How The Other Half Live: The reality of heading to France as a DIY punk band

Last February, three-piece punk rock band Other Half packed their instruments into a humble Astra and headed to France on tour. From dodging carnets to coughing up for extortionate road tolls, band member Cal Hudson tells Rolling Stone UK how the experience found the band quite possibly for the first time ever coming back from a tour with a few quid in their pockets.

By Cal Hudson

For the uninitiated, as 99 per cent of you will be, Other Half are a scrappy three-piece punk band from Norwich, and have been for a lot longer than we’d like to admit. Having done our time traversing the UK’s ever-struggling DIY venues, we now regularly play to rooms of 50 slightly puzzled people, as opposed to the 10 when we first started. That’s about five extra people per year incrementally, which I think sounds like pretty solid growth. With our job basically done here in Blighty, my bandmates (Sophie — bass/blood-curdling screams and Alfie — drums/card machine operator) and I set our sights on the continent.

Mainland Europe has historically been far too kind to us smelly, UK-based punks, our band having toured there many times in the past. This was of course before our glorious nation decided to burn all our bridges in the name of sovereignty, with your mate and mine, Brexit (I can’t believe that fat-headed portmanteau wormed its way into actual parlance). Where once we could criss-cross the entire continent, going from country to country playing the best gigs of our lives (and getting paid and treated far better than we ever would back home), we now find ourselves in a tangle of impenetrable bureaucracy just thinking about the idea of playing three shows in France. Freedom of movement was a genuinely beautiful thing, something we were so lucky to have access to, and the fact that the powers-that-be duped half the public into thinking otherwise makes me want to pick my eyes out with little Union Jack flags.

Having pined for the continent for so many years, but without the get-up and go to organise it ourselves, when our French friends in Lysistrata offered us three shows as part of their record release tour, we said yes immediately. They are a brilliant little band, dealing in tightly wound noise and displaying a knack for megalithic hooks, with a really fierce French following. They were also offering us some pretty generous guarantees, something that doesn’t usually hold any sway on us, but with all the extra quids that go into traversing France, it sounded quite nice to be able to come home having not lost any money. We have historically operated at a constant (but consistently small) loss as a band, choosing to sell most of our merch for less than the price of a pint, much to the lament of our label, Big Scary Monsters. The idea of monetising the band in any way makes us all feel queasy, and as long as it mostly pays for itself, we’re happy. Hold onto this nugget of information, as it may become important later on.

As a band of over 10 years, for at least eight of those, none of us could drive. We mostly relied on our mums, which I think always gave us the wholesome air of a teenage open-mic group well into our twenties, or more likely, everyone just thought it was a bit weird. We later came to rely on our best friend Chris, who despite having the same pursuits as a 60-year-old man (i.e. watching camping videos on YouTube/constructing an outside bath in his terrace garden) is not any of our parents. Fast-forward to the streamlined Other Half of today and we are all able to drive, but at this point Chris feels like part of the band, and it feels weird if he’s not there constructing salad wraps on the bonnet of our Citroën Berlingo. Speaking of which, our less than trusty Berlingo is due its MOT the day before we leave for France and this becomes our first bone of contention. It’s a car with a rich history of engine faults, the ‘beep’ of which still haunts the darkest corners of my mind, so its chances of passing aren’t exactly likely.

Another thing that Alfie, our most organised member, flags is that it seems Paris has a blanket ban on diesel cars. I refuse to believe this is true, mainly because of our own government’s lack of green initiatives, but we call an emergency meeting at the pub to find out. This proves easier said than done, with multiple official websites proffering completely different information. Some say yes, some say no. Some say you need a special sticker with a particular number and colour denoting your vehicle’s fuel efficiency, and some say said special sticker is irrelevant and you’ll be fined £500 on the spot just pulling into Paris. Some say this came to fruition years ago, and some say not until 2025. The £500 fine actually works out less than the price of hiring a petrol car, so we decide to risk it in Sophie’s little Astra, on the basis that it looks a bit less beat-up than the Berlingo, and therefore less likely to be stopped.

