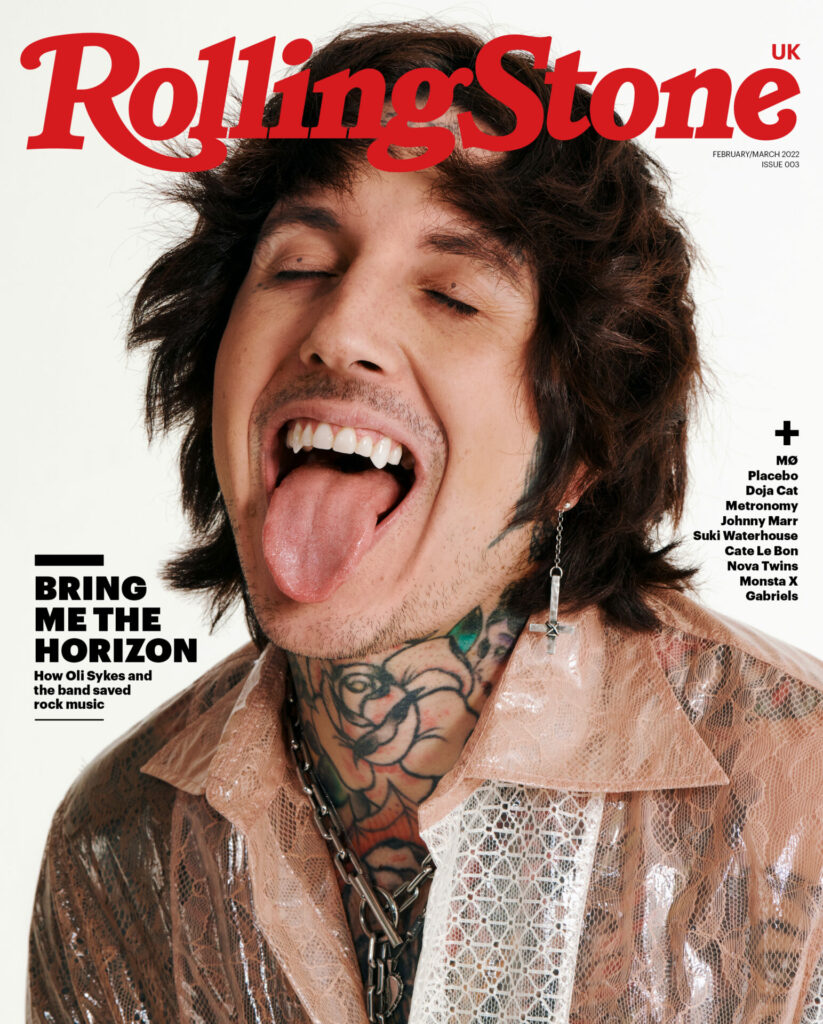

How Bring Me The Horizon saved British rock

As Bring Me The Horizon cover Rolling Stone UK's third issue, they tell the story of how they became the saviours of British rock

By Hannah Ewens

Oli Sykes lived the great coronavirus pandemic narrative arc. He dissociated using Netflix and games, slipped into existential crisis, returned to old vices and tried to ameliorate some of the discomfort and confusion he felt with art. His experience differs from the rest of us in that Bring Me The Horizon’s lockdown project was not just banana bread. It was a series of long Zoom calls that resulted in an EP that brought them, as drummer Mat Nicholls admits, a reinvigorated fanbase and universal critical praise for “the best stuff we’ve done in years”.

Following up a masterpiece requires thought, patience and a change of scenery, and for this the band has chosen Los Angeles. To British sensibilities, it is a strange winter morning: sunny enough to burn, while the heat and smog have made a primordial broth that collects around the infinity pool and rolls off vertically across the open valley. It is a scene befitting a band whose aforementioned pandemic-themed EP was named Post Human: Survival Horror.

Bring Me The Horizon have been staying in this vast hillside property made from polished black rock to experiment on music for the next EP in their Post Human series. It would not be a stretch to call it a mansion of the kind owned by a Marvel villain or malevolent tech bro. The neighbouring house has raging parties every weekend: the band assumes it is a rental property because no one can live like that. At least not Bring Me The Horizon, half of whom avoid drinking and follow a disciplined regimen of morning gym sessions and home for healthy dinners and bed by half nine.

