Burna Boy: Rise of the African Superstar

In his first interview after a brief, self-imposed break and with new music on the horizon, Burna Boy reintroduces himself as the complex character he has always been

I might decide to not drop an album for a long time. In fact, you know what, no album till further notice,” read the September 2021 Instagram story from the man who had spent the previous three years lining the charts with singles. The announcement, though disappointing, was almost expected. But six months after confirming his full-length absence, Burna Boy’s album mode has been reactivated.

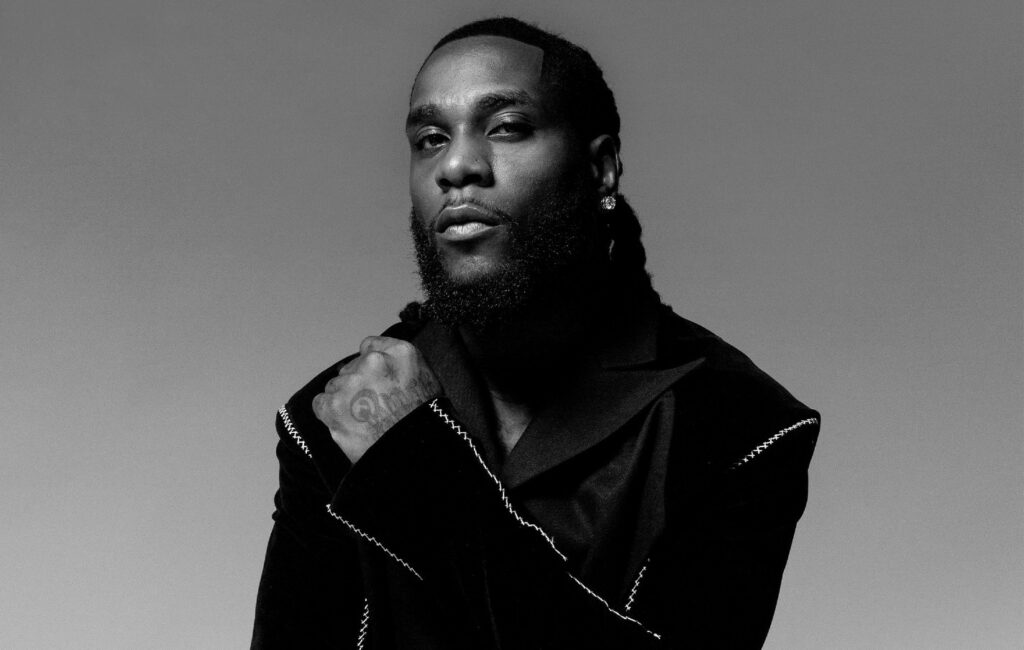

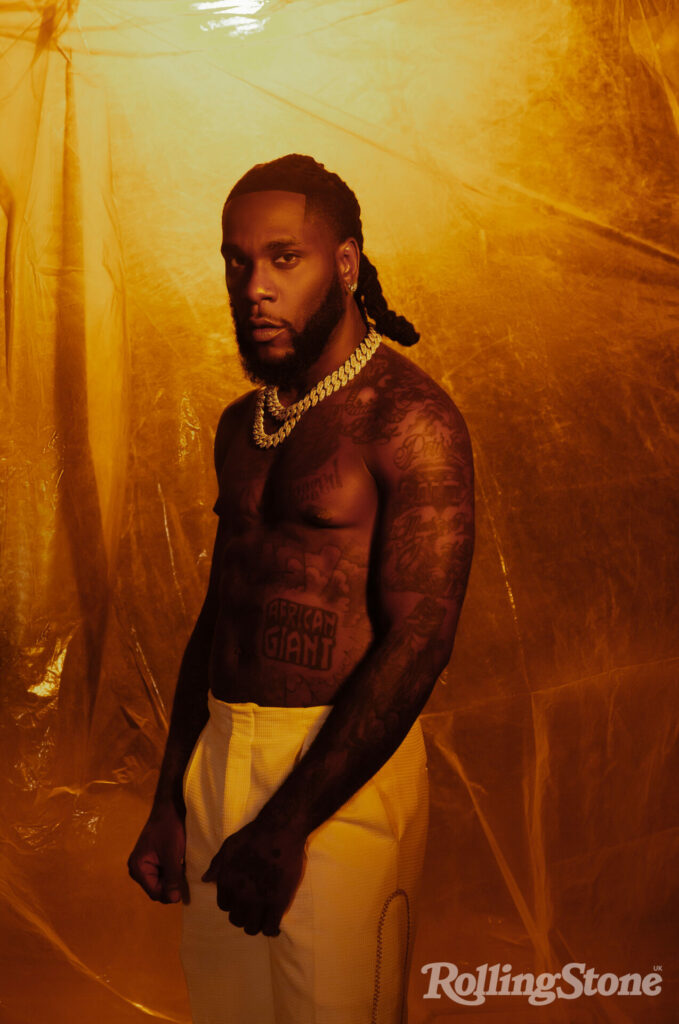

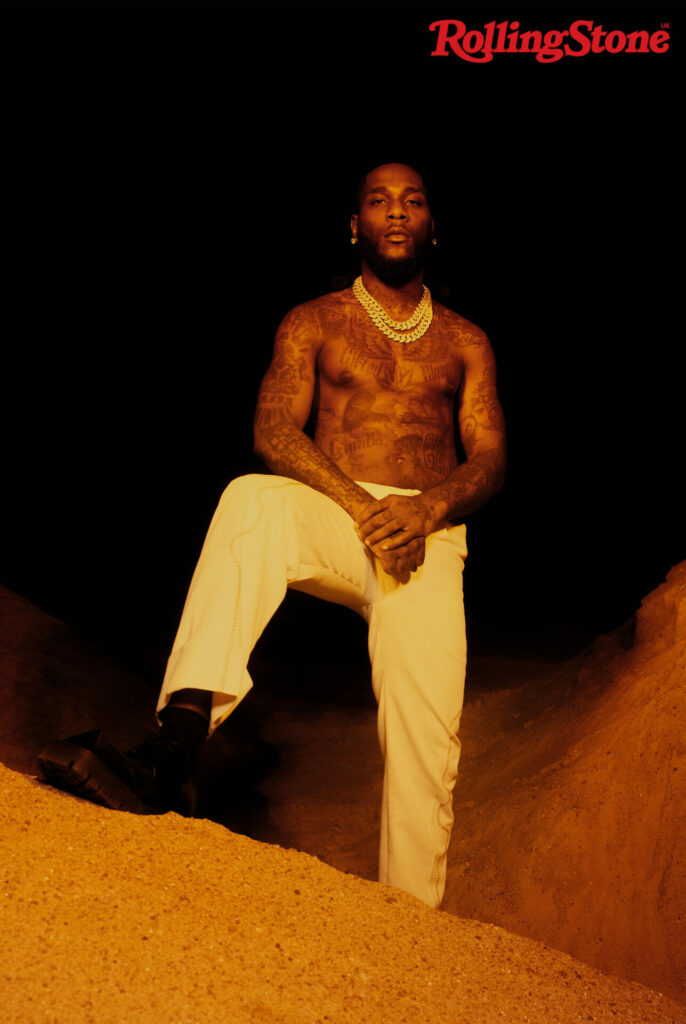

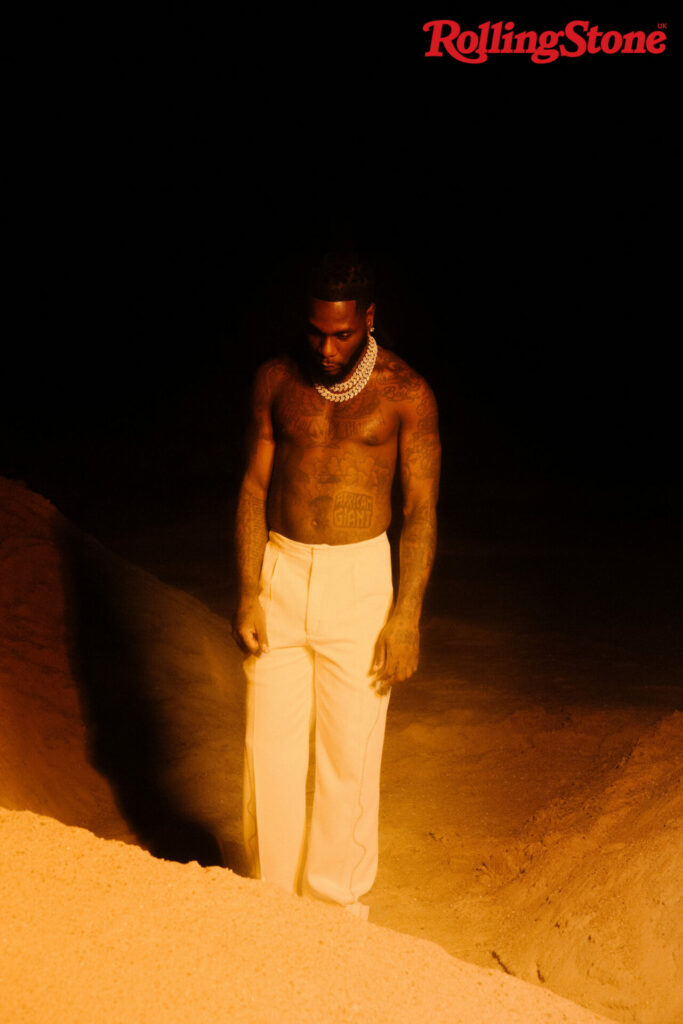

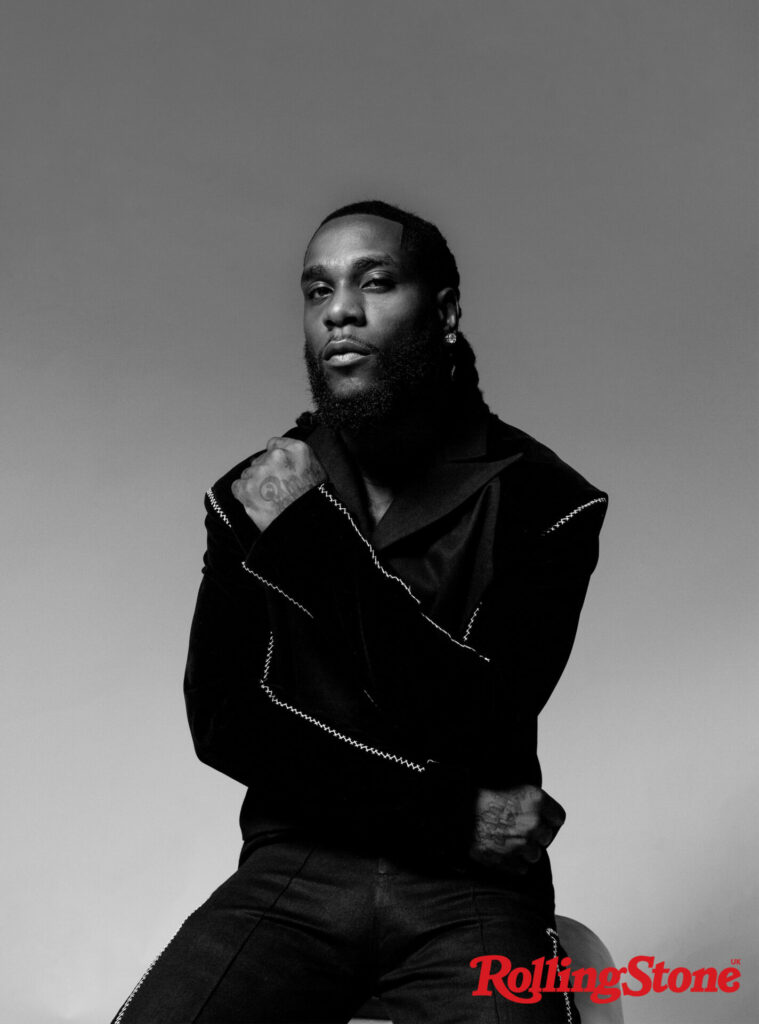

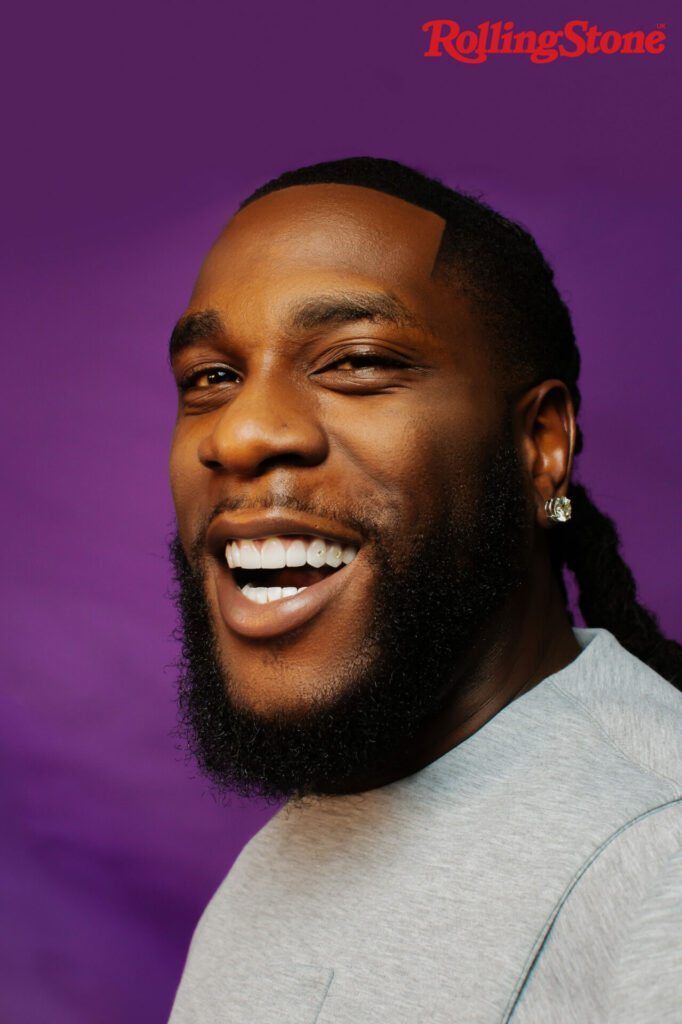

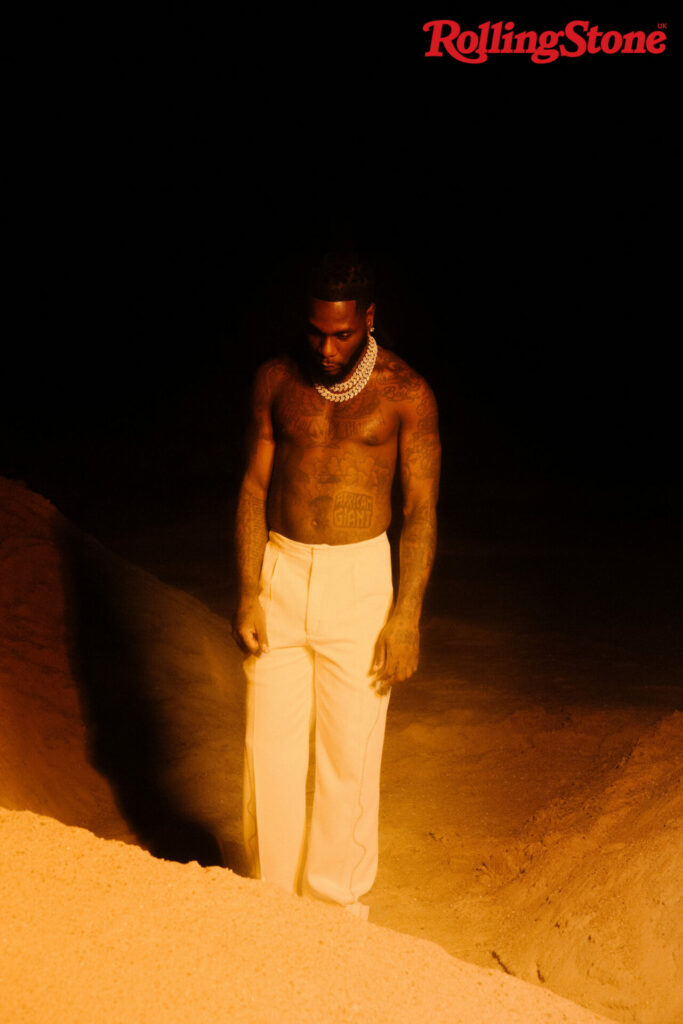

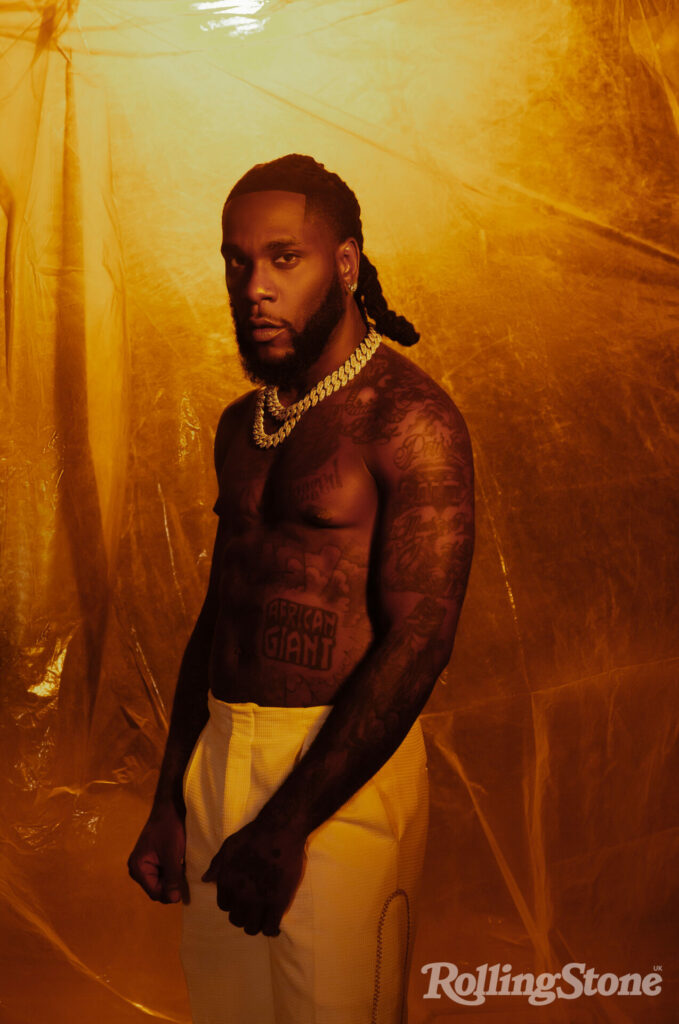

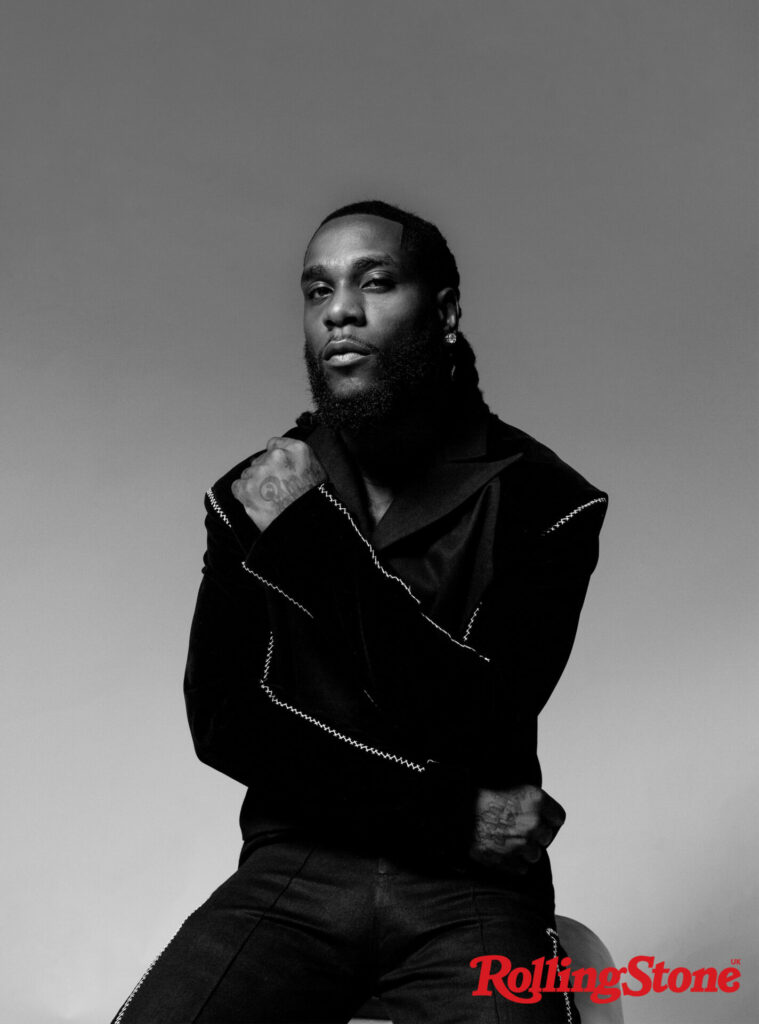

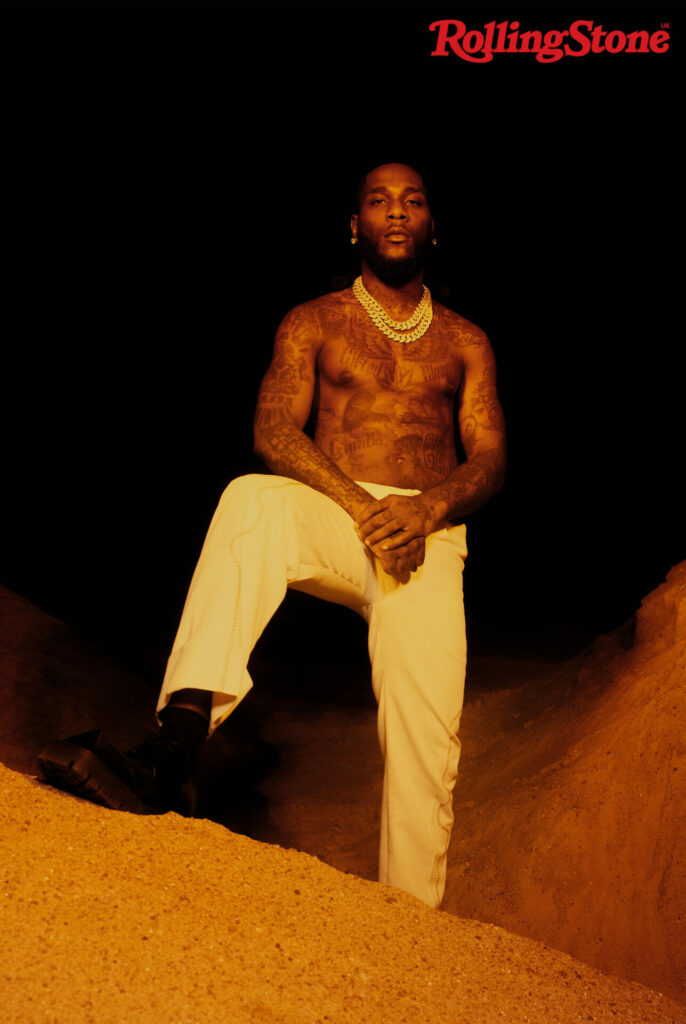

Burna Boy poses for Rolling Stone UK (Picture: Daniel Obasi).

Burna Boy poses for Rolling Stone UK (Picture: Daniel Obasi).

Burna Boy poses for Rolling Stone UK (Picture: Daniel Obasi).

