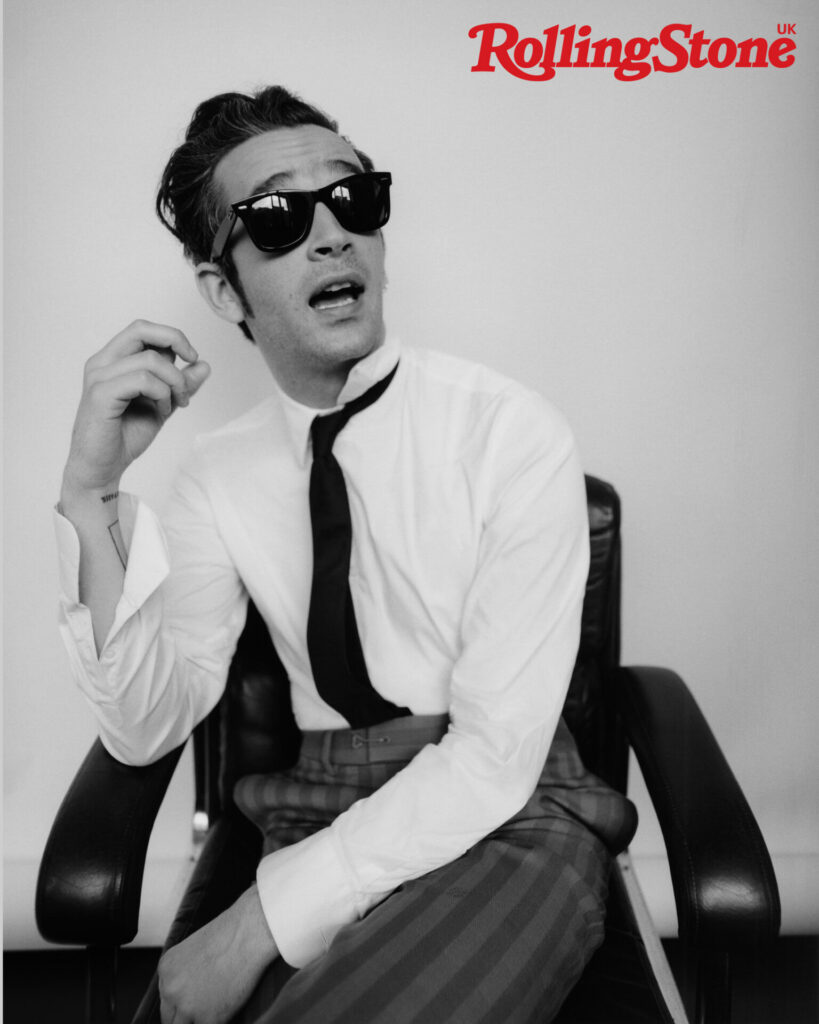

That said, it’s written interviews that are the problem and you can understand his concern around that — you can’t see that I’m laughing at his jokes or that his take, one that looks bolder written down, was prompted by my original question. Now it’s used as the headline: ‘Matty Healy doesn’t believe true love exists any more’, or something. He understands that his vocalism won him a fanbase and critical praise; that it’s what makes him both divisive and interesting as a cultural figure. Hence, he seems nervous the first time we meet at his Rolling Stone UK photoshoot and apprehensive when I’m at his house in north London, although his PR and manager are present. He’s careful to word things with measured exactness, he’s saying things — thoughtful, quite lovely things — off the record and he’s editing his opinions for me out loud. There’s a sense of (perhaps justified) paranoia — at one point in our interview I nudge my phone to check that it’s still recording and he says that he has me covered and nudges his own. His screen lights up and I notice that it’s also recording our conversation.

When I ask him about this the following week, he says he recorded me for three reasons: as a back-up for me if I had a recording problem; because for years a 1975 documentary has been in the making and perhaps the audio could come in useful; to keep a record of our conversation in case he is misconstrued (not that he’d come out on Twitter and say “I have the recording and I actually said this,” he assures me). All concerns lead to the fact that he no longer wants to justify the statements he makes any more. “I won’t be doing any apologies nowadays,” he says. “I’m not apologising for stuff, just because I don’t think you should or I should or anyone should who isn’t a bigot or a racist or violent or a criminal. I don’t believe that I am. So, I just want to make sure there’s context so I don’t have to.”