Frontman Oli Sykes strolls onto the veranda for our interview like a vampire in reverse, his body opening to the light. I notice that he does, in fact, have fangs. He and his wife, the model and singer Alissa Salls, got the pointy teeth permanently affixed last summer.

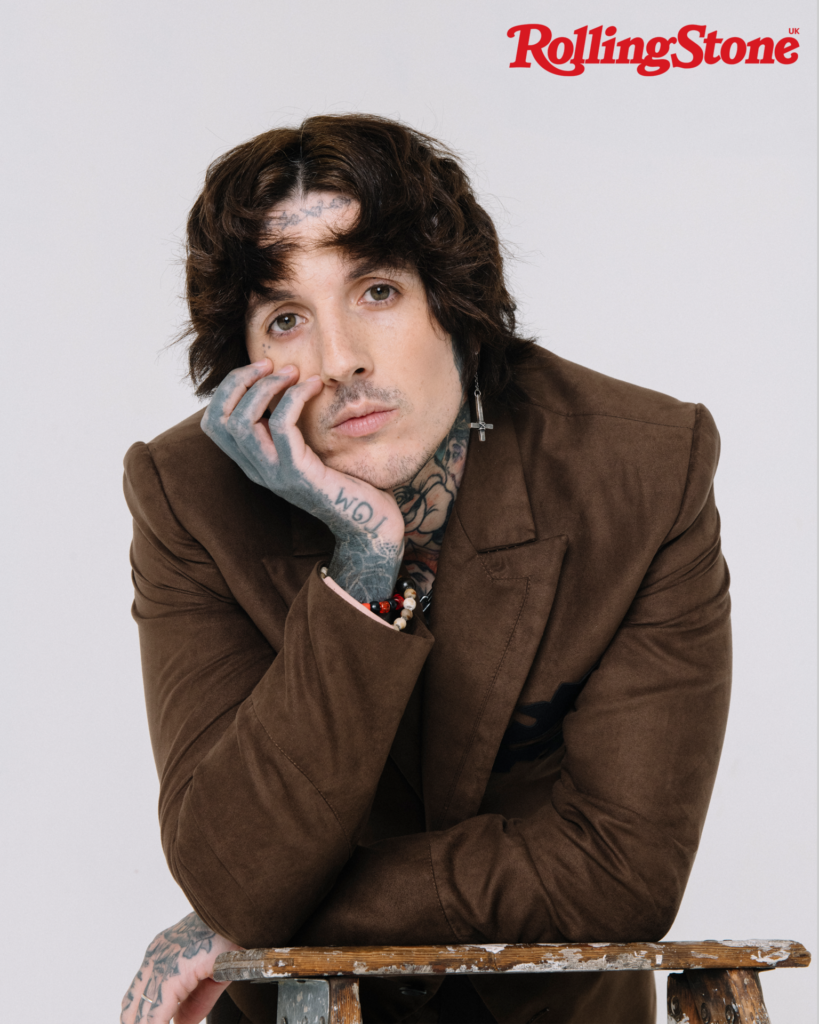

Contrary to his job, confident social media presence and incendiary live performances, he has always been socially shy. That said, when given a routine question in an interview — despite the monochromatic Yorkshire colour to his tone and quiet lack of assertion — he will always give the most depressing or truthful answer. This mysterious contrast takes you by surprise. Here, in a white handwoven shirt, black Prada utility boots with monogrammed wallet, and a crucifix earring, he is evidently comfortable in his temporary home of five weeks. Fans have noticed the change over the past few months, commenting on social media that he looks the healthiest and happiest he ever has.

“I’d been searching for ages to write something that was bigger than myself but I’m not educated politically; I couldn’t write a political album,” Sykes says of Survival Horror, sitting on the boiling grey patio furniture with his back to the sun. He wrote first single ‘Parasite Eve’ before the Covid-19 pandemic, interested in themes of apocalypse and geopolitics. The lyric “if we survive the infection / will we remember the lesson”, made Sykes and the whole band uneasy as 2020 unfolded. Was this grossly offensive when people were in hospitals dying? As the pandemic progressed, they decided to release the track in June with the revised lyric: “when we forget the infection / will we remember the lesson?”

