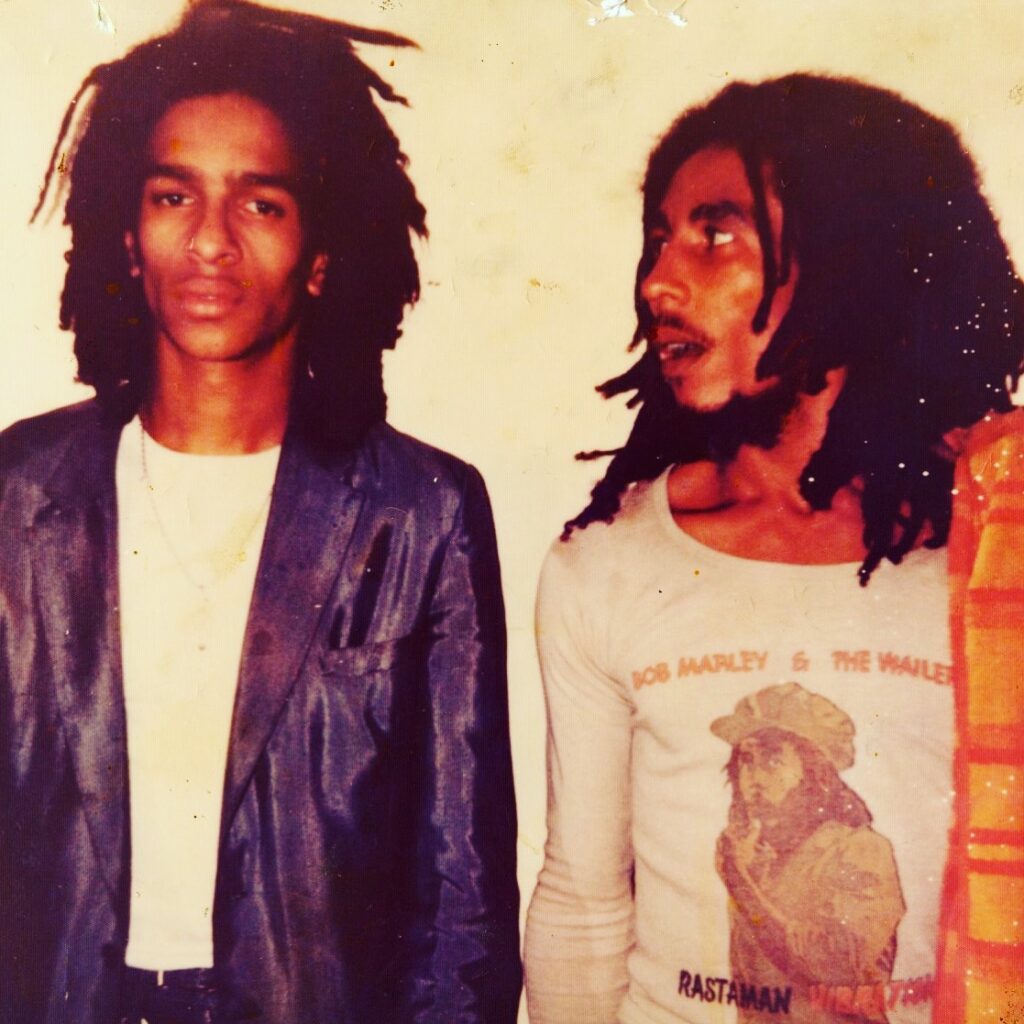

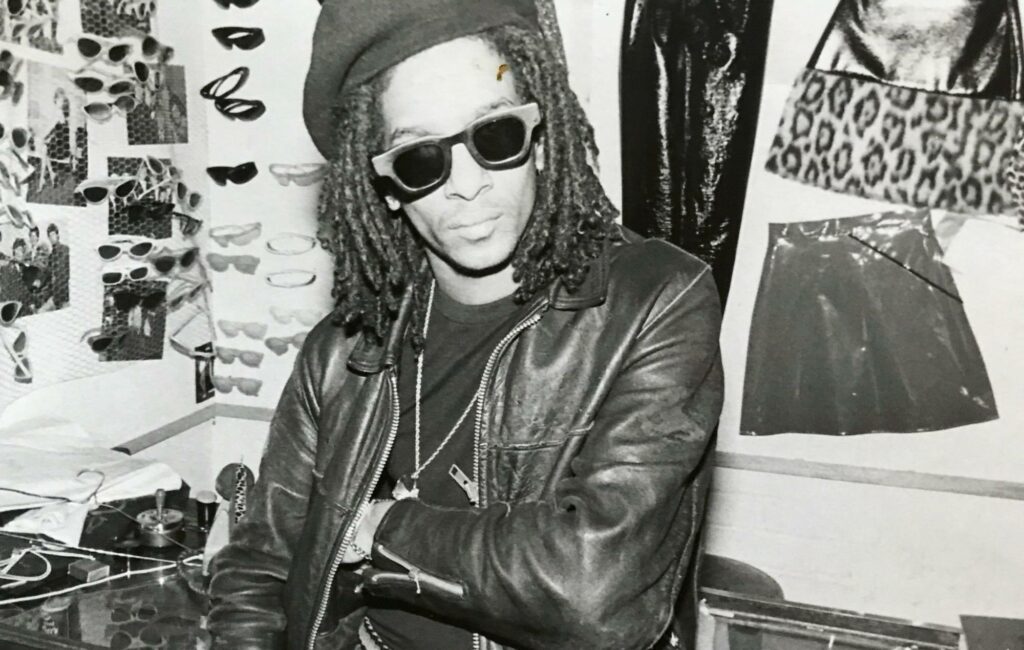

Punk legend Don Letts on telling his life story in new doc ‘Rebel Dread’

The first-generation Black British cultural mover, shaker, filmmaker, musician and raconteur shares his story in a new documentary, 'Rebel Dread'.

By Lee Campbell

Don Letts considers himself to be a chameleon: always moving, always changing. The story of his life growing up in London as a child of the Windrush generation has been made into a film — Rebel Dread, a title that was given to Don by punk band The Slits, a group that he attempted to manage. In the late 70s, Don brought the extreme worlds of punk and reggae into a shared space, before going on to direct high-profile music videos and form 80s band Big Audio Dynamite with ex-Clash musician Mick Jones.

Here, Letts, 66, talks to Rolling Stone UK about the lessons he’s learned along the way, including a life-changing gig watching The Who at 14 years old, feeling disconnected from his ‘roots’ while in Africa, and his friendship with The Clash, John Lydon and Bob Marley. And he even manages to throw a Rolling Stone UK exclusive into the conversation.

What would you pick out as your biggest challenges during a considerably varied life and career?

With hindsight, being an alien in a foreign country — the whole race thing, which I’ve tried to forget about, but society won’t let you, hence the title of my book, There and Black Again. While they’ve been arguing about Black and white, I’ve been digging all the colours in between.

What are you most proud of?

That’s a hard one, ’cos I’m as old as rock ’n’ roll [laughs]. I was born in 1956, dude. There’s a movie I did called Dancehall Queen. 1997 it was made, set in Jamaica, my first feature film, which was inspired by me first seeing The Harder They Come as a youth in 1972. With some punk-rock attitude, I reinvented myself as a film-maker and got to make this film, which is now legendary in Jamaican culture. Next to The Harder They Come, it’s Jamaica’s most famous film. That’s a big deal for me as a child of the Windrush generation.

With Big Audio Dynamite I got to write some cool songs with Mick Jones from The Clash. Also, [directing the video for] ‘Pass the Dutchie’, by Musical Youth. I remember when ‘Milly’s Tune’ got to No. 1 in the mid-60s. I remember how my parents’ generation felt. It gave them a sense of pride. ‘Pass the Dutchie’ did the same for my generation, which was Black and British. Up until that point, it was a confusing concept, but by this time it was beginning to make sense. And that video — as simple as it is — is kind of a cultural totem. White people dig it too, but for Black people it hits the spot.