Anyway, back in his house, Healy says there is so much written information in the world, in the form of captions, tweets, interviews, reviews, that we should look to other forms to communicate with each other. “If you are a person who can convey information, can convey words and ideas, without writing it down you should really do that. Just do that. Try and just do that. I don’t know how many interviews I need from David Byrne. I don’t know how many interviews I would have needed from Velazquez, do you know what I mean? I’m not comparing myself to David Byrne and Velazquez before you wryly smile at me like that…” (I laugh.)

“I’m an addict, which I’ve realised defines all my behaviour. I’m not interested in being clever or being perceived as clever. I’m not a voracious anything”

— Matty Healy, The 1975

It’s new-new media that he’s interested in as a consumer and occasional participant now: Substack newsletters and Dimes Square podcasts like the edgy comedy of Cumtown or culture commentary of Red Scare, though not so much the political content of the latter. He’d like to go on The Joe Rogan Experience — during a two-and-a-half-hour conversation with the controversial American podcaster, he believes he could speak at length on topics without talking points being distorted by edits.

No longer doing interviews made sense when he originally said it. The 1975 was inarguably the most culturally relevant band of the 2010s, making genre-splicing music before that was a cliché because all music is now, and writing extensively about our pervasive internet and social media use. The decade itself had ended as Healy left his 20s, a time of his life characterised by drug abuse, rehab and the extended adolescence of being a rock star. Where to go from there?

Next year, the band will have been making music together in some form for 20 years. Their formation is well documented: classmates Matthew Healy — the first-born child of TV actors Denise Welch and Tim Healy — and drummer George Daniel met at school in Cheshire and became firm friends. They formed various musical projects that resulted in British boy band The 1975, an act that couldn’t get signed by any major label in the world. The endless industry conversations and disappointment left Healy confused. The band and their manager Jamie Oborne decided that they would join Dirty Hit, Oborne’s own indie label that’s now what XL Recordings was to millennials for the Zoomer generation, releasing music by left-field artists like Beabadoobee and Rina Sawayama. With The 1975’s self-titled debut album, they were an immediate success thanks to Tumblr girls and Americans who never experienced 00s British indie and were amazed to hear that accent over bright and jangly, 80s-style songs made by musicians indebted to US emo music. As Oborne tells me, “Sometimes, working with artists, it’s like pushing a fucking rock up a hill and other times it just has its own momentum. I feel like people just connected with something within the band’s DNA and Matthew as the front person. And it just sort of spread.”

The 1975 might break up, Healy told the press in the same interviews he announced were his last. That was true for a moment but not so any more. “There’s always been a lot of ‘will they, won’t they’ with my band. Will they split up? Will they not? Will I get over drugs in order…? And I’ve always leant into that because I like that. I love the drama of it,” he grins from his sofa. “And I think that now I’ve realised, not in a non-sexy way, but The 1975 aren’t going to split up. What happens with The 1975 could be a myriad of things, but splitting up is not really going to happen.”

“I’ve always been aware that I’ve been asking different questions on different records, but they are all questions about: Will you? Can I? Can we?”

— Matty Healy, The 1975

What makes Healy feel comfortable with the idea that The 1975 will always exist as a group of old friends making art is his realisation that he is a writer first and foremost. What he writes are not panoramic magnum opuses like Tolstoy — “again, not comparing myself to Tolstoy” — but snapshots of how he’s feeling in the world at a given time. That takes the pressure off being in his band somehow.

So, here we are ushering in the new era of The 1975, in Matty Healy’s stone home that feels like a Japanese monastery. This is the era — rather than it being self-aggrandising, Healy uses this term because his fans adopted it to refer to chapters of The 1975’s career as they do with other pop stars — of embodying the fact that sincerity is scary, properly this time, rather than just singing and speaking about it. The era of vulnerability at the centre of his art and life. The era of no longer being a spokesperson of a generation. The era of being offline and of being, in general. The era of having fallen in love, for real, and writing a markedly sincere love album. The era of wondering, in love’s aftermath, if true love exists at all, but hoping that it does.

ii.

Once you walk through Healy’s front door, you’re faced with a sculpture that looks like a big boulder in his hallway. “I like really heavy weighted objects because they represent permanence,” he explains, “because I tour so much; when I come back, the first thing I see is this immovable object.”