Burna Boy poses for Rolling Stone UK (Picture: Daniel Obasi).

Burna Boy poses for Rolling Stone UK (Picture: Daniel Obasi).

Burna Boy poses for Rolling Stone UK (Picture: Daniel Obasi).

Burna Boy poses for Rolling Stone UK (Picture: Daniel Obasi).

Burna Boy poses for Rolling Stone UK (Picture: Daniel Obasi).

Burna Boy poses for Rolling Stone UK (Picture: Daniel Obasi).

I’ve been on a Zoom call for almost an hour, patiently waiting for Burna Boy — the 30-year-old Damini Ogulu — to appear. When a baritone “hello” comes, I’m surprised: I’ve been trying to pin down the Nigerian Afrobeats star all week. It’s our fourth attempt to speak after the previous three were rescheduled — never mind his Rolling Stone UK photo shoot that began in Lagos, relocated to London, and then, at the 11th hour, shifted back to Lagos so that Burna Boy could carry out reshoots for the video of his new single.

I’ve been briefed that Burna Boy is not in a good mood. I have also been instructed not to talk about cars, relationships or to make any comparisons to other artists. But I do have the green light to talk about his pets and the music. I lead with the latter — and quickly realise my error.

“You don’t know that!” Burna Boy challenges me when I ask about a forthcoming new album, his tone warning that “album mode” means he’s cooking. As Burna Boy repeats, you don’t know his plans. He’s confident in that because he doesn’t even know his plans. When I bring up the new single — which I am assured will be public knowledge by the time you read this — Burna Boy is equally as incredulous in his response, asking me, “Which single?” before he is cut off by his public relations manager. With the microphone on mute, she explains to Burna Boy the larger team’s plans, which include the imminent release of a new single.