My movie Punk: Attitude [2005], I am also really proud of that. I was sick of people looking back at something they identified as some weird anomaly that happened in the late 70s. My argument is, “No, that’s bollocks! Punk is an ongoing dynamic and it’s something to look forward to.”

Here’s an exclusive for Rolling Stone, too! Over the whole Covid thing, I like to do shit, man. The reason I do so many things, it gives me a reason to live, and it also stops me from facing anything vaguely real [laughs]. It wouldn’t be good to die before you’ve delivered, would it? Well, I’ve just finished my first solo album. I haven’t told anybody about that. It’s called Outta Sync, ’cos that’s how I feel these days. It’s facilitated by a couple of gentlemen called Gaudi and Youth. I’m buzzing about that, pulling this off at the ripe old age of 66! I’m really pleased with what I’ve done. It will be out some time around the fall of this year.

How was the experience of being a young, Black man living in the 60s and 70s in London?

Well, it was tough, but there’s that old adage about what doesn’t kill you makes you stronger. It’s because of the way that society dealt with people like me, not just me, not just Black people, [but] aliens in general. You either get fucked by it or it makes you stronger, and that’s what it did for me. I’m now this person who’s never short of a few words, and can stand my ground on my own, and that’s because society made me like that. And maybe if the Caucasian crew had been nicer to me, then I wouldn’t have been the kind of person I am today.

“I’ve just finished my first solo album. I haven’t told anybody about that. It’s called Outta Sync, ’cos that’s how I feel these days”

They say, out of pressure comes diamonds, but also a lot of fucking coal. I am a product of that dynamic. To counterbalance the socio-economic struggles of that time, we had the music. Back then, it’s all we had. Nowadays you’ve got a million ways to express yourself and a million ways to get alternative information. Music was vitally crucial to our existence and facilitated the opening of doors to people like myself to alternative worlds, universes and possibilities.