“I’d been searching for ages to write something that was bigger than myself but I’m not educated politically; I couldn’t write a political album”

Only a band with the atheism and gallows humour of Bring Me The Horizon could get away with music as on the nose as this: a rock song about the corruption of pandemic life, that opens with the words “I’ve got a fever, don’t breathe on me” and issues the automated notification (voiced by Sykes’ wife): “Please, remain calm, the end has arrived”, like listeners are on the precipice of a rollercoaster drop rather than four months into waiting for a killer virus to reach them. It could have meant social media cancellation, perceived as a distasteful move impossible to return from. Instead, it was an immediate hit that provided catharsis for isolated rock fans who were fearing for loved ones and, in some no-longer-abstract way, future humanity.

The Guardian retrospectively called Survival Horror “the first great piece of art about the pandemic” and it was, impressively so. Most artists, unable to tour, did not put out music in 2020. Work across all creative mediums went in one of two directions: reacting against it with fantasy or escapism, or grabbing the collective condition by the horns and wrestling it into submission. The band took the risk of doing the latter, along with pop star Charli XCX’s how i’m feeling now and comedian and filmmaker Bo Burnham’s Bo Burnham: Inside.

With these notable pieces of pandemic art, makers documented the effects of being stuck inside, verbalising the shifts in our communal emotional experience that happened week by week, month by month. The opening track on Survival Horror is even called ‘Dear Diary,’ with lyrics that double up as Sykes’ commentary on daily lockdown insanity. (Again, few would try and succeed in pulling off the bleakly hilarious “Ah, never mind, it’s not the end of the world (oh, wait)” before a purgative sonic breakdown.)

“Everyone got depressed to a degree, didn’t they? The pandemic lifted the veil of the way life is,” Sykes says. His mood was matched by others in the band, including Nicholls, who, in lockdown in Sheffield with his furloughed girlfriend, used exercise as a crutch. Following an injury, Nicholls was bereft of something to cling to mentally. Sykes realised that the matrix of life allowed him to divert from what was going on underneath: when the band toured and he was immersed in writing albums, he was happy. Once life stopped, nothing worked because he had no support system or balanced way of living. This was probably the same for anyone who throws themselves into their job, he says.

To him, this personal reality reflected the world at large. “Not to get too nihilistic, but life is so pointless,” he says. Work, commuting, certain relationships, capitalistic routines: we could live without them, he believes. “It’s a feeling that I can’t shake even now: seeing how the meat was made.” Without these distractions he started to realise the degree to which he was an insecure person. “I would never really look at myself. I was very down on myself about everything. So much of my self-worth came from playing gigs and songs going well and when all that went, I questioned my self-worth completely.”

Sykes has spoken publicly about the ketamine addiction that plagued him in the 2010s. It allowed him to sever his mind from those same insecurities. “I could take ketamine and I wasn’t Oli Sykes,” he says now. “I could think about our band but I couldn’t attach it to any meaning. The ego’s just gone. Everything loses every sense and you’re gone.” This was the subject matter for 2013’s Sempiternal, one of the best rock albums of the decade, a more palatable blend of metal and electronica than their earlier work. He had since abstained completely from the drug.

At the start of the pandemic, Sykes drank and smoked weed, but his internal discomfort coincided with his dealer selling harder drugs. “At first I thought: ‘Just do it for a bit of fun to pass time. I ain’t gonna get back into that shit, I’ve got too much to live for.’ That’s what I honestly thought when I started doing it again.” The realisation quickly dawned on him when the drug provided dissociative relief: he was seeking that same escape. It was a struggle, but he managed to work on Survival Horror remotely while using ketamine without anyone realising.

He was temporarily living with his wife and his parents in his house in Sheffield. Salls discovered his drug use and told his parents, who had previously been involved with his addiction and recovery: his father had given him lifts to pick up drugs in order to keep him safe, and previous rehab experiences have had their support and involvement.

Sykes was immensely miserable and disappointed in himself. “I just couldn’t believe that I’d gone back there,” he says, with resignation in his voice. “The last time I got addicted, the girls in my life were in and out, I wasn’t married to someone. Obviously at the time I knew people were upset and scared for me, but with Alissa, I might as well have cheated with her; the way it affects you is the same. If someone’s doing something behind your back and you find out about it, it’s a betrayal. The trust was completely shattered. I was getting by because I was smoking weed, so I think she thought I was maybe smoking a bit too much. She had no idea. She’d never even seen anyone doing hard drugs before. She was terrified, she thought I was gonna die. That was a realisation of: ‘I’ve not just fucked myself up, I’ve fucked up this other person who is completely dedicated to me.’”

