Dermot Kennedy: a universal truth

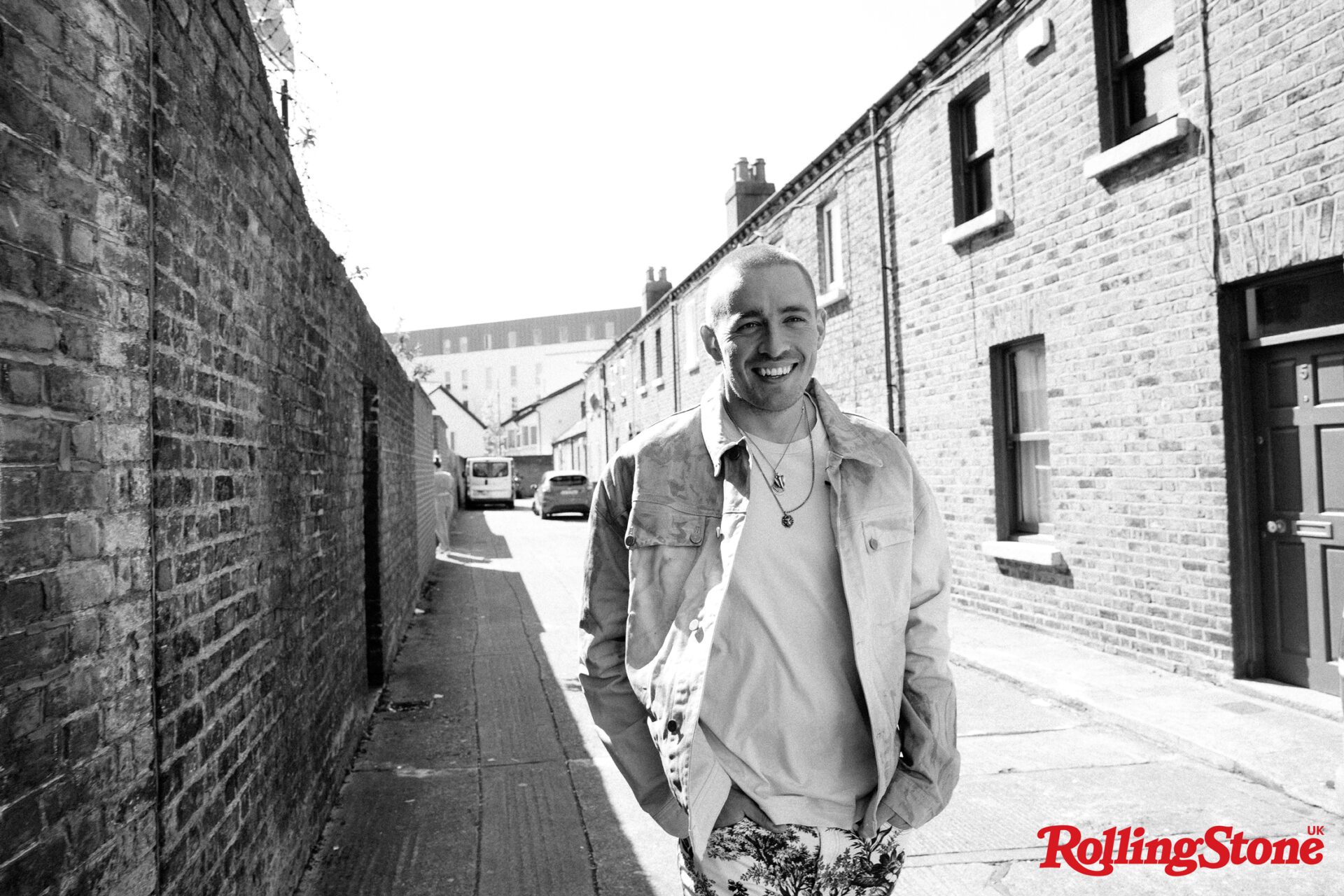

Dermot Kennedy wants to be as famous as his idols but is determined to keep his personal life private. In a saturated white male, singer-songwriter market, is being an Everyman a recipe for success? With poignant lyrics and delicate storytelling, the Irish musician is proving it can happen