A few days before we’re due to leave, we receive an email from one of the French promoters asking for some forms we hadn’t yet sent/realised existed. The forms in question are regarding Other Half as a business, as we’d technically be ‘working’ abroad, and proof of all the tax the band had paid up until this point to prove we wouldn’t be stealing all of France’s euros. The only problem here being, as mentioned before, we are not a business. Other Half is a stupid hobby where we travel miles and miles to shout at people and sometimes get paid enough to cover petrol, and if we’re very lucky, an out-of-town Travelodge room for the four of us. We don’t earn enough to pay tax, but apparently without any of this proof, we’re told we’re likely to receive a heavily reduced fee, something that suddenly makes this a very expensive-looking jaunt. We leave this with our booking agent, as forms of any kind make us hyperventilate and really, it’s too late in the day to do much about it anyway. Our Airbnb in Paris also decides it’s a great time to call and say they are cancelling our booking, so Alfie scrambles around trying to find somewhere else to stay.

A day before we leave, a friend informs me that it’s a legal requirement to have a carnet for France; basically, an itemised list of everything we are bringing into the country and what it’s all worth, again to make sure we’re not coming to France just to sell all our shit and make a pretty penny tax-free. He says that any discrepancies, however minute, can result in hours upon hours at the border. By this point, we’re about to head to Dover, and realistically I have no idea of the specifics of any of my equipment or how much it’s worth — most of it is encrusted with dirt and held together with gaffer tape. We decide instead to get to our Dover Travelodge and watch some truly heinous reality TV in which couples engage in swinging in a bid to save their relationships. We all decide it gets a bit much when someone is literally getting sucked off on-screen and turn in for the night.

The next day, we enjoy the guaranteed gut-rot of a Travelodge brekkie and head off to the ferry port. As we enter, we do our very best to not look like a band: Chris up front, two hands on the wheel, with Sophie — aka Soapy — acting as a faux partner, while me and Alfie sit in the back doing our best to cover a bass guitar with our coats. We smile heartily at passport control and drive round towards the ferry when we realise we are being ushered into the security check section. Authority scares me, even if I’ve done nothing wrong, and I’m fairly sure I do a Beano-sized gulp when I realise this might be the seven-hour debacle my friend had warned me about. Soapy is fully prepped, though, overtly doing her makeup in a bid to play to the sexism rooted in what we do. ‘Girls don’t play in bands — must just be a family of oddballs,’ we assume the woman must be thinking as she checks our car, when in fact she is obviously just making sure we’re not smuggling 50 kilos of heroin into France.

We make it onto the ferry, giddy in the knowledge that we’ve almost made it onto foreign soil as an undeclared rock band and with 50 kilos of heroin (jk, lol). The ferry has an otherworldly power to transport you back to feeling like a 12-year-old on a school trip and I make the most of this by buying a sub-£5 pint of duty-free Guinness at 9.30 in the morning. To most, this would be the signifier of a man down on his luck, but in the liminal space of a ferry, I feel on top of the world.

We make port in Calais, truly one of the world’s bleakest places, and make a beeline for the Carrefour supermarket, the same supermarket that once upon a time, British louts would have made the pilgrimage to, just to stock up on dirt-cheap piss. Sadly, this is now a distant memory, and we instead buy some expensive apples and paprika crisps to last us until Paris. The Astra is equipped with a CD player and very little else, and as such, we make the most of the CDs Sophie has purchased from charity shops over the previous month. Most make for very difficult listens, with disc two of The Best Pub Jukebox in the World, Ever… proving a bridge too far, but The Darkness’ debut album Permission to Land strikes a chord with us all. With no irony whatsoever, that album still absolutely wallops.