Social media became another addiction during the pandemic, albeit a societally condoned one. Using it provided a window into Sykes’ insecurities around who he was, his looks, what he had achieved (or not), whether his band was cool enough. “It doesn’t matter if you’re a 14-year-old girl or a rock star who’s doing well, mindlessly scrolling affects you mentally in the same way: it gives you this grey, existential crisis-type feeling.”

“Alissa had never seen anyone doing hard drugs before. She thought I was gonna die. That was a realisation of: ‘I’ve not just fucked myself up, I’ve fucked up this other person who is completely dedicated to me’”

In July 2021, Sykes started regular therapy for the first time and in October, he and Salls went to her home country, Brazil, which they intend to use as a base. In a Brazilian ashram (spiritual hermitage) for a month, no phones allowed, Sykes could learn who he was outside the structure of the band. He knows it sounds simple but he discovered that he is surprisingly normal and possesses the ability to find happiness in small pleasures: dog-walking, eating delicious food, playing video games, helping other people make their art. He is also a family man. “I didn’t realise how much family meant to me and how good they make me feel. I’d not even pick up a phone when I’m on tour for months to say hello…”

Thanks to therapy and the wisdom of hindsight, this statement resonates with him as he reflects on the way he coped before 2020: “I was more distracted than healed.”

From the start, Bring Me The Horizon’s story was a reactionary one of love and hate, death and rebirth. They formed in Sheffield in 2004. Nicholls, who was from Rotherham (“a complete shithole and even worse now” by his estimation) met Sykes at alternative nights for underage kids in the city centre. Sykes was an unpopular child who repeatedly got beaten up at school. Though highly creative, his ADHD diagnosis at the age of six set him up for unsatisfying experiences in the classroom. Heavy music was an outlet. Nicholls knew guitarists Lee Malia and Curtis Ward who played in a Metallica cover band and suggested to Sykes that they create their own group. “None of us knew what we were doing. We just wanted to make heavy music that people could mosh to,” remembers Malia.

It didn’t take long for the teens of Myspace to decide that this scrappy band were infamous scene kids. At one point, Bring Me The Horizon was the most played artist on the platform, ahead of musicians like Coldplay, Lily Allen and Adele. “It was very much: the scene decides,” says bass player Matt Kean. “It wasn’t about press liking it, or if your dad’s in a band or what budget you’ve got, or any of the other things that contribute to making an artist big.”

Sykes, still a teenager, was a fashion influencer and social media celebrity at a time when those ideas were being manifested on the first digital platform of its kind. Shortly after starting the band, Sykes launched his alternative clothing brand Drop Dead, which is still prosperous today. By its second year, his ability to predict and direct the neon, grotesque, hardcore aesthetic of the platform was turning over hundreds of thousands of pounds. If you were into heavy music, you not only knew who he was, but you had an opinion on him and his band. Whether you loved or hated them, you went to their shows wearing one of his T-shirts.

Male-dominated rock media was hostile to them, a reaction that seemed to come from resenting the democratisation of their success, the generic deathcore of their early music and what they perceived as Sykes’ good looks and poor attitude. “We felt the hatred, especially with the press,” says Kean. “It’s probably because we were so young but everyone in the rock press seemed so old and didn’t like the fact they had to put us in their magazines but had to because they knew we sold.” For a sector of rock fans who reflected the press, the band were not metal enough.

After their third album, There Is a Hell Believe Me I’ve Seen It. (2010), there were internal problems. “I was a massive stoner back then so I was oblivious to everything,” remembers Nicholls. “But it got to a point where [Sykes] was doing our head in. We avoided hanging out with him, which is sad. We didn’t even know if we’d be a band any more.” On a failed writing trip in the Lake District, Sykes told them he needed to go to rehab. A previous attempt had been unsuccessful, but this time it would prove to be worthwhile. “It sorted us all out because we saw it as this cleansing, if you will. We suddenly had a major label deal too and thought, ‘Let’s show everyone what we can do when we fully focus,’” says Nicholls.

