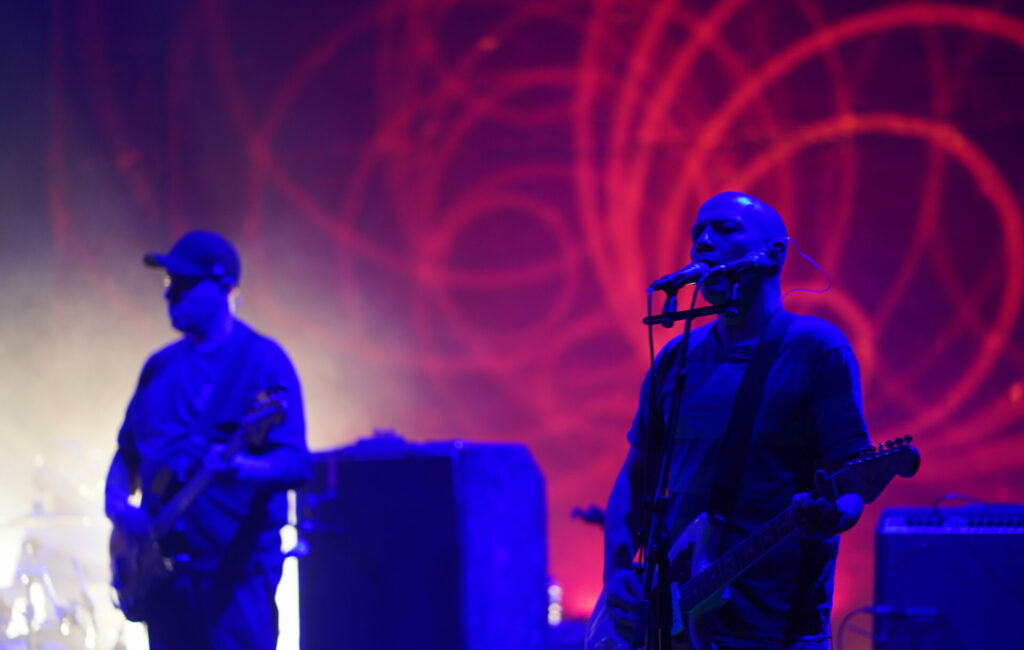

Sound of the Chemikal Underground: Mogwai & The Delgados in conversation

The reformed Delgados talk with Stuart Braithwaite of Mogwai on Glasgow, running a record label and their decades-long friendship

By Joe Goggins

“By the time we were all hanging out at The 13th Note, there were so many bands, but no two of them sounded alike.”

Mogwai and The Delgados have never made for obvious musical bedfellows, with the former eardrum-shredding titans of post-rock and the latter master purveyors of quick-witted melodic indie. Their careers, too, have followed markedly different paths; while Stuart Braithwaite’s group are continuing to surprise as they close in on three unbroken decades together – scoring their first UK number one album in 2021 – The Delgados’ story was one that looked closed after they split in 2005. Last month, they turned back the clock as they finally headed back out on the road for their first shows in 17 years.

In reality, though, their journeys have been intertwined from the beginning. As Delgados singer Emma Pollock tells it, their drummer, Paul Savage, produced some of Mogwai’s earliest sessions in the mid-nineties, close to their native Glasgow in nearby Blantyre. “Hamilton!” interjects Braithwaite, as he joins Pollock, Savage and Rolling Stone UK on a Zoom call. “It was in Hamilton. Let’s not get Lanarkshire wrong!”

Mogwai were signed to The Delgados’ own Chemikal Underground label in time for 1997 debut Mogwai Young Team, which was reissued on vinyl earlier this month along with its 1999 Chemikal follow-up, Come On Die Young. In the years since, they’ve set up their own influential label, Rock Action, while Chemikal has become a byword for Glasgow indie, a monument to the diversity and independence of the city’s alternative scene.

Not bad for a venture that began in 1994 as a way for The Delgados to get their first 7-inch into UK record shops; a two-year internship at the management company for such Scottish pop giants of the time as Texas and Deacon Blue had convinced Pollock to do things her own way. “I was a pain in their arse, because I was a only interested in giving them compilations of all the indie bands I was listening to at the time! I don’t think they could wait to get shot of me.”