At school, all I was told was that 400 years ago I was a slave and should be glad to be here. But through music, I got to realise, ‘No, that’s bollocks! Actually, my civilization pre-dates yours, motherfucker!’ Seriously, though, joking aside, I think that people forget that music was that tool to facilitate social and personal change. I am a product of music. I am proof of that dynamic working, man. But we also had clothes. We turned that shit into an art form.

What do you love about London?

Well, the whole multicultural thing is obvious. But, back then we didn’t know it was obvious, it was just digging what these different people were doing, and being honest about it. Like, yeah, I like that Led Zeppelin riff! At a very young age, I decided I wasn’t gonna be defined by my colour. That’s what earned me the title of ‘The Rebel Dread’. It was given to me by Ari Up of The Slits, actually. For me it’s just been really liberating to be really honest about what I like, man. Some people are more comfortable in a herd or a group, and they are scared about being individuals. Back in my day, that was something to be celebrated.

How did that collision between reggae and punk in your life happen?

Accidentally. I got the gig at the very first punk rock venue. It was called The Roxy in London. It was 1977, so early in the scene that there were no punk records to play, so I played what I liked: hardcore Dub Reggae. Lucky for me, punks loved it! Even in between some of those tunes, I would slip in some songs that I knew were connected — MC5, The New York Dolls, Patti Smith,

Television. I get told, “Leave all that shit out — keep playing the Reggae!” Out of that interaction came what is described as this ‘punky-reggae party’. It was testament to the power of culture, bringing people together, understanding our differences. It works.

You’ve been close to a number of musical icons, such as Bob Marley and Joe Strummer. What advice sticks with you?

They never gave me advice. We didn’t have those sorts of conversations. You do it by example. If it has any sort of gravitas, it will resonate with a certain number of people, not necessarily millions of people, but enough people to get behind it and keep moving with it. It comes with this almost naive belief that music can change your life. I grew up on music that helped you be all that you can be. It was about changing your mind, not your sneakers! It wasn’t about making soundtracks for passive consumerism. It was about engaging with the world and your fellow human being. That’s what it was for me, and still is. You can’t spend your life on the dance floor. Eventually the music is gonna stop and you’ve gotta get outside and face reality. And guess what, there’s some fuckin’ great tunes for that, too.

The world needs leaders and spokespeople that can inspire us, and not be afraid to speak their mind. Do you think we are seriously lacking huge figures like that these days?

No. I think the dynamic has just changed. Don’t be offended, dude, but maybe we don’t need Caucasian heroes being saviours for this and that. I am not disrespecting the past. I just think things have changed. The nature of expression of protest, which is a big part of music, has changed. There’s lots of people protesting and plenty of protest music going on. It just doesn’t look like it used to.

In Rebel Dread, you describe the Notting Hill riots as “a beautiful day”. Can you give some context to this?

I respectfully qualify [in the movie] that it was a release. It was a release of pressure that had been building up for years and years. Over the years it has been interpreted as a race riot, a Black and white thing. It wasn’t. It was a wrong and right thing. Look at the footage. It’s Black and white youth together, fighting against the cops. By the nature of the time, yes, it was a predominantly Black carnival, but there were no Blacks and whites fighting each other; it was against the establishment.

We see a different side to John Lydon in the movie when you went to Jamaica with him.

I find it difficult to reconcile with the person that John was then and is now, but I forever owe the brother. He was the first person to take me to Jamaica, but I was so caught up with the whole thing of being in the land of my then heroes that I didn’t have time to think about where his head was at, which was obviously a very strange place Following the implosion of the Pistols, and the expectation that was placed on him to come up with something else.

In 1990, you visited Namibia and said it was the first time in your life that you had been in a totally Black environment. You described yourself as “the lost tribe”, and to pretend that you were anything else was “ridiculous”.

Yeah, I realised that I was disconnected from my so-called roots. It was embracing that difference, I guess. There was no going back to Africa for Don Letts. I’m going forward to some other place. I don’t know where that place is, and that taps into that whole Afro-futurism ethic, which I am very interested in.

You talk in the movie about passing on the energy. What’s that about?

Not many things come out of a void. I am part of an ongoing dynamic. Malcolm McLaren alerted me to that. Before punk rock even happened, man, I stumbled into his store in the early 70s and he explained to me that this counter-cultural thing that I was so enamoured with had a legacy and a lineage. And if I had an idea or was brave enough, that I could be part of this dynamic. It’s about tapping into a vibe and picking up the ball and running with it. There’s this energy that gets me going, it resonates with other people, and this thing continues.

“There’s this energy that gets me going, it resonates with other people, and this thing continues”

I am just glad to participate in the rock ‘n roll game. I don’t think ultimately I’ll even be a footnote. I would be happy with being a toenail!! It still gets me outta bed. It’s my life. You are always educating yourself. You have got to stay open to what the world has to offer, especially if it’s got a good bassline [laughs].