“We’re too creative to be a straight-up arena rock band”

The result, with keyboardist-meets-producer Jordan Fish newly onboard, was 2013’s Sempiternal. Across their following albums, each with broader appeal, listeners who had wanted them out of metal were annoyed that they were branching out into other genres. Their fanbase grew with each album, especially the anthemic pop-rock of That’s The Spirit (2015). What happened, again, was another reactionary pivot. The next album, amo, had to be different. “We’re too creative to be a straight-up arena rock band,” reflects Fish. “Oli’s got too much creativity to be in that band. So amo felt like a bit of a reset to break that trajectory.”

Their sixth record, amo, was a product of just under two years’ work, and was released in 2019. It gave them a taste of what they craved: a No. 1 album and Grammy nominations. But ironically, despite these accolades, it was their most divisive record among their fanbase and received lukewarm reviews. The idea of a four-part EP series was born from this experience: immense time and resources for the album format equals bigger stressors.

For Sykes, the negativity around amo stayed at the forefront of his mind. “I’m still so proud of that record, but it’s a mental toll on you when you put so much work into it and it feels like so much is riding on it, that one bad comment about it ruins your life. Your self-worth becomes how many records you sell or if you get a No. 1.” Losing out on Grammys for amo was a disappointment, too. “You’re looking around at all these other artists doing so much better than you and bigger than you: it pollutes your mind,” he says.

The rest of the band are more forthcoming about amo’s limitations. Nicholls admits that it was the first album where the band tried to “tick boxes” to ensure its mainstream success. Messing with the unique Bring Me The Horizon formula backfired. “amo was missing something and people knew it and we realised it,” he says. “We came to America and it didn’t really resonate with anyone. We had a really hard time. We thought, ‘We’re in decline now.’”

“amo was missing something and people knew it and we realised it”

They were wrong, though, as amo proved to be another opportunity to propel Bring Me The Horizon forward and elsewhere. Sam Coare, MD of Alternative Press and previous editor of Kerrang!, believes that Sykes’ need to reinvent himself and the band is what makes them both fascinating to follow and polarising to the dominant heavy music fan who likes artists to fit in neatly defined boxes. “AC/DC have made a career of writing the same song for 45 years, but it doesn’t feel like now you can stay in the same lane for 45 days without being old hat. Sykes more than anyone understands how kids work in a world of decreasing attention spans. You’d back a band that was starting today that had Oli Sykes as the figurehead, more than you would Dave Grohl,” Coare says.

Reliable, respected Grohl is an interesting counterpoint for a regenerative rock artist like Sykes, particularly emerging from a decade when the genre felt uninventive and reliant on legacy acts. When asked about goals for the band, Malia mentions him too: “If you say Foo Fighters, everyone in the world knows that band. We’re not that yet.” By capturing the zeitgeist on their last record, Bring Me The Horizon went some way to forging their own legacy: one of bringing British rock out of its ten-year mainstream stagnation, a singular feat.

Sykes has frequently been vocal about modern rock music being stale but feels differently now. He is inspired by a scene of young alternative artists and has become something of a screamo Travis Barker, collaborating with and promoting many of them to celebrate and integrate himself with youth culture. “So many of this new scene grew up on Bring Me The Horizon, it makes me feel like a proud Dad,” he says. Fish is similarly feeling more settled in the genre, after the triumph of the heavier, guitar-focussed Survival Horror. “We’re more comfortable with being a rock band for a minute,” he says. “We realised we don’t have to be obtuse and awkward.”

“We’re more comfortable with being a rock band for a minute. We realised we don’t have to be obtuse and awkward.”

The band and their company stroll along the Hollywood Walk of Fame. A high-spirited Nicholls wants to know where their terrazzo and brass star is. Given that, on leaving the bar five minutes ago, the six-foot-one, newly hench Sykes was celeb-spotted trailing at the back of the pack (“What the fuck?! That’s fucking Oli Sykes!”), it would make sense for Bring Me The Horizon to have one. Fish pipes up to the manager, continuing the joke: “You said we’d come to America and get a star!” Alongside them, Sykes says, quite innocently, “Can you still get stars?”

They’ve all managed to stay awake past their half-nine curfew for Sykes’ DJ appearance with Papa Roach frontman Jacoby Shaddix for the alternative club night, Emo Nite, at Avalon Hollywood. It’s a British alt night on steroids. Everywhere smells like weed and light beer and the dress code appears to be Avril Lavigne meets Playboy Mansion: angel wings, tartan, body-con dresses and stripper heels.

