Apologise, I won’t: get an exclusive first look at Fat White Family’s new book

In a Rolling Stone UK exclusive, we take a first look at 'Ten Thousand Apologies', a no-holds-barred account of infamous squat rock degenerates Fat White Family

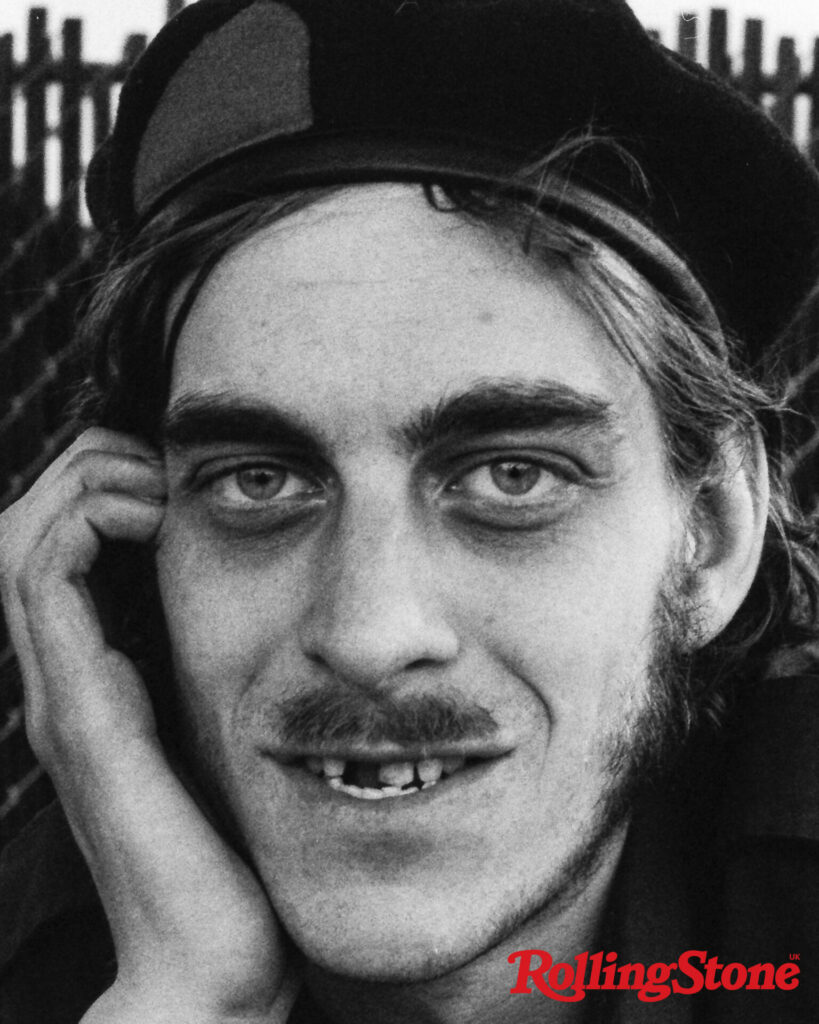

Covering not just the ten-year history of Fat White Family, but also singer Lias Saoudi’s family roots in Algeria and his life growing up in Northern Ireland with his younger brother Nathan, Ten Thousand Apologies is unapologetic. The book jumps from evocatively written third-person prose (alongside his bandmates, Saoudi’s parents both have POV chapters) to Saoudi’s bluntly hilarious recollections of the band’s numerous acts of depravity.

The singer writes with a delicious turn of phrase (DJ/producer Mark Ronson is described as having a voice which “sounded unfinished, like it was stumbling over its shoelaces on the way out of his mouth”) and a stand-up’s sense of timing. It’s a jaw-dropping rollercoaster of tragi-comic mishaps and gargantuan drug consumption, the lion’s share of the latter driven by the wayward presence of his songwriting partner and Fat White Family’s dictatorial musical director, Saul Adamczweski.

The book states at the start that it’s a “fabricated, reimagined and embellished” version of events. As such, you might think that stories such as Saoudi being arrested after a bandmate performed oral sex on him at a gig in Sicily is an exaggeration but turn the page and there’s photographic evidence of it happening. In fact, almost every paragraph has a barely believable, hair-raising anecdote within it, such as the time Adamczweski spent several days believing he was possessed by the spirit of 1940s occultist Austin Osman Spare and could control his bandmate’s mind. Or when he locked the entire group backstage on the night of the Bataclan attacks — not for their safety, but because he’d arranged to meet his dealer there.