By Hannah Ewens

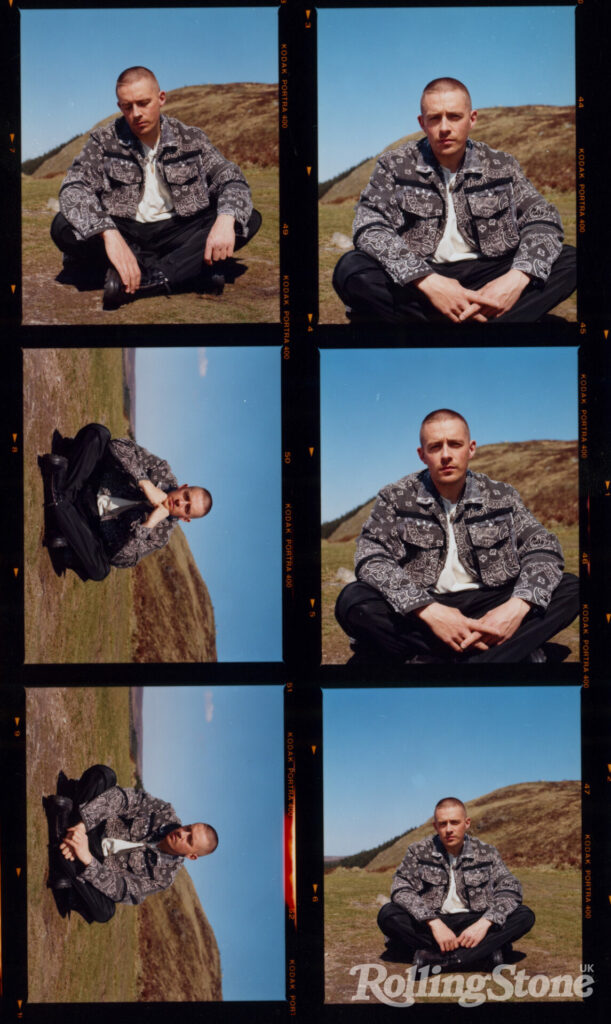

Boots and socks are taken off slowly and with a sense of purpose. Dermot Kennedy, who arrived home yesterday from New York, where he was working on his second album, once heard that touching your bare feet on the ground beneath you is a cure for jetlag.

We’re on the hilltop above Lough Tay — better known to Dubliners as Guinness Lake — surrounded by miles of burnt grass and tall thickets of trees that look like they belong in Twilight. “The earth — it’s like magic,” he says, when his skin meets the grass. “I don’t know if it’s true or not, mind.”

Kennedy came here semi-frequently as a child, but visiting now as an adult, this steep drop into an expanse of water makes him feel small and that his career isn’t so important. These moments are grounding for a man determined to be as prominent as his musical icons Bon Iver and Kendrick Lamar.

The singer-songwriter is known in the UK and overseas for his radio hits ‘Outnumbered’ and ‘Giants’, but here in Ireland he’s practically a national treasure. When we met at a golf club an hour’s drive from the lake, the barmaid was incredulous that Kennedy would come in here. He’s late, though — his manager says he doesn’t understand urgency. When he’s told something is a matter of priority, he’ll say, “All right” and be back half an hour later — which gives the staff time to gossip. When he does arrive and we’re about to leave, the barmaid runs across the tarmac in her heels and asks for a photo with him because her kids love him (she undoubtedly feels the same, punching the air as she returns to work after meeting the Channing Tatum lookalike with a grainy voice).

Connecting with people is increasingly Kennedy’s primary motivation. His first album, Without Fear, released in 2019, was a collection of tracks written over a decade spent at school, university and busking in Dublin. They were created just for him, rather than as part of any masterplan to win fame. When his hit ‘Better Days’ came out during last summer’s ongoing Covid restrictions, its simple lyrics about existing in dark times that soon give way to something brighter took on their own meaning for listeners: the song became about the pandemic. He realised then that he speaks to people through his songs; that songwriting is more than sitting at his piano in tears, his heart in his hands. His second album — due for release in September — has been written quickly and with his audience front of mind.