“But there was a pivot, at some point in the nineties, where Scottish musicians began to question if they needed to go down the road of moving to London and chasing a pop career, because it involved giving up so much control. When we started Chemikal, we were buying ourselves some artistic freedom, and the opportunity to have a career that would last longer than the plans for a bigger label’s financial year. Mogwai are an absolute testament to that.”

As Braithwaite puts it, Chemikal did for Glasgow what Factory did for Manchester, “because it showed bands they didn’t need to move to London – you could stay where you were. It seems farcical to say it now, because you pretty much have to be an oligarch to live in London these days, but for years, you were expected to move there if you wanted to make a career out of music. I haven’t heard that said for years, and labels like Chemikal are a part of why.”

Inspired, too, by Glasgow indie forefathers Postcard Records – whose founder, Alan Horne, scrawled down what Savage describes as “a blueprint for how to start a DIY label” when Pollock cornered him one day during her internship – The Delgados started Chemikal at a moment when Glasgow’s indie scene was emerging from the long shadow of Teenage Fanclub. “It was very eclectic,” Braithwaite remembers. “I can’t think of many bands that sounded like The Delgados, or us – it was a scene where people were proud of, and striving towards, sound like themselves, rather than anybody else. It was healthy, and not something that was very common.”

“Plus,” adds Pollock, “I don’t know if reaction is too strong a word, but, there was a sense that Britpop was in full swing, and that it was something we weren’t interested in assimilating with. The Scottish scene had much more in common with North American college rock at the time, bands like Pavement and Sebadoh. We were looking towards something that was a bit rawer, and more guitar-led…”

“…and a little less corporate,” quips Braithwaite. “A lot of bands were putting out their own records at that time; Urusei Yatsura did a split 7-inch with The Blisters, which Alex Kapranos put out, years before Franz Ferdinand. Then there was Vesuvius Records, releasing The Yummy Fur’s stuff, and we started Rock Action for the same reason, just to put out things that nobody else would. The difference was Chemikal was that they always wanted to be a record label, rather than just release a single and have a party. They had a different outlook.”

By Savage’s recollection, the launch of Chemikal was partly out of necessity, with a deal that The Delgados had lined up with another label ultimately scuppered by a disastrous gig at the In the City industry showcase in Manchester, where they unwittingly tuned up with a tuner that was a semitone off and duly delivered “the gig of nightmares, in front of an audience of industry guys who were there with their arms folded, shouting, “get off, you fucking amateurs! The deal disintegrated in front of our eyes.” Still, the launch of their own label would help shape the careers not only of themselves and Mogwai, but the likes of Arab Strap, Bis, The Phantom Band and revered CHVRCHES forebears Aerogramme.

Now, with a reformed Delgados back on stage together, Chemikal continues to go strong, even after what Pollock describes as “a bit of a reshuffle” as they grapple with a massively changed industry landscape. “You have to choose your battles now,” she reflects. “Everything’s more expensive, and there’s less income from the ground up. You have to really think about what you can afford to be involved with, and I know that if we didn’t start when we did, and have the catalogue that we do, the label would have a very different character. It would be a hobby, for most folks.”

Braithwaite, who continues to release albums by the likes of The Twilight Sad and Kathryn Joseph on Rock Action, agrees that the environment is tougher than ever for those not already established. “I’m not complaining for myself; we’re doing alright. But for the next Mogwai, or the next Delgados, it’s obviously a lot harder. More people are listening to music than ever, and I was looking out at the crowds on the shows we’ve been playing recently; I’m pretty sure a lot of the people there weren’t born when we released Young Team. Something needs to happen to support new artists, to make it sustainable. It’s not enough to say, “streaming doesn’t pay, so we should stop that.” It’s too late, that genie is not going back in the bottle.”

He’s more upbeat, though, on Glasgow’s future as a music city, which he credits to the legacy of Chemikal. “I don’t think it’s changed too much, but what has happened as the years have gone by is that people started to move here to make music. A lot of great musicians grew up here, but on the back of what The Delgados and Franz Ferdinand and Belle & Sebastian did, kids started coming to uni here to start a band, or be a DJ, or a singer, or whatever.”

Savage concurs. “There was a moment in the mid-nineties when bands started to realise you didn’t need to sound like anybody else, and the spirit of that lives on; you can hang out together, you can share your resources, but ultimately, everybody has a sense of identity and individualism.”

Mogwai’s Young Team and Come On Die Young are available on reissued vinyl now. The Delgados play Glasgow’s Kelvingrove Bandstand on August 12