I fall asleep for a while in the heavy gloom of northern France, and awaken in a sun-drenched Paris, which is awash with attractive people smoking cigarettes in open shirts. We pull up at the venue as a very enthusiastic person waves us in — this is Caterina, who we’ve been talking to over email. She kicks two bins out of a parking space for us to pull into and shows us around La Maroquinerie, a beautiful city-centre venue. Lysistrata are soundchecking, but all come to say a nice, warm bonjour. We are two groups cursed with the same kind of bumbling, gentle politeness that I previously thought was only capable of British bands. Ben from Lysistrata is admittedly originally from Bristol, but I can’t imagine that he single-handedly brought that gawky, ham-fisted style of interaction to the French. Anyway, it all feels suitably human, and we all feel very at home straight away.

During our soundcheck, we are introduced to one of the few drawbacks of a well-funded and protected arts system: the volume limiter. Justine, who does our sound, is so incredibly accommodating and kind, something again we are not used to in the UK, but explains that even just Alfie hitting his cymbals is technically too loud. We get this a lot as a band, with Alfie’s preferred style of drumming being really, really hard and really, really fast, to the point where sometimes he is sick in his lap, but we make do in the hope that when there’s a few hundred people in the room it’ll pad out the sound a bit.

We sit down for a cooked meal with everyone else in the venue’s restaurant, plumping for the little table at the very end like the toddlers we are. We’re all vegetarian or vegan, something I think France isn’t quite as hot on, so while everyone else has some very grown-up looking chicken pasta, we have the same pasta presented with a beautiful ring of vegetarian chicken nuggets, adding again to our toddler aesthetic. It is, of course, really tasty, and we’re all enamoured with the little basket of bread we get with our meal. In the UK, you’re lucky if you get a bag of crisps and some fizzy hummus, so we all feel like Queen/the queen as we make our way to the stage, well-fed and watered.

I have a tendency to leave everything to the last minute, and have only just changed the strings on my guitar 15 minutes before we’re due to play. Guitars are an archaic tool that still require the genuinely chilling task of ‘stretching’ the strings to make sure they stay in tune. This means pulling the little metal wires taut, again and again and again, to the point where they feel like they might snap and blind you. In my hurried state, I pull one just that bit too hard and snap it, luckily without any blinding occurring, but by this point my stress poo is at critical mass and I have three minutes to put a new string on and stretch it in once more. I do this while saying fuck a lot and ignoring all the advice and helpful offers from my bandmates.

