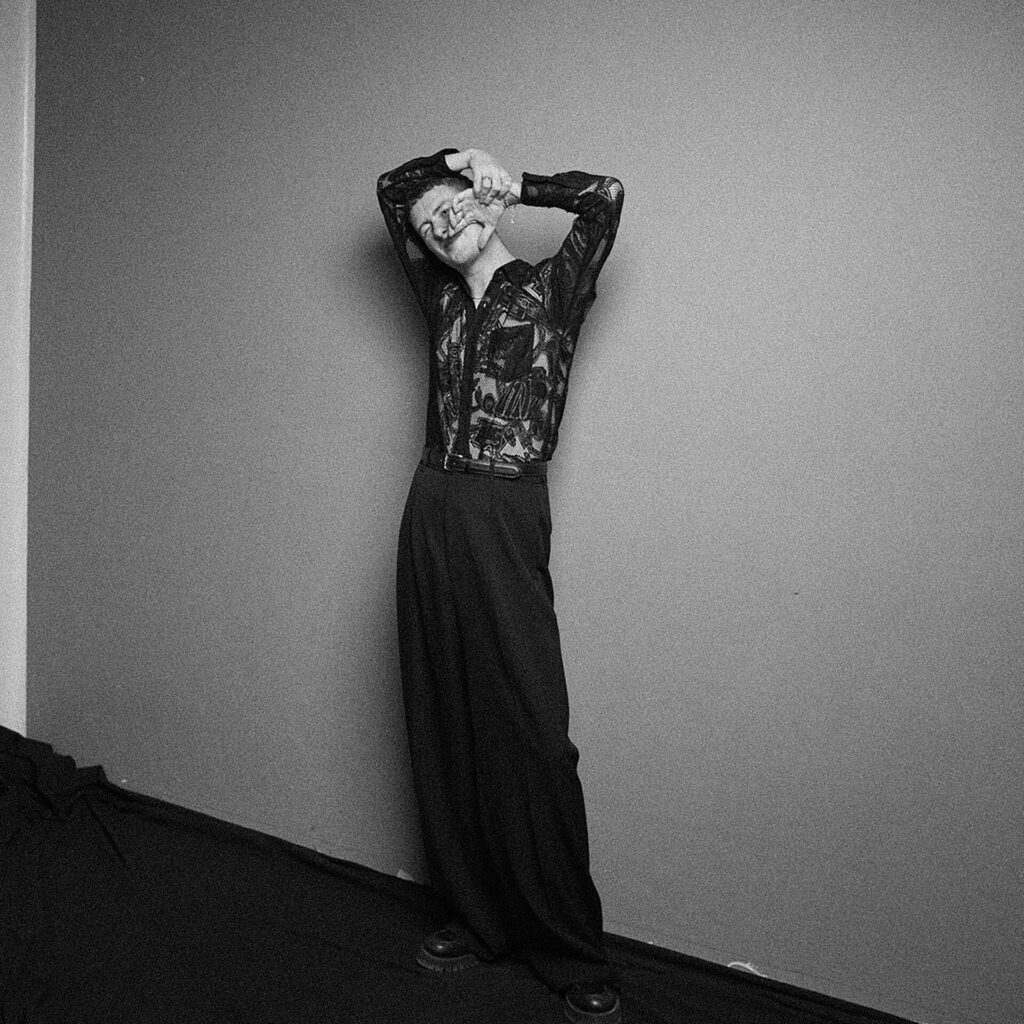

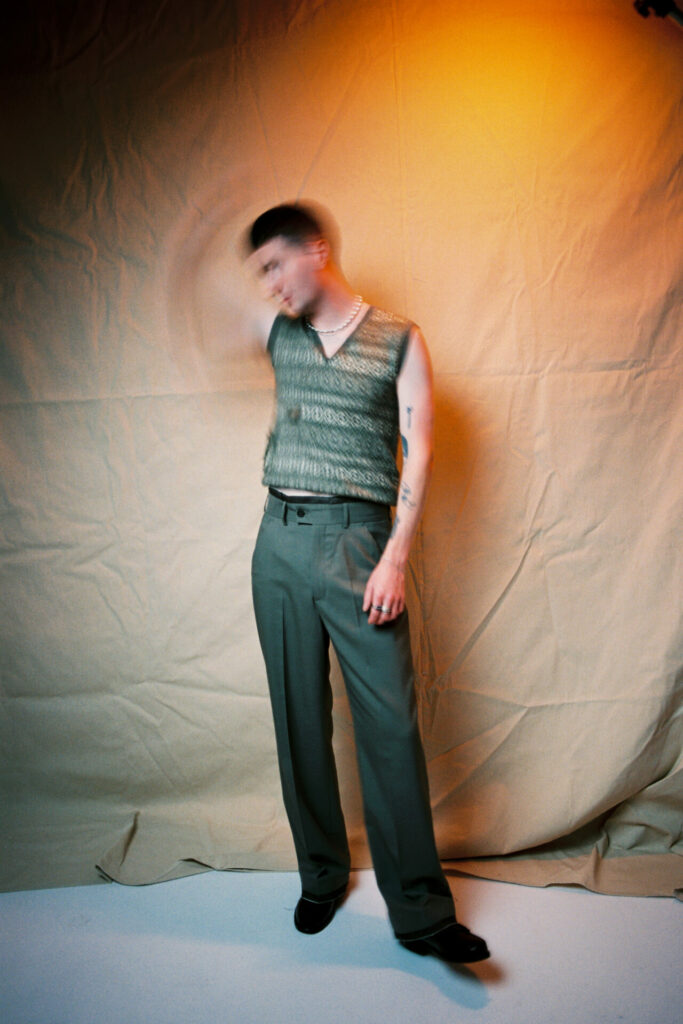

Joesef: a soul stripped bare

Heartfelt lyrics, honey-soaked vocals and luxurious, spine-tingling alt-pop are the order of the day for Joesef. Here, the stand-out Glaswegian singer-songwriter talks hurting, healing and his instinctive ability to smell bullshit from three towns over

By Lee Dalloway

It’s fair to say it’s been a mind-blowing few years for one supremely talented musician from the east end of Glasgow. From bartending 40 hours a week to having the likes of Elton John gush over his vocals, Joesef’s blend of modern soul and unflinchingly honest lyrics have not only garnered acclaim but transformed his life.

“Where I was growing up, it wasn’t really in the stars for me,” says Joesef humbly. “This world is so far removed from my reality. I grew up in quite a deprived area, and everyone in the music industry knows somebody or can afford to get in somehow. I went to music college for a year, but nothing really happened until I went to an open-mic night to support my mate and about nine pints deep, I thought, ‘Fuck it, I’m going to sing.’ The guy who I was with eventually said he wanted to be my manager. He saw something in me that I didn’t see myself, that I must have had a bit of talent.”

This acknowledgement led to Joesef taking music a little more seriously. Connecting his guitar to a laptop, he recorded some demos and posted them on social media and dropped flyers around town ahead of his first real gig. He soon caught the attention of the BBC’s Ones to Watch as he released two EPs of acoustic, lo-fi loveliness: Play Me Something Nice(2019) and Does It Make You Feel Good? (2020). As the world of live music and performance reopened after the pandemic, and with plaudits for his work flooding in, Joesef finally began to believe in himself as a real artist.

“I feel in Glasgow, and alot of northern places, we’re self-deprecating to the point it’s terminal. I struggled a lot with imposter syndrome,” he confides. “That someone is going to tap me on the shoulder, tell me ‘You’re not supposed to be doing this.’ But it was playing live that helped me get my head out of this a little. I kept thinking about the physicality of music; it informed the pace of it.”

Performing live gave him the confidence boost he needed as an artist, but as a human, too. Joesef is quite open about his previous struggles with depression, both in interviews and through his lyrics. “I was so fucking depressed, man! I needed it to lift me,” he recalls. “I always found it quite wanky when people said it was cathartic, but it genuinely is. You’re making a body of work —you don’t get to see the impact it can have on people. My mum was always playing Motown, and that sentiment of bands like The Supremes; heartbreak but delivered to you in a really uplifting way.”

