Marshall’s Ministry of Loud

Ever since masterminding the music industry’s amp of choice 60 years ago, Marshall Amplification has enjoyed a lasting appeal to rival Paul McCartney. Having recently branched out into drums, set up its own thriving record label, and produced a rather covetable range of Marshall-branded fridges, this stalwart is no one-hit wonder

At first glance, Milton Keynes is an unlikely contender for rock’n’roll capital of the world. The Buckinghamshire city is more famous for concrete cows than making musical history. And yet, deep in the suburb of Bletchley, where Alan Turing and his colleagues once deciphered the Nazis’ Enigma machine, another team of British experts have long since cracked the DNA code of loud.

Marshall Amplification has been here since 1966, when it was relocated by founder Jim Marshall, who started the business at his music shop in Hanwell, Ealing, in 1962, alongside son Terry Marshall. They opened a second shop in 1963, and the first Marshall factory in Hayes in 1964, before the move to Milton Keynes. A drummer by trade, Jim’s move into amplification was encouraged by the likes of Pete Townshend and Ritchie Blackmore, later of The Who and Deep Purple respectively, who came to the shop looking for an amp that could handle their distinctively heavy styles.

The first amp Marshall ever made still sits proudly in a glass case in the treasure trove that is the Marshall museum, located at the entrance to the Milton Keynes factory. A vast empire has sprung from that collection of valves and knobs, known as ‘Amp Number One’, aka Marshall’s very first JTM45. The famous, stage-dominating Marshall stack — two 4×12” speaker cabinets on top of each other — followed in 1965, again at Townshend’s behest, and the brand, still 100 per cent independent, now incorporates everything from headphones to a drum company (Natal), a record label, a live booking agency — and even Marshall-branded fridges and craft beer.

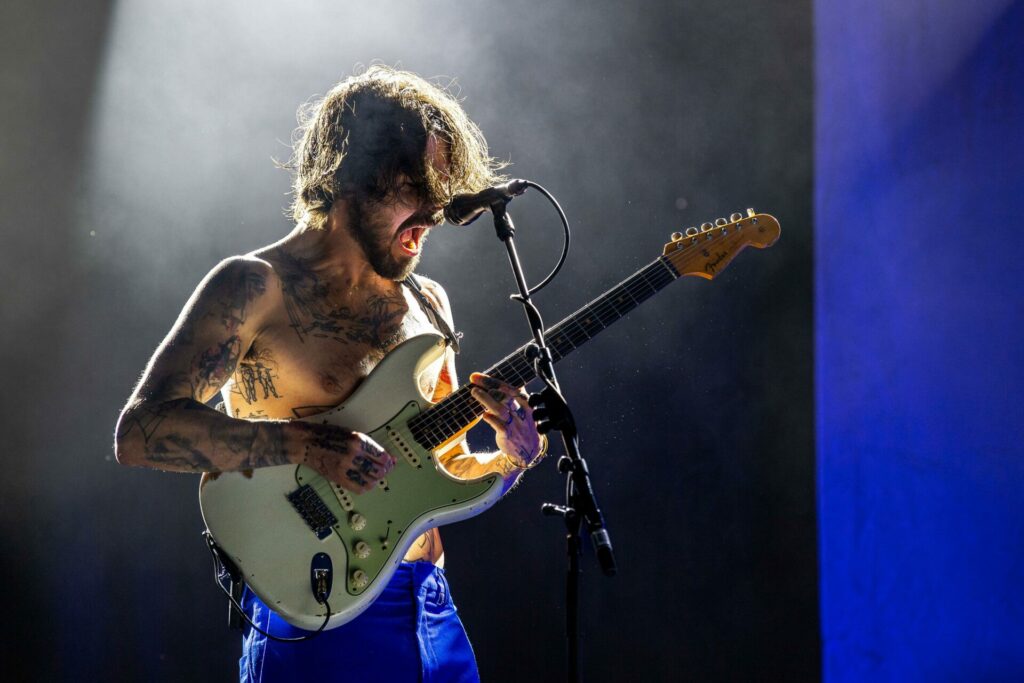

“It’s going to be cockroaches and Marshall amps at the end of the world”

— Simon Neil, Biffy Clyro

Yet the distinctive amps — almost always with a black case, gold controls and white logo — remain at the heart of the enterprise. And, although the technology is ever evolving, the manufacturing process is not so different from Jim Marshall’s day (‘The Father of Loud’ passed away in 2012, aged 88). Walk the shop floor and, alongside the machinery’s heavy metal thunder, it’s notable how many people, rather than machines, are involved. Many amps are still hand-tooled by 200-plus employees, who make around 400 products each week. There’s now another Marshall owned-and-operated factory in Vietnam, but unlike many other brands, that too follows the exact same, painstaking process as its UK counterpart.

“It’s that personal touch that makes every single bit of kit Marshall makes unique,” enthuses Simon Neil, lead singer and guitarist with Scottish rock behemoths Biffy Clyro. “When we go to America and need a Marshall, we know that head [muso speak for ‘amplifier’] has come from the factory and that’s really important.”

Behind every great musician is a great amp — and in most cases it’s a Marshall. In 1966, the brand went global when Jimi Marshall Hendrix first played through a stack, after a venue refused to let him use his own amp. He then demanded an introduction to the man who shared his (middle) name. Other famous fans include Slash from Guns N’ Roses, Oasis, Bring Me the Horizon, Beabadoobee and Kendrick Lamar.