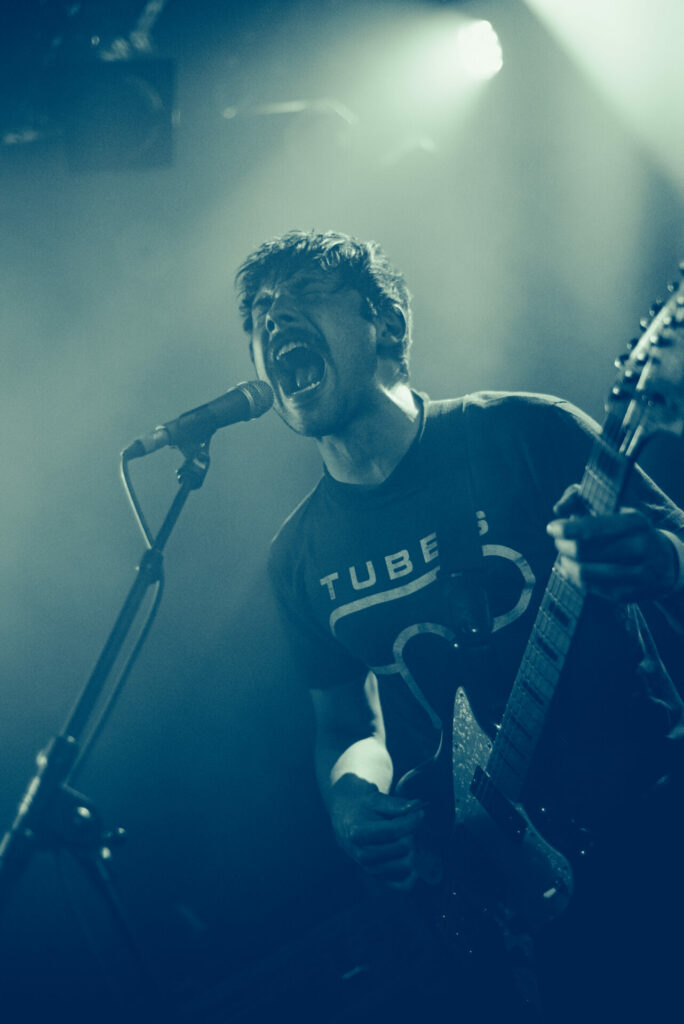

In the end, we rush on stage, greeted by 500 very enthusiastic Parisians. I say a very badly pronounced “Hiya” in French, plug in and play the most out-of-tune chord known to man, then spin directly around to beg Chris to grab my guitar and stretch the strings in some more, while I fumble about getting my spare, much-shitter guitar in tune. All this, in the wrong room with the wrong people, would feel absolutely nightmarish, but luckily every single person crammed into that room is beaming at us, and when I finally play something that sounds vaguely like an Other Half song, they erupt with what feels like a genuinely encouraging cheer, not one of those nasty, mocking ones that British blokes do when a 19-year-old woman drops a tray of drinks in a pub. The gig is lovely, and it’s even more lovely seeing Lysistrata play, the whole crowd holding onto every word. Afterwards, we say our goodbyes and head to our apartment, in a bid to get enough rest to do ignorant tourist stuff the next day.

We awake to a blissfully quiet capital city, just the distant hum of children playing and my newly developed tinnitus. We eat some leftover green-room bread and hummus and set out to see some sights, first trotting around Père Lachaise Cemetery (good for gothy, my-first-band-style promo shots) and then to the Eiffel Tower, which is, admittedly, very big. It’s rare as a band that you get the time to see any of the places where you’re playing, but we always try and thumb in as much as we possibly can. Luckily, because we are playing Paris two nights on the trot, we’re able to mosey around all day without any stress, soaking up the sights and stinks of the nation’s capital.

That night’s show back at La Maroquinerie is just magic. With yesterday’s teething problems out of the way, we play a lot tighter, and the crowd applauds for so long at the end that Alfie cries. Everyone is so receptive and keen to chat afterwards, even though not one of us can string a sentence together in French. It’s all heartening stuff, and I decide to take Lysistrata’s show in from the front for maximum enjoyment. A very eager fan says something along the lines of “Come in, the water is lovely” and pulls me into the mosh, a modest but fervent group of floppy-haired teenagers flailing around and grinning ear-to-ear. This is something I can’t usually abide, because back home it would be some ruddy-faced loser, pouring cider down my back and shouting in my ear to “Come, mosh, you pussy!” but here, I’m gently taken by the hand and proffered an apology afterwards, in case the experience had made me feel uncomfortable. Lovely stuff. At the end of the night, our host Caterina sees us off with bags full of food and drink and a hug. It feels very motherly, like we’re leaving home to go to uni, and we all make a pact to concentrate on our studies and always rubber up.

The next day, we have a six-hour drive to La Rochelle, a coastal city in western France, and come into contact with France’s toll road system. We’re expecting your usual sub 10-euro payout but get stung for 25, then 30, then 25 again, then 50, then 30 again. It’s a hammering that would be easier to stomach knowing we were getting our full fee for tonight, but we had almost wondered if we’d been forgotten about in the lead up to the gig. We were only added onto the poster a week before the show, then received an email saying that we would in fact be playing in a different room from everyone else, with us being advertised as the pre-gig gig. This, plus all the tax form stuff, had us pretty worried that our guarantee might not be anything like the amount we’d originally been promised. This wasn’t helped by the fact that when we pull into La Rochelle, the place is absolutely deserted. Like one of those fake towns made for nuclear testing, there’s a lot of boarded-up shop fronts but no people, and as we slowly drive past rows of empty buildings on a Saturday afternoon, we can’t help but think that 1,500 people turning up out of nowhere for a punk gig seems pretty unlikely.