Rolling Stone UK sat down with Saoudi over a hangover-combatting Aperol Spritz to separate fact from fiction.

At the start of the book, you claim everything is embellished. But did the story need much exaggerating?

That’s more to get us off the hook if there’s any public outrage. There’s a cancellable offence on every other page, so we put a disclaimer at the beginning. I just finished reading the whole thing yesterday. I was anxious about that halfway through and then by the end I was just quietly glad that I’m not dead. I don’t think that’s hyperbolic; it was a horrible time.

It all makes for an entertaining read, but you had to live it. Having to sit down and remember some of that stuff must have been difficult?

I found that agonising at times. When I was writing my own passages, it’s fine, but when it got to knuckling down to the whole text with [co-author Adelle Stripe] and you’re reliving these viciously puerile periods where it’s basically: I’m just going to tell you all the most embarrassing things I’ve ever done in a row. Then having to doctor that for style to see if it reads well. That was really quite testing — but it was cathartic. It made me look at different relationships in my life and there were obvious patterns of behaviour and all kinds of ill-informed decision-making and you can see how it’s connected. In that sense, it was healthy, but it was a bit of a fucking grind sometimes to get it down.

It’s pretty near the knuckle. You write about things like Adamczweski moving into a crack house in a very matter-of-fact way.

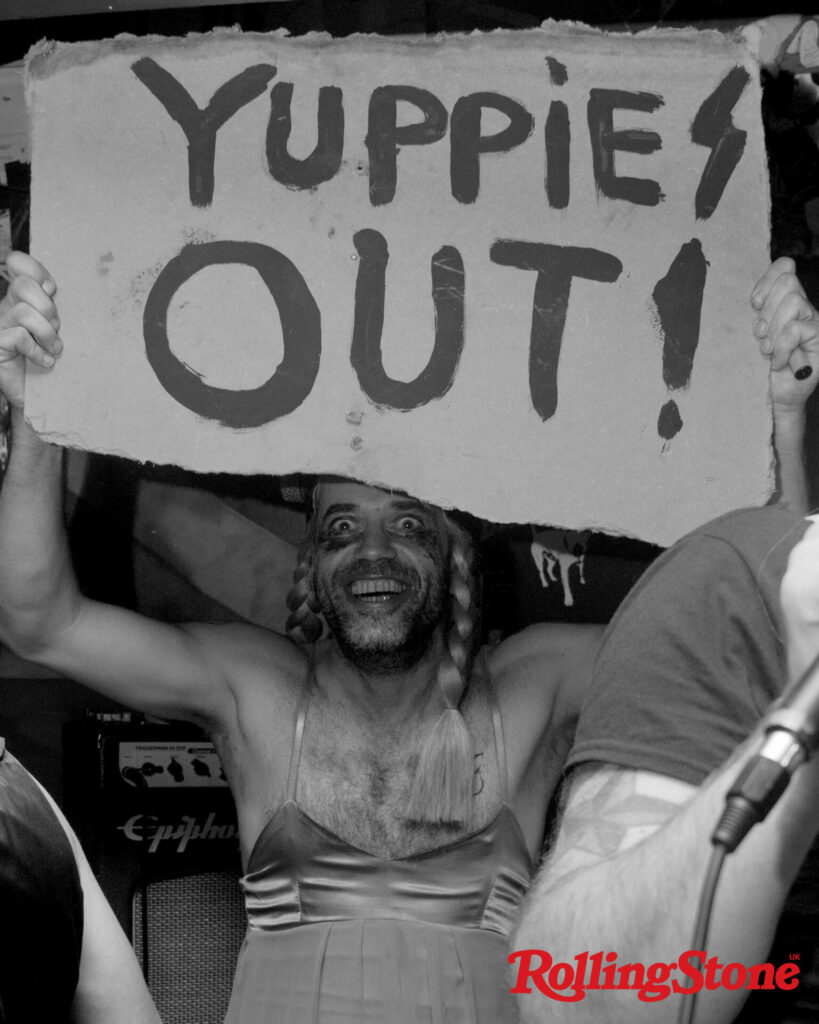

It really got to me in the past few years, this kind of fetid, paranoid state that everybody who’s in any way in the public eye lives in now, where everybody is ultra-cautious about putting a foot wrong. This project was the opposite of that. That was the whole ethos: to rattle the f***ing cage as much as you possibly can out of sheer boredom and animosity for the banality that’s been rammed down your throat for years. I thought maybe that would be a good way to remedy that: let’s just put the whole thing on a big plate and there you go. It’s flawed in the extreme and some of it’s not really excusable, but I would hope at least it was explicable.