“Slash, Kurt Cobain… My heroes always had a Marshall stack behind them,” recalls Neil. “From being 12 years old looking at those pictures, I wanted to dress like that, have a guitar like that and an amplifier like that. And, even though the world changes and I could never be Slash, it’s still something to aspire to…”

As soon as Neil made any money from playing music, he bought a Marshall head and cab. “There was something about the romance of plugging into that that made me feel like a real musician,” he laughs. “I no longer felt like a pretender; I belonged on stage. Like, I’ve got the gear, now it’s up to me to not fuck it up!”

Biffy Clyro’s rise means that Neil — like his heroes — is also a Marshall devotee. But these days the brand appeals far beyond its traditional cohort of hard rock and heavy metal legends.

Its consumer electronics business (launched in 2010) has opened it up to new demographics; its education division (headed by former Gallows guitarist Steph Carter) reaches out to the next generation of musicians; and its booking agency (which opened last year) and record label (five years earlier) represent distinctly diverse rosters.

Veteran executive Steve Tannett, the brand’s music director, who cut his teeth on Miles Copeland’s IRS Records in the 70s and 80s, was brought in to set up Marshall Records, which is now managed by Peter Capstick. He says the label was always going to break the rock mould.

“It’s not just going to be guys with Marshall stacks and Les Paul guitars,” says Tannett. “We might have some of that, but we’re also going to have really interesting artists, because people who plug guitars into amplifiers don’t all make music like that.

“Artists coming to us don’t have to be preoccupied by thinking the record label’s going to make all the money”

— Steve Tannett, music director of Marshall

“That’s why we’re so pleased at the variety of artists, from the endorser side to the people recording in our studio to the artists we’re releasing on our label. We’re not just one genre. All right, we’re not making dance records, but if you plug your guitar into a Marshall amp and we like your sound, then that’s what we’re about.”

Rising stars Nova Twins are one of those bands. Singer-guitarist Amy Love and bassist Georgia South are about as far away from rock cliché as you can get: two young Black women playing a riotous fusion of punk and grime. They signed to Marshall Records last year and in June delivered the label’s first Top 30 album with Supernova, recorded in the brand’s state-of-the-art studio, which can double as a 250-capacity venue and even has its own bar. (“There are plenty of studios that aren’t in a car park in Milton Keynes,” quips studio manager Adam Beer as he shows us around, “so we had to make this a very special place.”) Love even blagged one of those sought-after Marshall fridges (which look just like the amps) to give someone as a gift.

“When you think of Marshall you think of heritage acts and those black amps,” says Love. “But what’s really cool with our venture with them is they’re changing their perspective. Our deal together is a new way of doing things for both of us. It’s really forward-thinking.”

“Whether it’s a speaker, a fridge or a mug, the Marshall brand is so strong,” adds South. “So it’s cool that they’re expanding with new bands — grassroots bands and women musicians.”

The Nova Twins deal, as with all Marshall contracts, features a 75/25 royalty split in the artist’s favour (much more generous than the traditional major record company deal).

“We’re a business, but it’s all about artists first,” says Tannett. “Artists coming to us don’t have to be preoccupied by thinking the record label’s going to make all the money. Our main objective is to get them as profitable as they can be, as quickly as possible.”

Tannett believes Nova Twins could be Marshall Records’ first stadium-sized superstars. Also signed to the label are maverick artists such as rock-influenced rapper Kid Bookie (who turned up at Marshall Records’ Soho office demanding a deal — “I said, ‘I guess we’d better sign him then,’” laughs Tannett) and punk teens Noah and the Loners, alongside classic rockers Bad Touch and renowned alt-rockers Therapy?.

The rise of Marshall Records has happily coincided with the emergence of a new wave of rock fans.

“We played Slam Dunk and it was the most diverse festival we’ve ever seen, in the crowds and on the stages,” says South.

“There’s a reason rock, metal and alternative music are reviving,” adds Love, “it’s because new people are being allowed in.”

Tannett, meanwhile, believes rock is “more important now than for the last 20 years” and Neil agrees.

“It’s not just greasy blokes with low-cut T-shirts any more,” says the Biffy Clyro frontman. “I don’t mind a bit of that, but the reason guitar and amplifier sales have been going through the roof is because young people who’d maybe have been too intimidated before can now make their music, loud and proud.

“Marshall knows what it’s doing,” he adds. “We don’t need any more 50-year-old white guys playing rock’n’roll — and I say that as an almost 50-year-old white guy playing rock. I want to feel that change. But I love that the guitar has become a way to express yourself again.”

“Our deal together is a new way of doing things for both of us”

— Amy Love, Nova Twins

And whenever musicians hit the road, Marshall will be right there with them.

“You never have a problem with Marshall gear,” says Neil. “It can gig properly. Marshall has the stamina and — I realise I’m about to describe an inanimate object as having the mental acuity to survive a fucking tour — but it does. It feels bulletproof; there’s something military about it that means it will survive you. It’s going to be cockroaches and Marshall amps at the end of the world.”

Tannett, meanwhile, isn’t planning quite that far ahead, happily celebrating one Diamond Jubilee while working towards another very loud 60 years. “We’re a successful business,” he says. “People like our products and we’ve expanded. But there isn’t a moment when we aren’t thinking that we must maintain the same quality and ethos that have allowed us to last 60 years. With a bit of luck, in 60 years, Rolling Stone UK will be writing about 120 years of Marshall. Because Marshall looks forward; it doesn’t look back.”

Taken from the August/September 2022 issue of Rolling Stone UK. Buy it online here.