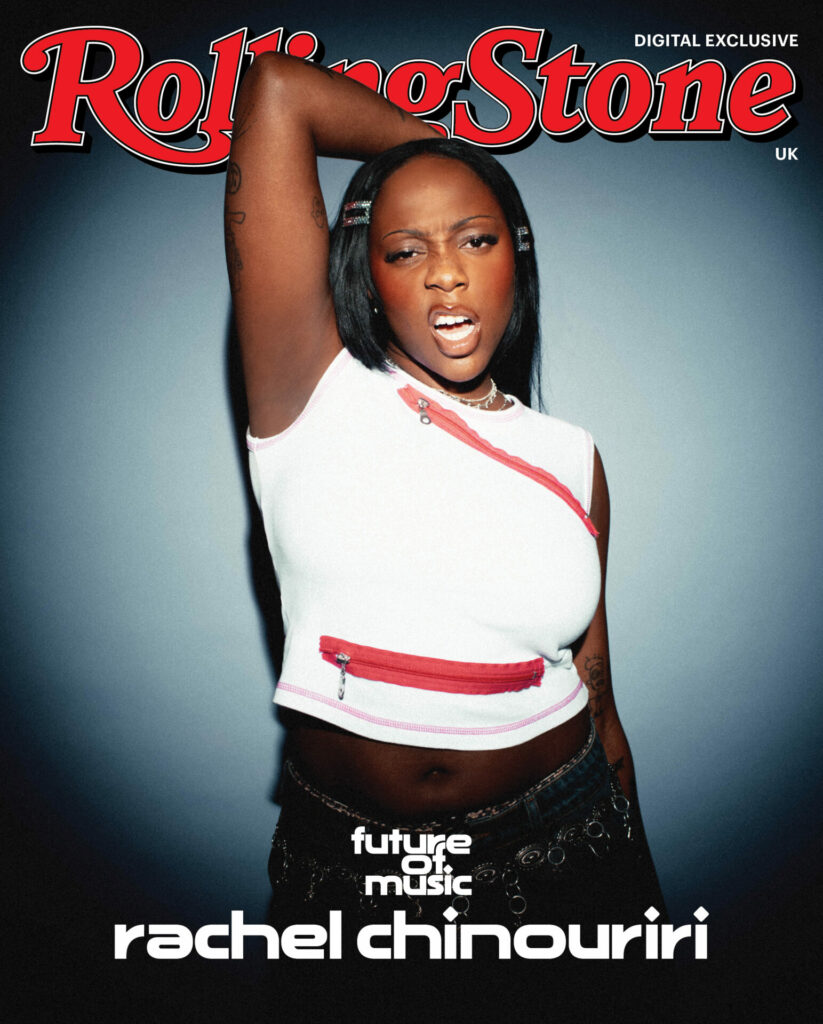

How Rachel Chinouriri changed the narrative to become an indie star

Rachel Chinouriri reflects on her struggle to overcome stereotypes and establish herself as a Black indie artist, as well as the heartbreak that informs her forthcoming debut album

By Nick Reilly

“I want to have a legacy that is set in stone in the future, and I know what I want to represent,” Rachel Chinouriri tells Rolling Stone UK over coffee in an east London café on an uncharacteristically balmy morning in early February. “What I want is to inspire the other 13-year-old Black girls who are confused about their identity but love rock music. I want them to be like, ‘Oh God, it’s possible. It actually exists.’ In 10 years’ time, I’m hoping to look back knowing that my album has been really influential in helping move stepping stones for Black artists.”

It’s the bold manifesto of an artist who already knows what they want to be, and with extremely good reason. When Chinouriri was a teenager, the Londoner had two musical idols: VV Brown and Noisettes singer Shingai Shoniwa, both Black British women who were blazing their own trails within UK indie music.

But when Chinouriri set out on her own path, she was continuously mislabelled as an R&B and soul artist — even though a single listen of her breakout track ‘So My Darling’ is evidence that this couldn’t be further from the truth.

By 2022, Chinouriri had had enough. “My music is not R&B. My music is not soul. My music is not alternative R&B. My music is not neo soul. My music is not jazz. Black artists doing indie is not confusing. You see my colour before you hear my music,” she powerfully wrote on Instagram.

She adds to Rolling Stone UK: “I remember people putting Black squares on their Instagram when George Floyd’s death happened, and they said they wanted to listen, so I thought, ‘It’s time for me to speak up about it.’ Now, it’s really worked out for me.”

Her debut album, the upcoming What a Devastating Turn of Events, is a triumph that’s defined by alt-rock guitars, softer confessional moments, and the overriding sense that Chinouriri could be a voice to define indie music for the next decade.

And then there’s the small matter of friends in high places. At a recent Las Vegas residency show, Adele told her fans: “There’s a new artist, she’s British, her name is Rachel [Chinouriri] and she does, like, indie music. She’s absolutely amazing.” Then Adele added that she is planning to attend Chinouriri’s Los Angeles show this spring. “I’m going to go on my own,” she said. “That’s what I’m gonna do.”

Chinouriri has also forged a firm friendship with A-lister Florence Pugh, who recently starred in the music video for ‘Never Need Me’.

It’s for these reasons we’re convinced she might just be the future of music, even if Chinouriri’s arrival has been, in her own words, a “long time coming”. “I’ve been doing music properly since I was 18, so the fact that I’m having my debut album all these years later is kind of mad, but I’ve been on such a massive personal and career journey,” she says.

“I’ve been trying to navigate the industry, and I feel like I’ve hit a point of knowing how to navigate it in the healthiest way possible because it can get really quite bad. But I’ve managed to navigate what I want for my career beyond a TikTok trend too.”