Like everyone else, he was forced to be stationary by the pandemic. The mania of working on two albums in tandem — writing Notes on a Conditional Form by day and touring A Brief Enquiry into Online Relationships by night — came to an abrupt end. During lockdown he began training in jujutsu every day and reflected on himself and his own behaviour, as we all did. “I’m an addict, which is what I’ve realised defines all my behaviour,” he says. “So, I’m not interested in being clever or being perceived as clever or I’m not a voracious reader. I’m not a voracious anything. I’m an addict.” It wasn’t far into 2020, then, before he started working on demos with Daniel that would become their fifth album.

“As you get a bit older, those postmodern, exciting ideas have to start making way for more traditional values which aren’t that sexy. Responsibility, adulthood”

— Matty Healy, The 1975

Healy realised that The 1975 had taken the idea of being a band in the postmodern internet age far enough. Notes was a sprawling, 22-track, experimental album that reached for emo, UK garage, country, house and ambient music. It was existential, poignant, accomplished, a little self-indulgent and for a listener, honestly, exhausting. “I’m sure there are people that haven’t finished Notes,” Healy admits. For a band who had taken maximalism and experimentalism to such an extreme that it had become its own exoskeleton, The 1975 decided to do the most radical thing they could think of: just be a band again.

“The songs were written, and we went to a studio, and we produced them, and we recorded them. We’ve essentially not done that before, apart from the first album,” explains Healy. “You can try and figure out what I mean without this sounding kind of pretentious or wanky, but it’s kind of doing an impression of The 1975. Because as much as The 1975 has gone everywhere, kids know what The 1975 is, do you know what I mean?” They were no longer being clinical about music, a necessary component of creating the last two records. Some of these songs were recorded in one or two takes. “I’ve always wanted to make something very, very intimate and something that allows you to be witness to a moment,” Healy says.

This intimacy taps into the collective consciousness, though, just as the forms of their previous albums were informed by culture of that year. It’s reflective of oversharing fatigue, opinion fatigue, cynicism fatigue. It’s stripping everything back and living simply, as we were forced to temporarily during the pandemic but, more crucially, that we long for in some elemental way now.

Ten years ago, Healy reflects, hearing a computer-generated noise on a track felt surprising and left you wondering how it was made. Now it doesn’t register because anyone with basic programs can make those noises. “What people can’t do,” he says, counting each of these notables on his fingers, “is know how to use a studio, have been in a band for 20 years, have been writing songs and playing together for 20 years, and be able to go into a room and capture that. Like, hardly anyone can do that.” This album was about returning to basic inarguable craft and skill. “It was about doing what you’re good at. That’s what I think people are really into now,” Healy continues. He uses the example of watching an athlete running a race. “We’re never going to get Christopher Nolan to direct the 100 metres to make it more interesting. Because it’s someone doing something great and you just want to watch them do it. And I feel like we’re getting to this era where we don’t want to dress up quality experiences or quality that much.”

With the aim of distillation, they recorded at Electric Lady in New York and Real World, Peter Gabriel’s studio in Bath. Real World looks not unlike Healy’s home: a lot of stone, natural materials, glass panels and built to include elements of light, air and water. Healy used to have a picture of its control room on his bedroom wall when he was growing up in Manchester. To deepen the approach, Jack Antonoff joined at a later date to co-produce the record with Healy and Daniel. “We had a series of conversations, and one of the things was about ‘macho versus tough’ where we wanted to make something that wasn’t macho, but that felt quite tough and grown up and real,” Healy says of working with Antonoff.

“Regardless of algorithms and Twitter and all this bullshit, the amount of love and the desire to replicate beauty is so potent. It almost doesn’t make sense when the universe is designed towards decay”

— Matty Healy, The 1975

Back when their debut album was gaining traction, Daniel realised that one of the reasons their music was connecting with people was Healy’s ability to make a listener or audience member feel personally addressed. “We really wanted to return to this and purify it on this record,” Daniel writes over email.

The result is being funny in a foreign language. Its 11 tracks, including the usual self-titled ‘state of the nation’ opener they place at the beginning of all their records, make it their shortest album yet. The intention is that you can listen from front to back in one sitting. They’re considering how to tour their being funny live show which will start in America in the autumn of 2022 and in the UK in early 2023. It will be “intimate” — that word again — and the polar opposite of the previous tour, which was in your face, explosive and information-heavy with LED messaging behind the band. “I want people to feel like they’re in a little theatre as opposed to an IMAX because, you know, in an IMAX you can just go to the toilet,” Healy says.