“Yeah, so the new single,” Burna Boy says with a laugh that assuages my fear that my question would lead to yet another rescheduling. He continues: “I’m just trying to be positive and have fun with it, you know?”

Each album has served a different purpose for Burna Boy. On his 2013 debut, L.I.F.E, it’s in the title. Leaving an Impact For Eternity was a projection of his legacy before he had even begun. The opening track of the record introduced us to the emerging artist through the now-infamous melody “They call me, they call me, they call me Burna Boy,” as a female voice states the purpose of the whole tape, singing: “it’s my life, my life”. The largely triumphant project featured the Afropop stars of that generation: M.I Abaga, Olamide, Wizkid and Tuface (now 2Baba) and, more importantly, set Burna Boy up as the newest sensation on the scene.

L.I.F.E’s 2015 successor, On a Spaceship, is markedly more chaotic. We learned of the nascent artist’s bad-boy reputation. “You can’t have all that and have a peaceful career,” Osagz, the controversial Nigerian media executive, proclaims on ‘Intro’. More recently, Burna Boy’s tirades — such as the immortalised ‘African Giant’ rant in retaliation to his small font billing on the 2019 Coachella lineup; his relentless repetition of his dubitable grass-to-grace story; and his political virtue-signalling through claiming to be the best thing since Fela Anikulapo-Kuti, arguably Nigeria’s most politically conscious musician — are interpreted with some level of virtue, their largely Afrocentric messaging earning interest from progressive media including Apple Music’s The Ebro Show, NME, The Fader and the Evening Standard.

“I don’t feel comfortable with my life in people’s hands — and that means anybody, including the family”

Burna Boy’s feuds are quickly discarded in favour of the ‘passionate advocate for Black pride and empowerment’ narrative that positive interpretations of his outspoken nature would invite.

After being almost boastful of his bad-boy status in On a Spaceship, he sought redemption on the album of the same name just a year later. But the rehabilitation of the Burna Boy image didn’t really begin until the 2018 release of his third studio album, Outside. It’s full of personal revelations. The bouncy memoir, ‘Ph City Vibration’, details the life and times of the “Port Harcourt original”, referencing his Nigerian home city, while on the electronic album closer, ‘Outside’ featuring Mabel, he expresses his feelings of isolation. Rejecting his reputation as Nigeria’s most talented troublemaker, this was his most successful attempt at speaking exclusively through the music, a practice that has served him well in the years since.

Since tweeting “Leaving all social media platforms permanently” in May 2019, Burna Boy manages to remain outspoken about his beliefs. Returning to Instagram and Twitter from time to time, his outbursts are less frequent, but he’d sooner hang up his cape than conform to the popular expectation for artists to strive for palatability. Take it or leave it, Burna Boy is who he is. Nobody can tell him who to be or what to do — a fact I was lucky to have grasped as a fan, before he would show up a week late to interview. His UK PR, his management, even his label (whose money he keeps so he can return it if they ever “act up”) have no dictate over Burna Boy. As he explained in the first ever issue of Nigerian music and culture publication, The NATIVE, in 2016, “enito mo’na ni”; Burna Boy knows his way. His way.

On Outside, Burna Boy showed that he had grown into a significantly more measured and mature artist, possibly thanks to his mother, Bose Ogulu, formally assuming the role of his manager the year before.

Family members are crucial cogs in the Burna Boy machine. With his sister, Ronami, as creative director, and his other sibling, Nissi, enjoying her brother’s spoils, which he often uses to promote her music, art and other creative endeavours, Burna Boy easily meets the traditional Nigerian expectation for the eldest son to provide for his family.

“The hardest thing I’ve heard in my life was Mark Morrison’s song ‘Innocent Man’. That’s the first thing that ever made me cry”

“It’s very conscious,” Burna says of his choice to bring his team — literally — in-house. “Those are the only people that I’m comfortable enough with… for me it’s just the safest way. I don’t really feel too comfortable with my life in people’s hands and shit like that — and that means anybody, including the family — but at least with the family it feels a little better,” Burna finishes with a slight chuckle.

Born in 1991, the young Damini Ogulu developed a taste for reggae and dancehall via his father and learned about hip-hop from a young uncle. He was later introduced to R&B by a girl he liked when he was 10, who gave him a CD by American R&B singer, Joe.

But a major influence was found through his grandfather: Benson Idonije was the first manager of Afrobeat pioneer, Fela Kuti, a fact that palpably inspired the eventual Burna Boy, who is often dubbed Fela’s incarnate.

These eclectic childhood discoveries were followed by adolescent ones, many of which were made in the UK. Arriving in England for the first time at the age of 12, it wasn’t until Burna Boy returned for university (his face tells me he was doing anything but studying during that period) that he really discovered his passion for music.

“That’s when my brain was fully formed enough to know,” he explains of his first experience of the UK music scene as a student. A period he’s previously described as his dark era, Burna Boy shies away from speaking about his personal life during that time — he did what he had to do to survive and that’s all we have to know. However, when it comes to his formative music experiences, Burna Boy has fond stories to share. He recalls with a glimmer in his eyes that Mark Morrison was the first UK artist he ever revered. “I liked Mark Morrison most. Plus, he bought me a pair of Air Max’s,” on a random day outside “JD Sports or something”. Reading my age from my searching expression, Burna quickly asks, “Do you know who Mark Morrison is?” “The name is familiar but I can’t tell you a song,” I reply, which cues a smoothly sung cover of ‘Return of the Mack’.