He adds: “It’s quite cathartic playing that live and singing these songs where you felt so alone and so fucked up about stuff, and you see people kissing the person they’re with and swinging their T-shirts above their heads. It’s quite a unifying experience. We’re all in it together; whatever you’re going through, you can leave it out there for an hour and a half.”

His new album Permanent Damage contains his most personally revealing work yet. The title came when looking at the back of a fag packet after the end of a gruelling “balls to the wall” six months of recording. It focuses, in large part, on the break-up of one significant relationship in his life.

“The title speaks to the theme of the record, which, for me, is the permanence of heartbreak —it changed the way I move through the world, how I interact with my mates, how I interact in new relationships. But permanent damage doesn’t necessarily mean to me a negative thing. It’s another term for change,” Joesef asserts, in his belief that sadness can be not only instructive, but also life-affirming and a tool for growth.

“Teaching you about what you do or don’t deserve. It gave me some clarity in things, especially about myself. It shines a light back at myself and looks at my responsibility in everything that went down. I don’t get therapy, so this is my only outlet,” he says.

Joesef also admits to previously doing his most creative work while hungover. “You feel like you’re the last man on earth when you’re rough as fuck,” he explains. “It opens up a little compartment in my brain, where I’m most sad but also most creative. I’m not so much off my rocker these days, but if my life’s going good, sometimes I feel, ‘How can I fuck this up?’”

Although the album is largely about one relationship, standout track ‘Borderline’ is about a second union that was instrumental in his healing. “‘Borderline’ is about the relationship that helped me get over the relationship I was in,” he says. “In this new one, they were so unconditionally loving, I didn’t know how to handle that. I fucked this amazing relationship ’cos of how I’d been treated, and treated people beforehand, and Permanent Damage was the realisation.”

Regarding the subject behind the album’s inspiration, Joesef is fully aware of how difficult it must be to conduct a relationship with a creative individual who writes about their experiences. “They know it’s about them; they’re a good sport,” he laughs. “I could never be in a relationship with a musician! Someone who writes an autobiography about their life and you’re in it, and you don’t know what they’re going to say? Fucking mental,” he says, shaking his head.