The pace demanded by the music industry is clearly a point of contention for him. He says of following up a debut, “If you think about it like a movie, it has an ending. And then someone is like, ‘No, do more, do more of that.’ Well, that makes no sense.” The requirement for songs to be three minutes long for streaming services makes him feel queasy. But he’s so ambitious that he concerns himself with marketing buzzwords like visibility, impact and growth. (“Until the second album comes out, you feel like you’re just slipping or fading slightly, whether that’s rational or irrational.”)

“I definitely had to work hard to get out of my own way. Because if the lyrics are the most special thing I do, you can go crazy, like sitting in cafes trying to be a writer”

— Dermot Kennedy

To hear a few bars of one of his singles on the radio, you could mistake him for someone else. But the lyrics are poetic and succinctly capture timeless emotions. Even when he’s singing about making out by a lake in ‘Kiss Me’, a song that sounds like he’s trying to capture The Notebook in 3:49 minutes, it’s well conceived and executed in a way that commands respect from the most cynical listener. His music is about life’s big three — love, loss and being present — and although it encompasses the easy blend of folk and hip-hop that British and Irish people have embraced en masse for a couple of decades, there’s something unique in the way he grasps for truth. They’re the sort of universal songs specific enough to feel that he is speaking to you, but whose lyrics are subtle enough to apply to multiple situations you’ve found yourself in; it’s music that’s chosen by a couple for their first dance or by their loved ones at their wake.

He’s been called the Irish Ed Sheeran and Rag’n’Bone Man by critics, but Dermot Kennedy is a distinctly different artist. Where Sheeran has started evoking vampires and Bronski Beat and Rag’n’Bone Man never stepped out of the shadow of his ubiquitous and drab ‘Human’, Kennedy has crept in quietly through the back door and into the UK charts, commanding that you listen in and feel.

“There’s so many people trying to do what I do: I’m a white, male singer-songwriter with a guitar, you know what I mean?” he admits. “That is not a unique concept and so I’m trying to be different.” Knowing that his lyrics are part of his appeal, he pays special attention to them. “I definitely had to work hard to get out of my own way. Because if the lyrics are the most special thing I do, you can go crazy, like sitting in cafes trying to be a writer.”

Plenty of his contemporaries’ music is too generic — there is a coterie of chart-topping musicians similar to Sheeran and Rag’n’Bone Man whose music exists to appear on gym playlists and Love Island — and Kennedy believes this more than anyone. “If you’re lucky enough to work in the world of art and culture, it’s such a waste of everyone’s time if you’re just going through the motions,” he reflects. “That’s why I listen to hip hop all the time; there’s sincere emotion in it.” That also goes for performing, as he forces himself to relive those emotions: “Even when I’m on stage, I’m only thinking about the past and the future and what you wish it could be. You spend so little time present as a musician, which is nuts to me.”

His most successful songs to date are more on the nose and relatable but they are at risk of Kennedy turning his back on them. It’s unlikely ‘Giants’ will appear on setlists again: “I don’t know how much I love it, but it is reassuring to me to know there are lyrics in it like ‘And my hand fit in yours / Like a bird would find the breeze.’” He doesn’t mind trying to construct obvious hits — he considers it part of the game he must play — but understands that people will judge that impulse. “Being a creative and an artist, there are a lot of words that seem scary or taboo almost: ‘accessible’ or ‘commercial’. For me, the word I’ve come across that doesn’t feel so bad is ‘direct’,” he explains.

The reason he will try to speak to the broadest audience possible is because he wants to be known. In the same breath, he is private and will look away while answering a question that could reveal something personal — like where he stayed during the pandemic, for example.

How does he balance his professional desire to differentiate himself from those other white, male singer-songwriters and his need to reject a personal and more intimate narrative? “I’ve always been resistant to the idea of celebrity,” he says, taking time to mull this over, though I sense he’s already given it a lot of consideration. “There’s certain things I know I could let go, even in interviews in the past, that would add to my story and things I know would be beneficial to my career. But I think of all the people in my life. If they were to read it, they’d be like, ‘Interesting, I thought that was just a thing between us.’ I can’t… because what’s it worth, you know? You can’t give that stuff up.”

