2022: the year that ‘indie sleaze’ wasn’t a thing

A slew of articles in January promised that the indie revival was just around the corner. But as the year draws to a close, it’s yet to materialise. What gives?

By Selim Bulut

As 2022 dawned, I was told that one trend would define the next 12 months: indie sleaze.

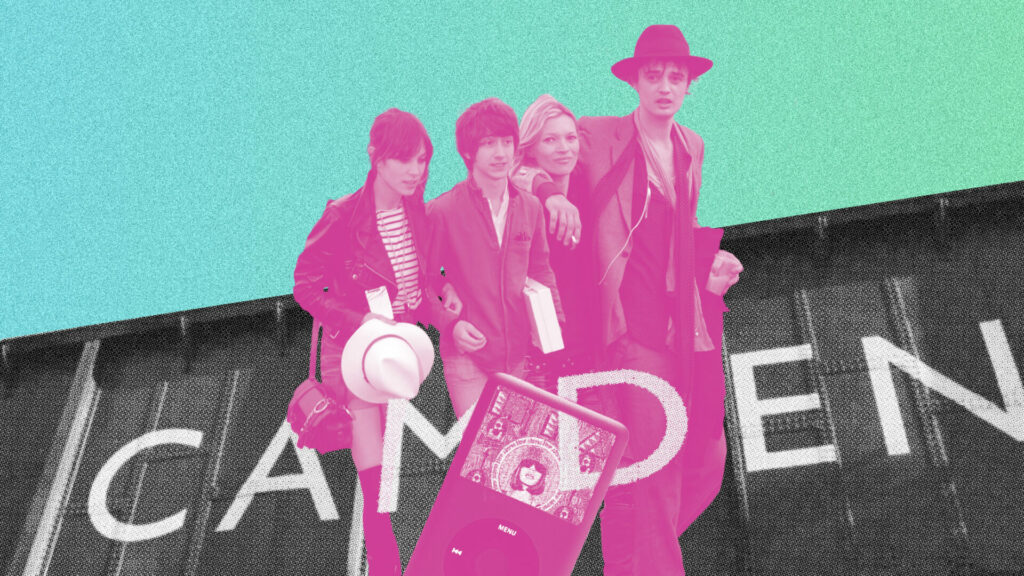

Articles in Vogue and Elle, via the Guardian and GQ, insisted that the sounds and styles of the 00s indie scene were due to make a comeback. Clean living was out, elegantly wasted was in. Girls would look like Kate Moss or Agyness Deyn, boys would dust off their leather jackets and pray they could still slide into skinny jeans. After two years of Covid lockdowns, we were all yearning to be dangerous, debaucherous, and downright messy. On nights out, we’d turn into part-time Cobrasnakes, doing flash photography on point-and-shoot cameras, preserving every mascara-smudged memory in 5.1 megapixels. It would be our own eternal Tales of the Jackalope. It would be like the Lehman Brothers never collapsed.

But the year is drawing to a close now, and this indie sleaze revival has yet to pass. What gives?

Well, it could be because this ‘comeback’ was never real in the first place. Most of the articles published in January relied on the same two sources as proof of indie’s imminent return: some videos by TikTok trend forecaster Mandy Lee, who insisted that there was an “obscene amount of evidence” that the old hipster aesthetic was returning (mostly, models were wearing wired headphones as a fashion statement), and the growing follower numbers of an Instagram account, @IndieSleaze, that curated images and videos from the era. Fairly flimsy stuff.

But while a full-blown return to Madame Jojo’s circa ’07 never came to pass, indie’s influence wasn’t totally absent this year. Paramore cited Bloc Party as an inspiration on their new album This is Why, while Rina Sawayama worked with the band’s original drummer Matt Tong on her second album Hold the Girl. The Strokes, the Yeah Yeah Yeahs, and M.I.A. all played major European festivals. Wet Leg felt like Britain’s first genuine ‘hype band’ in years. In the summer, Gordon Raphael, who produced era-defining albums like Is This It and Room on Fire, published a memoir documenting his time on the scene. Meet Me in the Bathroom, Lizzy Goodman’s oral history of New York City’s drug-fuelled, cash-flush, politically incorrect 00s indie years, was turned into a documentary. Even ‘landfill indie’ bands like The Kooks reported that they were playing to their biggest crowds in years.

So if indie really was back in some form, why did reports of this revival leave me feeling so hollow? It could be the ‘indie sleaze’ phrase itself. Although ‘indie’ was always a fairly generous term, as applicable to a no-mark band releasing 500 copies of their debut seven-inch single as it was to a major label pop group like The Killers, there were still different subscenes and warring tribes that fell under the wider indie umbrella. Grouping these related-yet-separate factions together steamrolled a lot of those original distinctions, reducing what were genuinely vibrant and creative DIY communities to inert caricatures.

“The indie sleaze revival felt so small-time… Where was the new ‘Paper Planes’, or ‘Last Nite’, or ‘Giddy Stratospheres’? Why wasn’t I seeing club kids in gold American Apparel leggings, or those Peter Pan lace collar dresses Alexa Chung used to wear?”

It could also be that the indie sleaze revival felt so small-time. Noughties indie was probably the last time a subculture based primarily around rock music held so much sway in the mainstream, seeming to be in conversation with art, fashion, film, television, magazines, internet culture, and nightlife. If a cool band or an it-model wore a certain outfit, a knock-off would usually appear in regional branches of Topshop a few months later. A buzzy new act might find their song in an episode of Skins, beamed into the living rooms of some 1.5 million people. You could go to almost any university city in the UK and find an indie disco, modelled on parties like Erol Alkan’s weekly clubnight Trash, playing new songs and crossover anthems from rock bands and electro acts. Indie sleaze was hardly on the same scale. Where was the new ‘Paper Planes’, or ‘Last Nite’, or ‘Giddy Stratospheres’? Why wasn’t I seeing club kids in gold American Apparel leggings, or those Peter Pan lace collar dresses Alexa Chung used to wear?

Still, I can understand why so many writers hoped they could will this revival into existence. It was certainly more fun back then — the bottom hadn’t yet fallen out of the economy, at least not entirely, and cities like London and New York weren’t totally gentrified and could still just about be an artistic playground for young and creative people (I’m sure the longstanding residents of Hackney and Brooklyn were less thrilled about this). And while I don’t really buy that the Noughties were a simpler time politically (I associate much of my teenage years during this period with the War on Terror and the rise of the BNP), it seemed easier to tune a lot of things out.

None of this really points to proof that a younger generation has suddenly taken to indie, though. Instead, it seems to be more about older millennials becoming less enthusiastic about new music, more alienated from the youth culture around them, and retreating to the relative comforts of the recent past.

But you can’t go back. You can’t go to a warehouse party when it’s been converted into a mixed-use residential, retail, and office space. You can’t smoke on the dancefloor. You can’t debate the merits of the Mystery Jets’ new album when the sterling is collapsing. You can’t get EMA. You certainly can’t use your EMA to buy M-kat on eBay. You can’t start a band called Gay for Johnny Depp.

Indie sleaze can’t solve the problems of the present. To borrow a popular phrase from the time — don’t believe the hype.

Taken from the December/January 2023 issue of Rolling Stone UK. Read the rest of our essays reviewing 2022 here.