Even if TikTok may have helped Chinouriri’s sound find an early audience through viral hits like the heartbreaking ‘So My Darling’, she admits that the overriding sound of the album is shaped by an era that long predates that site arriving on the scene. “There’s a real noughties flavour to the album, and it’s been interesting because that allows it to become nostalgic,” she says.

“It’s about the idea of missing home, and that for me comes from the nostalgia of turning on the radio and hearing artists like Arctic Monkeys for the first time. It’s not necessarily indie, but I remember hearing MIA’s ‘Paper Planes’ too, and it’s the first time I can recall my brain absorbing music. That’s a thing I miss in a way.”

Home, for Chinouriri, is Croydon, south London, where the singer was raised by Zimbabwean parents. Her strict religious upbringing, she admits, resulted in a situation where it wasn’t always that easy to listen to the music that has now shaped her career.

“My parents wouldn’t let me play non-Christian music, and when they’d leave, my siblings would put on Channel U and MTV and play Eminem, Destiny’s Child. I loved that stuff, but I’ve got three older sisters and one older brother, so they’d just say, ‘Shut up, Rachel!’ And I’d go and do my own thing.”

But one artist that her parents did approve of, however, was Shingai Shoniwa of the Noisettes. “They’d look at her and go: ‘Yes! A Zimbabwean girl doing well, we can let this one slide!’”

She also points to the “unapologetic” and “tough” spirit of Skunk Anansie singer Skin in helping her to navigate the choppy waters of the music industry. “Seeing how unapologetic she was in herself, knowing her art and not wanting to take shit from anyone, that was just fantastic.”

Throughout our chat, you can’t help but sense that Chinouriri has developed the thick skin and pure artistry of those musicians. This has been largely honed, no doubt, from dealing with the aforementioned problems with record labels and casual listeners refusing to accept the artist that Chinouriri actually is.

“From the start, my manager, who is a white man, told me that it would be a struggle to get the message across, and I didn’t think it would be that big of a deal. But within two years, I did feel like I was trying to swim against the stream, and it did get me down.”

She adds, “I’m friends with so many white female artists in the industry, and they already have a tough time. We’ll talk about the same struggles, but I would talk about my added ones, and it became a hard thing to swallow, to realise mine were simply because of my race.”

Still, change is coming, she assures me, and playlist curators at Spotify and Apple have been among those ringing the necessary changes to get Chinouriri where she needs to be. “We’re changing the narrative, but in turn it’s cost me a lot of time and a potentially more successful career because we’re having to fix a bunch of stuff, and I’m glad it’s changing, but it is difficult.”

It has also given her fuel, she explains, to turn up the guitars on her debut album. “I’ve had to consciously make that decision, and of course I love soul, R&B and all the music I grew up with. But even by putting one soulful song in there, the entire campaign could potentially go wrong because everyone focuses on that one thing ’cos it’s easier to market a Black woman in soul or R&B than it ever is with indie.”

There is remarkable candour on the record too. The title track, for instance, is inspired by the story of a cousin who took her own life. Chinouriri says she too has come close to a suicide attempt.

“She took her own life after going through a really tough situation where she basically loved really hard and faced an awful end to a relationship. I hadn’t met her, but I’d heard so much about her, and I learned it was almost a complete copy and paste of what I’d gone through with one of my previous partners,” she reflects, before pausing.

“Thank God, I didn’t take that route. But I’d written suicide letters, I’d gone to the shop to try and buy a rope, and I don’t know what it was that day, but my best friend texted me after not speaking to her for about two weeks. She just said, ‘I’m thinking about you,’ and I just broke down in B&Q. I got an Uber to her house and just broke down.”

Now, Chinouriri says she’s in a much better place altogether. “I’ve been given loads of advice, and the team that helped me was incredible. But that song was the first time I’d ever revealed to my family that I had done that.”

She adds, “It’s not directly my story, that song, but it’s a story which I know I have gone through, and many women have walked it too.”

It’s these life experiences that have informed the shape of the record, Chinouriri explains. It makes a buoyant start through songs such as ‘The Hills’ — drenched in euphoric alt-rock guitars rooted in the late 90s — before a sombre flip takes hold around the midway point. It means that the title track hits with an added punch when it arrives eight songs into the album.

“It’s a weird thing,” she explains. “Life can be just going along and then something flips and everything changes, whether that’s life, death, trauma, or even finding out you’re pregnant. Your life can completely flip unexpectedly. I wanted to flip it and show that somehow we’re all cruising along with these things.”

It’s no wonder that the universally relatable message of heartbreak and hardship is already finding a captive audience at sell-out shows too. Weeks before this interview is published, Chinouriri plays a sell-out show at London’s KOKO before US dates — including that potential meeting with Adele — beckon.

“My team told me: ‘You’ve done four sold-out, 250-capacity venues. You can’t keep doing small venues,’ and I said, ‘Yes! Yes, I can!’ But they suggested KOKO, and when it did sell out, I was actually incredibly shocked. I’m excited to show what I can do as a performer though.”

But if the sadness has got her this far, don’t expect more of the same on album two. Chinouriri is in a place that doesn’t necessarily lend itself to the same circumstances.

“When I was younger, I was so, like, traumatised and surrounded by chaos,” she explains. “So, I always had a complete story to write about. But now I’m in a really healthy place. I’m in a really loving relationship, and I’ve been surrounded by so much love. When my team first met me, I was quite broken, but I hid it quite well. And it was only when they started working with me, they probably noticed. Now, I can’t write a song unless something terrible happens. But I’m surrounded by so much love, I can actually probably write about positive things, which feels like a new challenge to me.”

She adds, “Speaking about the love that surrounds me is seeming like an exciting and a much healthier place to be.”

Taken from the April/May issue of Rolling Stone UK – you can buy it here now.