“No!” he exclaims. “The hardest thing I’ve heard in my life was [Mark Morrison’s song] ‘Innocent Man’. You know that’s the first thing that ever made me cry — like, actually cry.”

When he decided to pursue music as a career, Idonije was the first to nurture and encourage his grandson. As a young dreamer, there is no greater co-sign than your grandparent’s approval. As an aspiring artist, having Fela’s former manager believe in you is validation that’s hard to beat: it’s no surprise that Burna Boy came onto the scene cocksure.

“Coming up through being different. Suddenly, it’s now become the way”

Before breaking out with his debut album in 2013, Burna Boy was just entering his twenties when he released the 2012 hit single, ‘Like to Party’. A breezy summer bounce, with an LA- esque pool party video, it defied the sweaty tempos then dominating the Nigerian charts. At that time, music fans only had ears for the crowd-thumping party starters that would soon emerge on Western shores as the steady rising sound and subculture of Afrobeats.

Percussion-laden records — including Davido’s breakout ‘Dami Duro’, ‘Chop My Money’ by P-Square, which scored a feature from Akon, and, most notably, D’Banj’s ‘Oliver Twist’ — typified the appetite of the Nigerian market. These up-tempo, bellowing, mainstream Nigerian hits were slowly seeding African music into the Western zeitgeist.

Burna’s laid-back delivery over fusionist production, on the other hand, remained a niche sound. His unique brand of fusionism constituted a whole new ball game that would, gently, over time, broaden the playing field, influencing a palpably diverse Nigerian music industry.

“Now, we’re seeing a lot of other artists coming up with stuff like [that],” Burna Boy says of Nigerian music’s new dispensation towards more eclectic and diverse production. “Coming up through being different. Suddenly it’s now become the way.”

At first reluctant to “[say] anything that makes [him] feel like [he’s] taking credit again (even though God knows where the credit belongs),” Burna Boy is more than happy to remind me — and readers — that his music has always been left field.

The year 2018 was a defining one in Nigerian — and possibly even African — music. Those 12 months birthed the simultaneous global and local rise of a cohort of musicians that played away from the tastes the country was accustomed to, turning to their own worldly influences instead. Likewise, Burna Boy’s self-defined ‘Afro-Fusion’ sound, a melange of global genres, would finally take off that year, too, in response to the release of Outside.

One of the music subcultures emerging from Lagos was the Alté movement. This loud-and-proud counter-grain culture grew out of a community’s unwavering conviction about doing what they wanted, ignoring the country’s customs in favour of their own self-expression. Led by defiant musical producers and avant-garde fashion tastemakers, Alté is synonymous with freedom — and Burna Boy.

“[Burna Boy] is the father of the Alté movement,” his manager asserts, suggesting that the arrival of Outside that year demanded more accepting ears from Nigerian and African listeners, and ultimately influenced the rise of alternative music from the streets to makeshift bedroom studios.

Burna Boy is unsure about this moniker, however. “That’s what they always used to call me, but I never, like — I never accepted that shit because I didn’t understand what it meant,” Burna admits, through laughter.

Starring ‘Ye’ (his ultimate crossover single received a boost when, later that year, fans searching for Kanye West’s new self-titled project, ye, accidentally stumbled upon the Burna Boy track instead), Outside is often considered to be the start of Burna Boy’s third act. But for the Nigerian music industry, the project, along with other music from the Alté genre, evangelised the diversity of Nigerian music to the world. Suddenly, it was more than just Afropop or Afrobeats coming out of West Africa onto the world stage. Nigerian music, in its totality, was gaining ground. Critically,

audiences are now craving diversity in a way the charts have never seen before.

The rush to amapiano or Kumasi drill — and Burna Boy has delivered defining hits for both genres, including 2020’s ‘Sponono’ with Kabza de Small, DJ Maphorisa and Wizkid, and Black Sherif ’s ‘Second Sermon’ remix last year — indicates the insatiable appetite of the global market. The examples are plentiful: see ‘Emiliana’ singer CKay’s prolific rise on TikTok even before his success in his native Nigeria; Amaarae’s ‘Sad Girlz Luv Money’ doing the same and then inviting its Kali Uchis remix; Drake tapping Tems on Certified Lover Boy’s ‘Fountains’; Beyoncé producing a compilation album with West and South African artists, featuring a Burna Boy solo track. Catalysed by the uptick in diverse production that the Outside year set in motion, these examples illustrate how fans across the globe have found affinity with African music.

“I guess God has a sense of humour,” Burna Boy begins, as he describes the reality of his crossover. Born with near peerless musical talent, into the disadvantage of Nigerian social, economic and political depravation, Burna Boy has marched his way into the world and finally attained a long-sought sense of belonging. He says, “Now I belong to the world… I’m a global citizen, you know?”

‘Father of the Alté movement’ — I didn’t understand what it meant”

Burna has stamps in major venues of the world’s culture capitals: he’s played London’s O2, the Hollywood Bowl and Coachella, and joining the list next month will be the famed Madison Square Garden in New York, who, to Burna’s surprise, “literally told him to pull up,” says his manager.