The idea of observing and being present for something has been so central to this project that it seeped through in ways Healy only realised on reflection. “When we’ve looked at all the pictures that were taken for this campaign, every single time we’re looking at the camera we don’t like it. And every photo where something is happening, or you’re a witness to a moment, we’re all going, ‘That’s it!’” he says. “Because that’s what this record is. It’s not didactic.” To him, it’s timeless. It took him five records but here he is with an album that sounds like an album.

iii.

The 1975 is known for capturing the millennial experience, by proxy of social media and living online. But this is a band whose central concern has always been love. On the teenage drama of their debut, Healy is emphatically imploring ‘Love me, love us!’; on later tracks (including one literally called ‘Love Me’), they talk of being loved, and both loving and seeking love in drugs, sex and attention; from Brief Inquiry onwards they more directly explore everything in the current climate obstructing us from achieving and nurturing romantic love.

“I haven’t thought about it like that, as the common denominator being love itself in loads of different pursuits of it, but that is what it is,” Healy says when I tell him this. “I’ve always been aware that I’ve been asking different questions on different records, but they are all questions about: Will you? Can I? Can we?”

This new album is a maturation of Brief Inquiry, which was the result of Healy reading David Foster Wallace and thinking about Wallace’s cure for a cynical culture: sincerity. Now Healy is embodying the writer’s ideals in his music rather than musing on them, and the result is more earnest than anyone might expect.

“I think the record is about striving for all of these quite ephemeral goals: love, happiness, oneness”

— Matty Healy, The 1975

“This record definitely takes those ideas and says, ‘Well, nihilism in your 20s is very sexy, and very cool and well done, and maybe appropriate.’ As you get a little bit older, those postmodern, exciting ideas have to — do — start making way for more traditional values, which aren’t that sexy, which aren’t that hip-shaking. They’re responsibility, adulthood, these kinds of ideas,” Healy says. “What I’m asking on this record in the context of love is, can you find true love, versus all of this irony, all of this postmodernism, all of this… I don’t want to say neoliberalism but versus the internet, versus technology? Can we find true love in a way that we were culturally in pursuit of at the beginning of the 20th century?” Well, can we find true love now? “I don’t know,” he says. “It’s really hard.”

Despite what Healy says, being funny in a foreign language seems to think we can find love, at least for a while. To him, the ability to be funny in a foreign language is the height of sophistication. It means you must have empathy and the will to be vulnerable and human by taking the risk of getting it wrong. “I think the record is about striving for all of these quite ephemeral goals: love, happiness, oneness,” he says.

Musically and tonally, being funny is split in two: it starts as outward-looking, wry and analytical about finding love during the culture wars and becomes simplistic and clearly diaristic about his own romantic relationships. “I wanted to write about the culture war but also write about being in love and ‘Yeah, fuck all that, let’s kiss’ or shit that’s a bit cringe,” Healy tells me. “Because I’m so bored of ‘That’s a really good take, bro.’ Like, try saying something nice. It’s really fucking hard.”

A problem facing love at large is the idea that modern masculinity is in crisis. Mass shootings and violence appear on ‘Looking for Somebody to Love’, a dark and upbeat 80s-inspired song that could soundtrack a Black Mirror episode about what happens when a man can’t convince a woman to date him. “You’ve gotta show me how to push, if you don’t want a shove are the words of a young man, already damned, looking for somebody to love,” Healy sings. The lighter side of a confused masculinity is echoed on the lead single, ‘Part of the Band’: “I like my men like I like my coffee/Full of soy milk and so sweet it won’t offend anybody”.

When we come to the topic of men, Healy calls for Oborne to spot him. “What do you need me to spot?” asks Oborne from the kitchen. “Just anything I say that’s ridiculous,” calls Healy, as he opens an enormous cigarette holder, and then to me: “This is a prop from a video, it’s not how I hold my cigarettes.”

“I wanted to write about the culture war but also write about being in love and ‘Yeah, fuck all that, let’s kiss’ or shit that’s a bit cringe”

— Matty Healy, The 1975

We talk about the fact that we have violence and dangerous unchecked masculinity on the one hand and men full of soy milk and inoffensively bland on the other. What is a healthy demonstration of masculinity when young men are being radicalised into anti-feminist communities at an alarming rate? “I do know that the right wing is more successful with the acquiring of young men than the left is, and as somebody who’s definitely on the left, it’s interesting to watch, because the left don’t seem to have [an] ideal masculinity, whereas the right have a very, very easy one,” Healy says.