Onstage, Sykes is initially like the sober person at a 5am afterparty and with good reason: this is intense. He smiles politely and occasionally tosses a deathcore scream down the mic as nonchalantly as if he were delivering a bouncy ball to a small child. Before long, it appears that everyone having the night of their lives allows Sykes to loosen up and he starts to beam. If vast swathes of the room did not video Oli Sykes DJing ‘Buck Rogers’ or automatically entering karaoke mode for the “–bortion, –bortion, –bortion” bit of ‘Fat Lip’, while Shaddix headbanged his wedge of upright hair, few would believe this bizarrely magical scene happened.

Little at Emo Nite was emo-specific but the word is more meaningless than ever. As Kean says, “Everyone’s got a different idea of what emo is and that’s telling of what kind of genre it is.” Hardcore? Emo. Acoustic guitars? Emo. Sad pop music? Emo. Its usage to mean almost anything emotional was accelerated by Gen Z learning about the genre through the nostalgic and flattening lens of TikTok.

During the pandemic, Sempiternal’s ‘Can You Feel My Heart’ went viral on the platform. The song is currently their biggest hit, up by 200 million streams on Spotify in a year. This overnight reach to a new, younger fanbase forced Sykes onto the app to promote his band.

To these teens, Oli Sykes is practically a Godfather of emo. “‘Can You Feel My Heart’ is ten years old now and came at the end of that [Myspace-emo] scene,” he says. “Extreme emotion disappeared for ten years and kids are rediscovering that level of it. That’s why I think we’ve got a chance, because we’re highly emotive — that’s our bread and butter.”

The forthcoming second EP will aim to create a “future emo” sound: reimagining the genre as something that feels fresh in 2022. While here, they’ve listened to their teenage favourites that fall into the emo/screamo category for inspiration: Taking Back Sunday, My Chemical Romance, The Used, Glassjaw. The latter is especially resonant for Fish, whose previous band was named after their second album, Worship and Tribute.

‘DiE4u’, the first single from the EP, released in 2021, was their earliest working attempt at capturing “future emo” after months of initial experimentation. The pop-rock track features melodramatic and bodily imagery to pin it lyrically in pure emo territory (“‘Cause the truth of it, you could slit my wrists / And I’d write your name in a heart with the haemorrhage”) and an irritatingly moreish chorus with a pendulum swing that suits the subject matter: addiction.

Bring Me The Horizon albums are themed around events in Sykes’ life — addiction, rehab, love, divorce — as is this next EP. The theme is recovery, and his hope is that, through exploring his own recovery from addiction, he can touch on the recovery of society post-pandemic and of the world suffering from climate change. To his mind, someone who hates who they are is unlikely to consider others or help to save the planet.

“With this record, I’m going to try to teach people to have compassion for themselves, as someone who fucking hated themselves,” the frontman explains. “It used to make me sick to hear ‘you’ve got to love yourself’ — never. I used to put all my awards in a cupboard, I wouldn’t look at them. If someone asked me what I did, I would never say I was in a band, I’d say I own a clothing company or a restaurant. I just didn’t wanna talk about it. Now I love myself. I can look in the mirror and go ‘You’re doing good.’ I can say ‘I’m a rock star, my band’s doing well.’”

“It used to make me sick to hear ‘you’ve got to love yourself’ – never. I used to put all my awards in a cupboard, I wouldn’t look at them.”

It is why he is now protective of his self-care; nothing comes between Sykes and his gym routine. His Instagram is inactive until midday and he only checks it if he must. There will be no unnecessary hard work. Boundaries are in full enforcement around this writing trip. The other day, Nadia Tolokonnikova from Pussy Riot asked him how many songs he aimed to complete on the trip and was shocked when he said “one”. And they do have one song that feels promising: it involves the lyric “we’re just a roomful of strangers looking for something to save us”. Imagine how amazing that would be for fans to hear live in a room of people they’ve never met, he says. Instead of finishing that song, they will use their final day in the studio to generate more ideas. “I’m just trying to remove all that pressure that makes it suck to be in a band,” he shrugs.