Although many people can relate to a relationship so profoundly affecting that it is simultaneously the best and worst thing to ever happen to you, Joesef manages to translate that through his art, both metaphorically in the track ‘Fire’ and visually in the video for ‘Joe’. “In hindsight, what our relationship consisted of was being off our face,” he admits.

“It was fucking mad, but I loved it. It obviously didn’t end well, but it was class while it lasted.” The resolve in the bridge is: “There isn’t a fire hot enough to burn you out of my mind.” It’s about the cyclical nature of heartbreak: no matter how much you try to escape it, it’s always there. “That song was a bit of a breakthrough for me in terms of sonics,” he adds. “It’s cinematic, a James Bond-theme vibe.”As important as the music is how it is portrayed in videos. “The visuals are really important to me,” Joesef explains.

“When I play the music, I can see the films. I want to take that visual language so people can understand the music the way I see it. Music is a visceral experience,” he says. “It’s usually just me and the director Luis Hindman. We love the same films, Sofia Coppola vibes. And we’re real geeks about lighting and talk for ages about colour palettes like boring bastards,” he laughs. “Making music videos is so cool. I’m on set and never thought I’d get to do shit like this. I’m very proud of them. Plus, I get to kiss a handsome boy all day: it’s the best job in the world.”

The stunning video for ‘Joe’ brings to life the romance he’s discussing on much of Permanent Damage. A tumultuous, all-consuming relationship full of passion, heartache, good times and bad that results in the singer-songwriter literally burning down the entire house that saw their relationship bloom, grow and ultimately wither, for a multitude of reasons. His casual, yet dramatic, depiction of the love affair between him and another man is something that’s still all too rare in today’s pop world and was unthinkable even a decade ago.

But the interest in that part of his life still confuses Joesef. “When I first started, all anyone wanted to talk about was my sexuality,” he recalls. “At the point when my music came out, Iwas comfortable enough in myself to be honest in my experiences. I feel very lucky to be making music in this time because that wasn’t always the case. There’s a lot of artists who are openly gay, trans, bi, whatever, now, but in the past, a video like that wouldn’t have got past the boardroom. Certain tabloids did articles on gay issues, totally demonising them.You forget that it was horrendous, people had to go through a lot more than we do now. I feel very lucky.”

In a recent Rolling Stone UK online article , Joesef was in conversation with author Douglas Stuart. Joesef laments: “Queer people who grew up in impoverished backgrounds with alcoholic mothers. I resonated so much with that as you never hear about those stories in those spaces. I feel like I’ve downplayed the things I went through as a result of growing up queer in Glasgow. Just because it serves me no purpose to rehash it with myself,” he says.

“But it’s so nice to have that outlet after all these years of biting my tongue, walking in a certain way, talking in a certain way, just to avoid getting my head kicked in. As much as I can defend myself and handle myself —and I’ve got two older brothers —it was always better just to blend in a wee bit. And I feel like I would have got into music a bit earlier if it wasn’t for that mentality, of not wanting to upset the rhythm.”

He adds: “Music has been my outlet, in the same way that writing has been for Douglas. You can tell your own story; you can take control of your own narrative. That’s really important. People can’t just call you a poof, call you a bender. You’re more than that. You’re a multi-faceted human being with so much more to offer than your sexuality. That’s always been important to me, which is why I’ve always been a bit uneasy with people just focusing on my sexuality. I am that —but I am also so much more.”

It’s his Glaswegian upbringing that has seen Joesef tackle his career and life with a suitably grounded approach, particularly when it comes to the industry he’s forged a career in. “The music industry is amazing, but it can be fickle and shallow,” he cautions. “Keep your wits about you and know it can be taken away, but enjoy it, ’cos it’s not really serious. There’s more important things going on than the statistics of streaming a song. Where I grew up, you can sense general bullshit a mile away. It feels so far removed to a lot of the spaces I’m in these days. It’s all fun, but it’s not real. It’s all marketing… but you get a lot of free drinks,” he laughs.

Ultimately, Joesef is nowhere near as dark as his lyrics might suggest. In person, he’s upbeat and unassuming. When asked what an alternative-universe Joesef would be doing if he hadn’t got his big break, he’s grateful and philosophical. “I think about that a lot, and it keeps me in check ifI find myself down or complaining,” he muses. “I always think what could have been and what could be taken away from me at any point. I don’t know where I’d be if I didn’t have that outlet and something I genuinely care about. A lot of my mates and family hate their jobs, and it’s a privilege. I don’t know what the fuck I’d be doing. I’d be fucked,” he chuckles.

For now, Joesef is brimming with hope as he prepares to drop his debut album. “If you speak to me now, I’m not a particularly dark person. I feel music is my place to exorcise that part of myself. I’m very happy right now. I’m comfortable with myself and my relationships. I’m mostly, like, ‘When is it going to be taken away?’ The impending doom is never that far away. I’m Scottish, so I’m always expecting something bad to happen,” he laughs. “The good weather never lasts very long in Scotland.”