What grips the imaginations of these young men is a clear directive of traditional patriarchal ideals in the absence of anything else. Meanwhile, in mainstream pop culture, privileged men are praised by their stans, social media users and aggregate websites for wearing dresses, skirts or nail polish —empty signifiers when paired with a celebrity not speaking out on political issues related to gender and sexuality. “What is being a man for men who ‘being a man’ isn’t some meta-performance piece about deconstruction?” asks Healy. “The only form of masculinity that is celebrated is one that deconstructs it. So: in a dress. I don’t know what it is to be a man if you’re not just deconstructing being a man and having that celebrated.”

So far, so 1975. When the album becomes “soppy” and “goo-prone” and straightforward, it’s surprising. Even Healy finds his songs so un-cynical that he almost winces hearing them in the context of the full album. On ‘All I Need to Hear’, a quiet ballad with an electric guitar, piano and strings, he sings to the love of his life: “tell me you love me, ’cos that’s all that I need to hear”. The conclusion on the final country-inspired track (‘When We Are Together’) is that, “the only time I feel it might get better is when we are together”.

It’s not sanitised romance in these latter songs, though; there’s some faded glamour and peaceful realism to the everyday anecdotes. “Everyone is disappointing once you get to know them. Me included, life included,” Healy says, quoting Charlie Kaufman’s film, Synecdoche New York. “Romantic relationships are the one thing that I don’t think Einstein could have ever written a thesis on that would have helped anybody. It’s so difficult.”

I ask him if he’s read the heteronormative and slightly outdated book The Art of Loving by Erich Fromm, one of my favourites about relationships. He hasn’t, so I explain its general thesis: that love is not a feeling but something to practise, requiring discipline, commitment and attention. “Maybe they just had a really rough bird and they just had to write this book,” Healy says. He performs amusingly as Fromm: “‘No, it’ll be fine. It’ll be fine. She’s nice. She’s nice.’”

“Everyone is disappointing once you get to know them. Me included, life included”

— Matty Healy, The 1975

He’s joking but agrees with Fromm in theory: love is about maintenance and commitment. As he typically does, Healy brings this idea back to music. “Inspiration doesn’t come looking for you. Love doesn’t come looking for you. You have to turn up every day and catch it,” he says. “I’ll go to the studio and it’ll be dull for four hours. It’ll be the same keyboard sound, the same keyboard sound, but then accidentally someone knocks an oscillator and it does something interesting. And I go, ‘Oh, what’s that?’ And now you’re off and you’re creative, and you’re alive. So, it’s about turning up every day and allowing it to happen. Because if you don’t turn up, nothing’s gonna happen.”

Above Healy’s head as he speaks is a black square canvas affixed to the wall. It’s his favourite painting in the world, by a man called Hisashi Indo. “He was a civil engineer who missed the train to Hiroshima and all his mates went and the bomb went off,” Healy explains. “He didn’t know how to deal with that experience. And he didn’t want to be a civil engineer any more, so he would, in his back garden every day, in this symbolic ritual, use this deep-purple lacquer. He’d do one screen print over and he would do that every day for a year. Eventually, it just turns black. After a year of just one action that is a representation of his grief, it becomes a metaphor of a painting. Because it isn’t a painting, but it fucking is. So it’s a paradox and it comes from… well, fucking hell, where does that come from?”

iv.

Matty Healy has something called The Room in his house. It’s filled with oddities from a storage container that he’s not got around to organising yet. The reason he let me see inside the “nightmare” is because he mentioned he had some esoterica that’s “pretty fucking out-there” and obviously I needed to see it. He gives me a hand as I hesitate in stepping over the miscellaneous items that cover the floor. There’s enough chaos to feel almost embarrassed to look in front of the person who created it, but if they weren’t there, you’d be like a PhD student at the British Library, poring through its contents for hours.

To list some of Healy’s cultural artefacts explains his world view — and at the very least, it’s a nod to the many Easter eggs he leaves hidden in his work, ones that The 1975 fans successfully uncover with each release. He has Daniel Johnston original cassettes; a poem by Jack Kerouac on the poet Arthur Rimbaud, who is name-checked in ‘Part of the Band’ (“raunchy stuff in here as well,” he comments, pointing to some lines); a William Burroughs shotgun art arrest card; a postcard that was sent to fans of industrial music pioneers Throbbing Gristle in 1981 to inform them of their break-up.