The other EPs in the series will play in various genres. The third is electronic, something Fish is eagerly awaiting since that is his wheelhouse. They are quiet about the fourth to not get people’s hopes up, bar Malia, who suggests it will be “heavy”. This chimes with Sykes’ intriguing moral for the series — that history can easily repeat itself.

During Sykes’ shoot for Rolling Stone UK, Fish sits on the floor against the studio wall quietly waiting for his food to arrive. He seems a little downtrodden, possibly tired. In actuality, he claims he is finally pleased with the trip because they are no longer at the start of the EP 2 creation process. “The beginning is the biggest head fuck. It’s a big, blank slate, which is just horrible,” he says, bluntly. There is no definite second single yet but there’s a platter of ideas to develop in early 2022, after their Christmas break with their families.

While Sykes feels free in their current creative stage, Fish is visibly shouldering the burden of finishing this project. He is a self-professed hard-worker who likes structure and results. “My whole life and whole mood is very dependent on where we are with songs and writing,” he admits. Work has been a faithful method to self-soothe his anxiety since childhood but possibly one that perpetuates the problem.

Since Fish joined the band, the undeniable chemistry between him and Sykes became Bring Me The Horizon’s magic formula. It is a dynamic that has remained steadfast: If Sykes is the mad genius, Fish is the technical virtuoso. Neither would quite work without the other. (“They’re Oli and Jordan’s songs,” Nicholls says happily).

“Oli’s always been the creative director with the vision,” explains Fish. “I’m just trying to help fulfil his vision, to be honest with you. Often it’s me making stuff up and seeing if I can get a bite from him.” Hence Fish spent the whole trip at the studio early while the others were at the gym: to set out his pieces of bait to catch Sykes and his imagination. It is an emotionally volatile, hit-and-miss approach for Fish. “If something I’ve made goes down well and we end up creating a song out of it, it’s an amazing feeling. On the other hand, if we don’t have anything, it’s awful.”

Has his propensity to guess Sykes’ reaction become more finely tuned as the years progress? “No,” Fish laughs. “I still don’t really know. The only thing I do know is that he doesn’t like it if I make something that seems normal.”

Fish has accepted — you sense at least in part reluctantly — that this EP will take as long as it needs to. The series was supposed to be completed swiftly, but realistically the inventiveness and high production values that Bring Me The Horizon demand of themselves would never be compromised. “I think we have very high standards for a rock band,” Fish says plainly. “Most bands put out songs with so many skippers: ‘That’ll do.’ Every time, I want to be able to think, ‘Our record is the best album to come out in rock music this year.’”

Regardless, it will be completed before the summer. In a milestone moment for the band, they will headline Reading & Leeds Festival in August 2022, alongside leading artists like Arctic Monkeys and Dave. The festival’s booker Jon McIldowie says, “Bring Me were always going to be a Reading & Leeds-headlining band, it was just a matter of when.” McIldowie watched the London O2 show on their 2021 arena tour and knew he had to book them to headline. “It was one of those shows that defined the genre now, but it was genre-breaking somehow,” echoes Melvin Benn, MD of Festival Republic, who was also there that night. “There’s no formula to how Bring Me The Horizon stepped up to becoming a festival headliner. It’s just their determination and our gut feeling.”

This was a teenage dream for Fish, who grew up in Newbury near Reading. Sykes, meanwhile, never thought he would do much beyond making music to mosh to. But this is the beginning of headlining other British festivals in 2023 and beyond. Its gravity matches Sykes’ newfound self-belief and compassion for himself. When someone changes internally, the tone of their voice and their facial expressions open up; you have the impression that you’re speaking to their distant relative rather than them. That is the difference between speaking with Sykes today and in the 2010s. He smiles frequently in LA — proper ones — and he looks like a new person.

To be able to say that you are the frontman of the only new headlining rock band in almost a decade gives Sykes the safety and reassurance that he never felt he had. For the first time he can relax on the throne he has spent 18 years building in a realm filled with conflict and dissenters. “It gives you that security of being able to sit back and say: ‘We made it.’ I could never see that before,” he says. “I always felt like we were hustling and conning and fighting to stay relevant. It always feels like we’re fighting. I think that’s from us being a hated and controversial band when we first started. It’s always felt like one slip-up and we’re out. Now we’re safe. We are a big band.”

Photographer: Lindsey Byrnes; stylist: Luca Falcioni

The third issue of Rolling Stone UK is out now and you can buy it here.