We arrive at the hotel that the venue has very kindly booked for us, which, too, is absolutely deserted. We use a code to get in and are greeted by a partial building site, with a lift shaft having been recently removed from the building and chipboard half covering the open walls. We’re not a fussy bunch, but this is only adding to our fear that we’ve been led to this fake town as a ritual sacrifice to the pagan Gods of France. We decide the sweet boys in Lysistrata would never do that to us and head to the venue in the hope it is situated in a slightly more inhabited part of town. As we drive into yet more industrialised stretches of tarmac, riddled with diversions and flanked by what we find out are old Nazi U-boat pens, it’s clear it is not.

La Sirène, the venue we’re playing tonight, is a foreboding three-storey structure, perched on the quay. We sheepishly creep up a flight of stairs, and then another, unsure about where on earth we’re meant to be, until we come across a tall, punkish-looking man. This is Mathieu, who we’ve been talking to via email. He takes us down to our green room, which is the real deal. All shiny and new, filled with fluffy white towels, three types of water and a fridge full of beer, plonk and pop. Mathieu asks if the wine he has left for us is OK. We say that it is, although literally any bottle of wine would be. He then takes us through to the ‘small room’ we’d be playing in. The ‘small room’ is, of course, 10 times the size of any venue we would play in the UK, about 500 capacity, so we are once again doubtful that 500 people are suddenly going to appear out of thin air to see us in two hours’ time. We soundcheck, and then Mathieu returns to invite us downstairs for an “oyster reception”. We all look at each other quizzically, but say yes.

We head downstairs to a foyer full of clinking wine glasses and the aforementioned oysters, hundreds of the things, surrounded by a spread of crudités and the most fuck-off prawns I’ve ever seen. It’s all very strange but certainly nicer than some po-faced show rep tutting when you ask if there is any food for the bands. I don’t eat meat, but I do make exceptions if something is free, and having never tried an oyster before, I feel it is my duty to give it a go. The boys in Lysistrata watch in glee as I struggle first to get the ominous gloop out of the shell, then as I struggle even more to get it down. I refuse to believe anyone could possibly enjoy the experience, to which Ben tells me that it’s tradition in France to have 12 in a row on Christmas Day. Awful.

The show later on is really fun, and 1,500 people do indeed materialise out of nowhere to fill both the club room we are playing, and the massive main hall where Lysistrata hold fort. It’s a really wonderful night and testament to what you can achieve when your government actively invests in the arts. Lysistrata tell us that they are essentially sponsored by the French government to fully concentrate on making music, with La Sirène acting as their base, providing free rehearsal space, recording studios and a platform to play to thousands of people. It’s a bleak contrast to our country’s view on the arts, with 125 small venues closing their doors forever in 2023 alone. Fearing I will never be this well treated again, I over-indulge in red wine and prove very hard work on the drive back to the hotel, losing the keys to our room (they are in my back pocket).

A few weeks later, after returning home, we find that we haven’t had our fees cut nearly as dramatically as first thought and although we definitely haven’t made money on the trip, we also haven’t lost any, which for us feels massive. We are of course still in debt as a band, having just recorded our third album, but the endless money pit doesn’t seem quite so deep anymore. It’s interesting how France is fully willing to invest in the arts, and not just “high-brow” stuff confined to theatres, but, as they refer to it, “actual” music. In the UK, I guess the government is happy taking all of Ed Sheeran’s quids in tax without thinking about where he came from or how he got there, but I think it’s important to think, too, about the other end of the scale.

Not only will these future artists all be from a certain economic background, with rising costs and a lack of opportunities pricing out anyone not already “of money”, but so too there is huge cultural importance in music made for 50 people in the back room of a pub. Not everything has to be arena-sized in ambition, but with the lack of help for independent venues and working-class musicians here in the UK, this is the way it will go. I don’t want to play stadium rock at Co-Op Live arena, I want to play shitty punk at a co-op DIY venue, and that’s just fine.