My favourite is his original press release for Infinite Jest,tucked inside a copy of Wallace’s short-story collection, Brief Interviews with Hideous Men. I tell him that reading the story ‘On His Deathbed’, in which a man describes the son he has always hated and the son’s mother who was “reduced and remade” by the boy, nearly put me off having kids for life. “There are so many films or pieces of literature that fucking just terrified me about real life,” Healy says. He wants kids, at some point: “I’m all right, I’ll be fine. It’s about money, really, babies, isn’t it?”

“Inspiration doesn’t come looking for you. Love doesn’t come looking for you. You have to turn up every day and catch it”

— Matty Healy, The 1975

One of his favourite items is a pamphlet from the 60s by activist Abbie Hoffman called Fuck the System. It details how to live outside the law in New York: how to get free food, accommodation, lawyers, drugs. Healy was a teenage punk, influenced by the fact his dad came from a mining community devastated by Thatcher’s leadership. “The ethos of punk would be so demonised by the left if the Sex Pistols or something legit like that happened right now,” he says, holding the pink pamphlet in both hands. “When I reflect on all of these things that I’ve collected since I was a kid, that for me have represented true counterculture and progression, I feel a bit politically homeless, because I don’t know how those things would be embraced.”

I suppose there’s a question that some reading this will be wondering about. “What I’m not moving into is my ‘anti-woke’ era,” Healy assures me. Never has he tried to maintain a good liberal position because it’s popular to do so, he says, though that has been assumed by detractors in the past few years. “What did I do?” he says, counting each statement on his fingers again: I said, be nice to gay people, be nice to Black people, let’s save the planet and organised religion is a net bad.

He brings up Twitter, which he says he left in 2020 because he wanted to comment on the culture war, not be a part of it (“I’m not representative of anything political,” he remarks). Though he continues to embrace YouTube and learning online, phones and social media are generally regarded as a burden. If you want a relatable moment in this profile, it’s this: at one point, he looks out to the Japanese garden that’s exposed to the sky and says, “I’m getting a raven, mate. Write with a quill, send it out there.”

What these sorts of often-repetitive minor “cancellations” mean for artists like Healy is ambiguous (he left Twitter but is frontman of the biggest cult band in the world and co-creator of one of the most anticipated releases of the year). Rather than have tangible impacts on their careers, it would appear that these micro-dramas mostly cause artists anxiety and stress. Healy, the king of being soft-cancelled, is now someone young musicians reach out to when they experience a public scolding. “I’ve almost got this big brother — not Orwellian, actual big brother — relationship with them because I am one of their peers,” he says, adding that, “My phone’s like Samaritans if you’re getting cancelled.” He realised on reflection that on being funny, there’s more cancellation content than he’d intended. “I think there’s three lines about being cancelled, and I’ve started thinking, ‘Fuck, I don’t really care that much about the cancelling.’ I’m not worried about that; it’s just a funny thing,” he says.

It’s increasingly hard to care about the smaller moral slights made by public figures when the larger ones by people with legislative power are so egregious and unpunished. We have a need for bad guys online, Healy believes, because we are all the main character, performing for our audiences, and main characters are nearly always inherently good.

“I’ve almost got this big brother relationship with [other musicians]. My phone’s like Samaritans if you’re getting cancelled”

— Matty Healy, The 1975

“I probably couldn’t even give you an example right now [who] one of those bad guys in the past year is because we don’t care,” Healy says. “Whatever morally impassé thing this person has done, we genuinely don’t care about it. All we really want to do is perform our goodness.” He uses the recent news story about the musician Lizzo using an ableist slur in a new track and the discourse around that as an example. “Nobody was sat at home with their partner coming over to them going ‘Babe, you OK?’ And them going, ‘…It’s just this Lizzo thing.’ You know, that’s never happened. It doesn’t happen. People don’t care like that. And we shouldn’t pretend that we can have the ability to care about everything.” There’s probably a bad faith reading of what he’s said, stripped of context and without me agreeing and smiling while thinking about the ‘babe, you OK’ meme, but he’s not wrong.

What we do actually care about, Healy says, is love. It is the people in our lives, the ways they emotionally move us, the person we come home to every night.

v.

The following week, Matty Healy is born again. He’s softer and composed over a video call when he shows me that he’s on the sofa underneath the grief art, exactly as he was before. He doesn’t couch his phrasing in stage directions. There’s no one to spot him.