Of late, life has felt too easy for Kennedy. Last year he took a road trip across North America because his everyday experience had become too smooth, too sanitised. “It got to a point where every place I stayed in was quite nice. Every studio I was in was really good. Everything was ‘quite nice’. And I was like, ‘This isn’t interesting.’ I just took this trip because I wanted to have to go out to the car at, like, three o’clock in the morning in Utah and not know if there’s snakes, you know what I mean?” He laughs and adds: “Just something, some kind of excitement.”

This extravagance is still new for him — his ‘authentic’ route to music through hard work and busking is a romantic origin story. Growing up as a child in Dublin, music was a passion. Perhaps unusual for a young boy, he gravitated towards the love songs of Everyman acoustic singer-songwriters Damien Rice and David Gray (in Ireland, Gray’s 1998 White Ladder remains the best-selling album of all time by quite a measure). From the age of 10 or 11, he learnt guitar and would sit at his parents’ piano and write for hours — sometimes the magic would show up, and sometimes it wouldn’t, but there’d be no agonising about that. He just knew it felt good and warm to write words and sing them.

“Even to this day, it’s hard for me to write when I know that someone is in the room, no matter how much I know them, no matter how much time they give me, it’s just hard for that pure part of my brain to come out,” he confides.

“Ireland has a very healthy music scene but during the pandemic it was ignored badly. As a country, we love talking about it and celebrating Van Morrison and Bono. Cool, if you want that to happen again, we really need to nurture that”

— Dermot Kennedy

His obsession, though, was football. He played seriously, told by adults that his future lay in the Premiership. This took the pressure off making music — he always thought he’d be a footballer and have music as a hobby.

Living this double life as one of the lads and an emotional teenage songwriter never caused him trouble. “There wasn’t much for people to take the piss out of because all I was doing was making songs,” he says of his football friends. “Don’t get me wrong, like, I definitely separated the two. There was one time in the football dresser where they were like, ‘What do you write songs about?’ And I was like, ‘Not in here, I’m not doing this.’”

Football is still an important part of his life — for the past few months spent in New York he was playing regularly for a team. “It gives me a clarity of mind that I just don’t get from anything else, even music,” he says. “You know, the way some people say they feel just so free on stage and feel weightless? I get that playing football.” There’s something meditative about it. I mention Haruki Murakami’s memoir What I Talk About When I Talk About Running, in which the Japanese novelist explains his daily practice of long-distance jogging to clear out his mind before writing. Kennedy has read it and espouses that artists need to have time without distractions or art, and phones, in particular. “When I put my phone away for a day or two, I can feel my brain going back to the way it was when I was 18, your mind finds that natural rhythm,” he says, noting that even though he knows it’s wrong, his jealousy of other artists is stoked through social media use.

At 17, Kennedy finished school and reluctantly went to Maynooth College to study classical music; it was mostly a back-up plan to appease his parents. He was already busking on Dublin’s Grafton Street and playing bars in town: his dad would have to take him to open-mic nights and plead his case at the door, promising staff he’d not drink. The local gigging continued throughout his early to mid-twenties. He avoided industry offers or taking on a manager, though the interest was there.

“My advice to younger people is, just be so careful who you trust and what direction you go because you need to know who you are as an artist,” he says. “Everything will try and steer you away from it. You have to be so fucking solid in the creative vision that you have. And I was lucky enough to have that, partly because no one cared for so long and I had to be patient. From when I started playing in the street till now is, like, 14 years.”

His luck changed quickly and without warning. Despite the scrutiny currently placed on streaming services and their low payment to artists, Kennedy was one of the system’s winners. His intricate piano ballad — and arguably most special song to date — ‘An Evening I Will Not Forget’ was selected by Spotify’s algorithm Discover Weekly. He was at a show he put on for himself at Servant Jazz Quarters in London the day this happened. “A bunch of people came up to me and said they’d bought tickets that day because they’d heard my song on Spotify,” he remembers. “I was already hooked on checking my amount of listens every day and so I went on Spotify, and I think I’d gone from 10 listens a day to 50,000 because of this Discover Weekly playlist. I organised a meeting with Spotify and other people by myself. I really did grab that moment.”