You tell the stories with a lot of humour, though, like the time you’re having a panic attack backstage and a meth addict gets into bed and offers to suck you off.

For 20 dollars, yeah. And then all our gear got robbed. It was just non-stop like that. I mean, the amount of stuff that we had to cut out of the book.

What did you have to cut out?

Huge amounts. I’d have to wait until most of the people involved are dead before everybody gets the redux version because it would completely ruin everybody’s lives. This is the rated PG version.

Obviously, he was in the throes of serious drug addiction at the time, but Adamczweski is painted in a very bad light on multiple occasions. Did he have anything to say about that after he read it?

He was a surprisingly good sport about it. I think it was a difficult read for him because a lot of that stuff is dark and painful. He could have been the one person that could have just been, like: “No, I don’t want that out in the public sphere.” And he would have been well within his rights, but he was more like, “Nah, it should be nastier. It was much worse!” If he had a criticism, it was that it’s not dark enough. It’s also getting the full picture of a character.

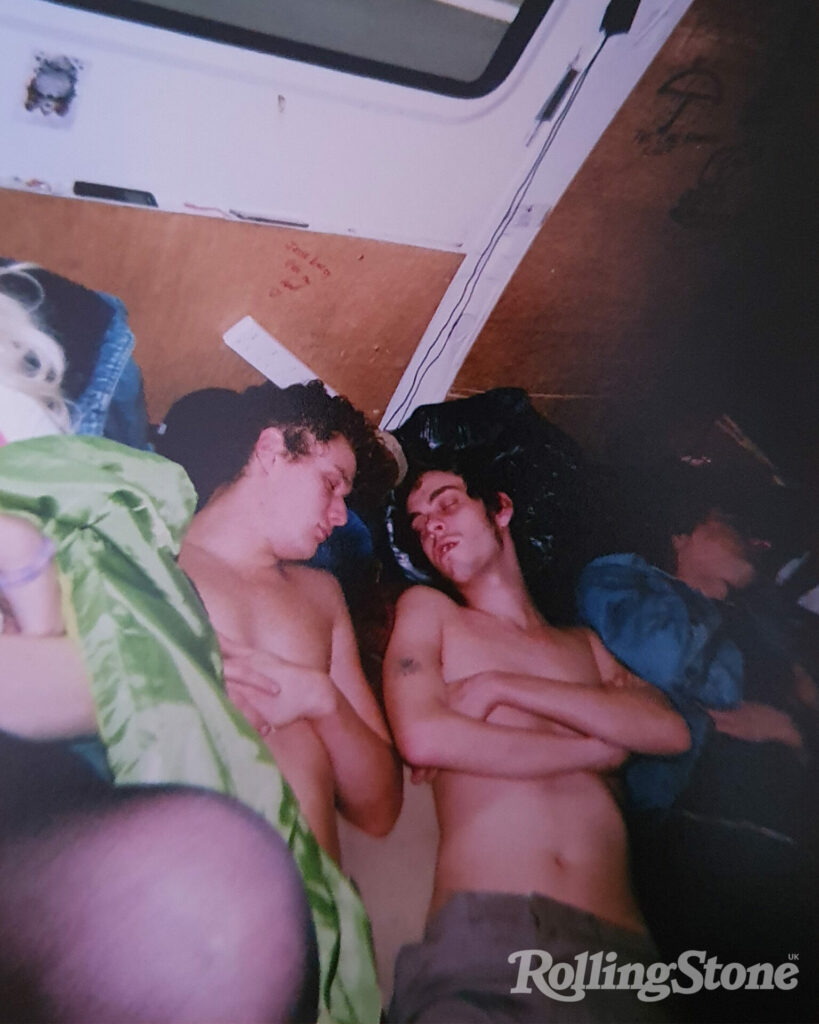

I think people’s idea of what it is to be in a band that’s had a little bit of success or a following is from another era where guys in bands used to actually make a bit of money. We’d go and play, like, Brixton Academy, but then you’d just go back to whatever crack hovel it was that you were stewing in at the time. It was an utterly turgid, squalid existence off-stage. It was an absolute fucking mess. Nobody got out of it unscathed.

Given the amount of drugs involved, it’s surprising Adamczweski even remembers a lot of this stuff.

It was one of them things where you’re waiting any minute for the guy to die, in quite a real way. Part of you would have been all right with that! The worst part of you. At least it would be an end to the tale. At least we would have sold a few copies of that second record!