He’s spent the time since we met thinking about how being “Daddy Healy” on tour will be tough. “When I was, like, 24, 25, everything I did was so fuelled by the bloom of youth, and I don’t say that to make myself sound old, but I used to not put a lot of work into what I did and everything I did naturally,” he says of performing on tour. “And now everything I do is… well, I mean, look at my breakfast.” He holds up a meal fit for Pingu: a fish on a white plate, nothing more.

Now we’re edging closer to the release of being funny, how does he feel about the prospect of releasing something more vulnerable and personally exposing? There’s a gear shift as he eats the mackerel. “Good! Yeah, too fucking right! I mean, I’m not scared any more, do you know what I mean?” he says, and pauses after a faintly performative mouthful. “Like, well, hold on… Why am I saying that, so, like, aggy?” I had noticed, too. Maybe because you are scared, I offer. He claims he just hadn’t thought about it yet — and did I really think it’s more vulnerable than his previous work?

“I’ve realised that that [love] is as beautiful and rewarding if you’re mindful, if you’re not in search of all loves at once”

— Matty Healy, The 1975

It is — I point to the 2018 ballad ‘Be My Mistake’, an unguarded acoustic song about cheating and finding comfort in sex and love. It could happily exist on this album but stuck out as different on Brief Inquiry. He agrees, which is comforting to him because ‘Be My Mistake’ doesn’t make him feel vulnerable but connected. Someone once told him to read the comment section of that song’s video: it’s like a Reddit thread of people no longer talking about the song itself but about their experiences of cheating, love and loss. “It’s the one thing that makes me as religious as I’ll allow myself to get comfortable with,” he says of this and of our impulse to connect through art. “There’s just too much love in everything. Regardless of algorithms and Twitter and all this bullshit that we talk about, the amount of love and the desire to replicate beauty is so potent. It almost doesn’t make sense when the universe is designed towards decay.”

In our previous conversation, Healy was uncertain if true love exists, but here he is, I say, talking about the communal love we all experience through music, regardless of the presence of romantic love in our lives. Isn’t that true love, too?

“100 per cent,” Healy says. “Sometimes you can stand on stage in front of 10,000 people, and not in your life at that time have a potent individual love. You don’t have a partner — which everyone wants, especially at night, which is coming in an hour, in the hotel room by myself. Someone shouts, ‘I love you, Matty’ and your heart goes, ‘No, you don’t.’ And you almost resent the crowd in front of you. And that’s that thing that you do in your 20s because you’re romantic and everything’s about your boyfriend or your girlfriend. It doesn’t matter if there’s 10,000 people there. I’ve realised that that [love] is as beautiful and rewarding if you’re mindful, if you’re not in search of all loves at once. I’ve had to stop being in search of all drugs at once, all experience at once, all love at once.”

He’s had two years of practising restraint during the pandemic and had just started to get better at existing in the moment on stage last year. “I think what I’m talking about is just not taking things for granted any more,” he continues. “Because, like you say, the pandemic or this newfound connection with each other, is this realisation of what true love is.”

“[This is the era of] appreciating everything in that room instead of intoxicating myself, overreaching emotionally for everything”

— Matty Healy, The 1975

So, this is the era of valuing every face in the crowd; the era of “appreciating everything in that room instead of intoxicating myself, overreaching emotionally for everything”.

“If I have that in my mind — let’s get the love going in a non-hippie dippie way — I think that’d be a really nice era for The 1975,” Healy concludes. He notes the simple way the band decided to relaunch their socials and start to tease new material. “I’m still making jokes, but we were like, ‘What are we going to say? We’re not going to say something fucking dry. And we’re not going to do something abstract and “cool”.’ We’re gonna fucking be like: ‘Hey, guys. Thank you so much. How fun is it to do this? We love you.’”

The 1975’s new album Being Funny in a Foreign Language is out 14 October 2022.

Taken from the August/September 2022 issue of Rolling Stone UK. Buy it online here. On UK newsstands from Thursday 14 July.

Photography: Samuel Bradley

Fashion direction: Joseph Kocharian

Styling: Patricia Villirillo

Makeup: Elaine Lynskey

Hair: Matt Mulhall c/o Paula Jenner @ Streeters

Photo Assistant: Stephen Elwyn Smith

Styling Assistants: Nelima Odhiambo & Rafaela Roncete

Lighting Assistants: Kiran Mane & Emilio Garfath

Studio Assistant: Oak McMahon