Shortly afterwards, he had tens of thousands of pounds in his bank account which allowed him to be selective about who he would work with. He ended up signing with Universal because he felt they supported his vision. “You gotta be careful with this stuff. You go above all the label bosses and it’s ultimately shareholders, right? You’ve got to be conscious of the fact that you are a product in that world. Certain people will not care how you feel and don’t have certain amounts of patience,” he says, pragmatically.

It often feels in this political economy that there’s little in place to support art being made. “Ireland has a very healthy music scene but during the pandemic it was ignored badly,” Kennedy notes. “As a country, we love talking about it and celebrating Van Morrison and Bono. Cool, if you want that to happen again, we really need to nurture that.”

Of Ireland’s newer musicians, fellow Irish musician David Balfe is someone Kennedy would like to collaborate with. Balfe’s 2021 self-titled project, For Those I Love, about his friend’s suicide and the process of grieving for him, was named Rolling Stone UK’s best album of that year and recently scooped the Album of the Year award at Ireland’s Choice Music Prize. “I’m drawn to someone doing something as authentic as that and someone as reluctant as that to chase fame,” says Kennedy. “I think those are the things that should win, in a strange way.”

Kennedy’s local pub is an old, ivy-covered establishment filled with oil paintings, wooden panels and pewter tankards. Kennedy’s mother and father, John and Eileen, stroll peacefully in 15 minutes or so after our interview has finished.

“I’m happy to share vulnerable parts of myself, but I’m not happy to use certain parts of my life and memory to fast-forward my career. I’d like to think you get rewarded by the universe if you hold on to certain things and just put all your heart into the art you make”

– Dermot Kennedy

Being around his parents makes their qualities appear clearly in him: he too is unassuming and quiet but also frequently amusing or amused. Family is of paramount importance to him, so he intends to keep Ireland as his base forever. He recently purchased his first house nearby and his parents have helped to renovate it. Apparently, he dreams of leaving music behind, buying this pub and becoming its landlord — although his parents weren’t supposed to tell me that. Being away has made him reassess how significant this area is to him. Taking over the pub would mean having his feet in the grass in a permanent way.

The title of Kennedy’s new record is Sonder, a word that means the realisation that each random passerby is living a life as vivid and complex as your own. The lead single ‘Something to Someone’ is a rousing pop song about knowing that you’re loved, one built to fill stadiums and festival fields.

“There’s a phrase in Ireland that if you see someone that’s down on their luck or anybody in trouble, you say, ‘Oh, some mother’s son,’” he explains. “‘Something to Someone’ feels similar to me: no matter who it is, someone somewhere cares about them infinitely.” Who knows if it’ll end up being played live in five years: “I like the little songs that are in between the singles. That’s when I feel I get to really, fully express myself.” A track named ‘Innocence and Sadness’ feels like this album’s ‘An Evening I Will Not Forget’, he thinks, by which he means it’s special. They’re “the types of songs you have to fight for” despite the fact they’re the ones that make and keep you a legitimate artist.

I think that’s where Kennedy has met success with his strategy so far: if you create strong but delicate work that people feel enough ownership over, they’ll not demand more of you. If he’s already speaking for so many, who he is becomes less important than the universal truths he gestures toward.

His parents have been at the pub, sure, but that’s not oversharing, this is just the rhythm of his life. Plus, his dad would have come down for a pint regardless. “I’m happy to share vulnerable parts of myself, but I’m not happy to use certain parts of my life and memory to fast-forward my career,” Kennedy says, as he settles on his stance about privacy. “I’d like to think you get rewarded by the universe if you just hold on to certain things and just put all your heart into the art you make.” He thinks about this for a second and then makes a face like he’s stepped backwards to look at the view. “Maybe I’m wrong but I hope so. And if I’m wrong, I can live with it.”

Dermot Kennedy’s second album, Sonder, is released 23 September 2022.

Taken from the forthcoming issue of Rolling Stone UK. Buy it here.