The extreme honesty in the book does feel like an extension of Fat White Family’s warts-and-all ethos. Do you find that bands these days hold themselves back somehow?

There was long tradition of it in the ’60s and ’70s that ran dry. That spirit of radical honesty, where people are willing to put themselves on the line to turn themselves into living art. People don’t have that kind of licence any more, especially young people who’ve grown up with this hyper self-awareness that goes with social media.

It seemed unusual to me that nobody was engaged in that kind of guerrilla cultural warfare back in the early 2010s. It just seemed obvious that people were owed something hideous and repulsive. The economy was collapsing and the environment; it couldn’t get any more toxic and everybody’s making this like, nu rave s**t. It’s just posturing. Give me something that reflects the insidious, incestuous, perverse state of the current climate that we’re all feeding off. Isn’t that the point of art and culture, to offer a meaningful reflection of where we’re at? We’ve completely stumped ourselves by replacing it with politics, which is where we’re at now. That’s the hip thing: what kind of an activist are you? Give me a f*****g break. It’s just narcissism as far as the eye can see. I figured doing a lot of drugs and living in a toilet was the honourable thing to do faced with that deck of cards.

“Isn’t that the point of art and culture, to offer a meaningful reflection of where we’re at? “

As a music fan and a reader you get a vicarious thrill hearing about that stuff, but there’s a very real human cost to all of it.

Yeah, my parents didn’t find it an easy read. It wasn’t a barrel of laughs for them, I don’t think. But that’s the thing: it was horrible, but it was also a fucking laugh. The chuckles just kept rolling.

Is there a level of hypocrisy that we talk about mental health and the wellbeing of performers, but then we also love to hear all the gruesome details about the darker side of it all?

I think that’s always going to be the case. That’s part of your job, isn’t it? You’ve signed up for that and you can’t really complain when it all goes west because you have decided that everyone can live vicariously through you for a bit.

When Adamczweski enters the book, you talk about him being diagnosed with behavioural problems as a child. As a teenager he was briefly signed to a major label [as frontman of post-Libertines outfit The Metros] and then dropped. Throw crack and heroin into that mix and no wonder things turned out the way they did.

Well, yeah. He’s obviously a headcase, for want of a better word, and then he’s thrust into the limelight by Sony Records, given all this f*****g money and told he’s gonna be this and that, and then the next minute he’s dropped like a bad habit with an even worse cocaine habit. That’s that guy fucked. Obviously, I know all about Saul, his background and everything, but when you actually read it all and it’s linear, it’s like, OK, I understand now… I might not forgive, but I understand!

Does being in a band give you licence to be an addict to a certain extent?

Saul would have been a f*****g junkie whether he was in a band or not. I think that’s a pretty fair assumption. But he’s got the music, thank God. There’s a certain amount of moral luck that goes with talent. People will tolerate all kinds of f*****y because you’re unnaturally gifted in some way. There’s a lot of umming and ahhing about that in the culture, where it’s, like, how do we separate the art from the artist? It’s not really any of your business. It either sounds good, or it doesn’t, and you don’t really have a say in that. It’s a sensual response, it’s not a science. The thing is its own justification. I think that’s interesting when you get characters like this that are utterly wayward, but they have some kind of currency. The depraved suddenly have a voice, and God bless that.

The chapter where your show at The Cigale in Paris is stopped on the night of the Bataclan attack is particularly bizarre. Adamczweski locks you all in the dressing room but it’s only because he’s arranged to meet his drug dealer there.

Yeah. People were saying online that they’d hit up the wrong band. That was f*****g weird, but at the time it didn’t register with me. I just wanted to get high and sleep with French girls. I was, like, “Really? We have to stop the show? How can I get cocaine and get laid?” This is how far up your own arse you are in that state. You’re completely numb to what’s going on. It wasn’t until we got home, [that] it was, like, man, that was seriously hideous. It’s absolutely brutal and it was just the other venue.

It could have been your gig.

I did think about that. We did wonder if they knew that there’s a couple of Muslims in the band. Maybe they Googled it? Me and Nathan tried to take credit for the fact that we’re all still alive. Like, it’s fucking Algerians, they’re our comrades, so they’ve left us out. That or they were bang on [Fat Whites’ support act] Wolf Alice.

What did you learn about yourself writing this book?

I’ve learned that I like writing. It’s great. You have weapons in your head, you can manipulate people’s brains in another way that you can’t with just a pop song because nobody can hear the fucking lyrics. I’d definitely like to write books as I get older. If I live long enough.