There’s no denying it: Burna Boy is a world-class artist who has been offered the opportunity to reach his full potential, climbing to heights the stifling Nigerian environment would convince you were impossible to reach. It has shown him that he “wasn’t the only one in that predicament. There are artists that I follow that have had similar predicaments, but in different ways. You know, and they’ve seen me as a source of their inspiration, ’cos if you see that it could happen for me, there’s [a] precedent for us all.”

When Burna Boy released his fourth LP — 2019’s African Giant — he was an artist unconvinced of his responsibility. Gradually, though, Burna is beginning to accept the influence of his position as just that: the African giant. He refuses to compromise his actions due to any sense of obligation, though. If he wavers and ends up contrived or acting out of guilt, “what makes [him] any better than the politicians?”

It might shock you to learn that despite his vocal advocacy for social justice across the world, Burna Boy is decidedly not political. His preoccupation is with the truth and illuminating the ways in which our understanding has been warped by Western hegemony. As Nigerian — and wider African — music finds new audiences, Burna Boy remains an influential voice, not just because he releases African hits for the world to hear, but through the conversations he sparks through his work and his interviews. His specially curated episode on The Ebro Show, featuring music and interview subjects of his choice, was titled ‘Miseducation’ — the name given to the Ogulu family’s educational empowerment foundation for children in Port Harcourt. In the same way, Burna Boy is dedicated to

re-educating his audiences as often as he can. His African Giant song, ‘Another Story’, begins and ends with a clip from Jide Olanrewaju’s documentary, A History of Nigeria.

Elsewhere, he has also platformed the narratives of Nigerian executives with integrity, such as Adebayo Ogunlesi (currently the chairman and managing partner at Global Infrastructure Partners and formerly chief client officer and executive vice chairman of Credit Suisse First Boston), whose name appears in the Twice as Tall single, ‘Wonderful’.

In his interviews Burna Boy continues his teachings by advocating for Black unity in tackling Western dominance and governmental subjugation, both on the continent and in the diaspora, or applauding his fellow African musicians for bringing the continent together through the music, spotlighting pan-African empowerment where our governments are seemingly reluctant to do so themselves.

“There are artists that I follow that have seen me as a source of their inspiration”

When I ask what he would do if he had 24 hours to do whatever he wanted, Burna Boy states that he would change the world for Black people. In Burna Boy’s purge, he would execute a globally coordinated heist on the US and UK treasuries, using this money to fund a series of revolutions across the African continent. “You should not give me that one,” he laughs sinisterly, fully aware of the chaos his get-out-of-jail-free day would cause, but also utterly confident in its end result.

“We’re not doing political questions. None. None whatsoever,” his manager interjects, as I prepare to ask Burna Boy what spurs and motivates his political interests.

He can’t help himself, though: “Do you know who is running for president [in Nigeria]?” he asks, letting out a giant laugh before suggesting we move on.

Quickly scrolling past my list of politically charged questions, I land on the next section: collaborations. “Given Nigeria’s queerphobic laws, were you ever anxious of potential backlash to your collaboration with Sam Smith, a non-binary person?” I ask.

“What’s it my business?” he responds. He cares little for the private lives of his collaborators: it’s all about the music, he reminds me. Burna Boy has been a fan of Sam Smith from as early as ‘Stay with Me’, or the artist’s Naughty Boy feature, ‘La La La’; there’s a debate about which came first.

His manager, who sits beside Burna Boy throughout the interview, assures us it’s ‘La La La’. Burna is convinced it was ‘Stay with Me.’ I silently Google the answer and, of course, the manager is right.

“You do forget sometimes,” she chides. “When I smoke too much weed,” he says. “You know that has nothing to do with it.” Apologising each time, random side conversations between Burna and his manager punctuate our 40-minute chat. They’re a joy to listen to, and reveal the playfulness the artist shares with his closest colleagues and collaborators.

Even when it seems antithetical to have our African Giant preach, in his uncompromising Blackness, of the barbaric injustices of Western civilisations upon African populations next to a white British pop star, such as Coldplay’s Chris Martin, who features on 2020’s ‘Monsters You Made’, or an American production duo, such as DJDS on their standout 2019 track ‘Innocent Man’, Burna Boy easily locates the sweet spot where both artists uplift each other while maintaining their individual authenticity. His collaborations with white acts — the first unexpected link-up of its kind being 2018’s ‘Heaven’s Gate’ with Lily Allen, the hugely successful final single on Outside — are seamless, their organic occurrence coming through in their chart-topping sound.

Although Burna’s lips remain sealed as to the details of his next project, his first single of the year conveys Burna Boy’s new year’s resolution to be happy. “It’s a personal decision that I feel I have to, you know, be [happy],” he says, as we wrap our interview. “It’s not really inspired by anything, just me being tired.”

After losing the first year of the new decade to Covid, and — at the same time — witnessing the brutal injustices meted out against Black people all over the world, including at home in Africa, 2021 was not the year of respite we expected it would be. Although full of highlights for Burna Boy, the lows persisted, and 2022 began with the realisation that peace and joy takes effort, as does happiness. The notion that we must put in the work every day to remain on the up is one that the world is collectively leaning further into. This new era is Burna Boy’s hard-earned arrival at a good place, and his commitment to staying there.