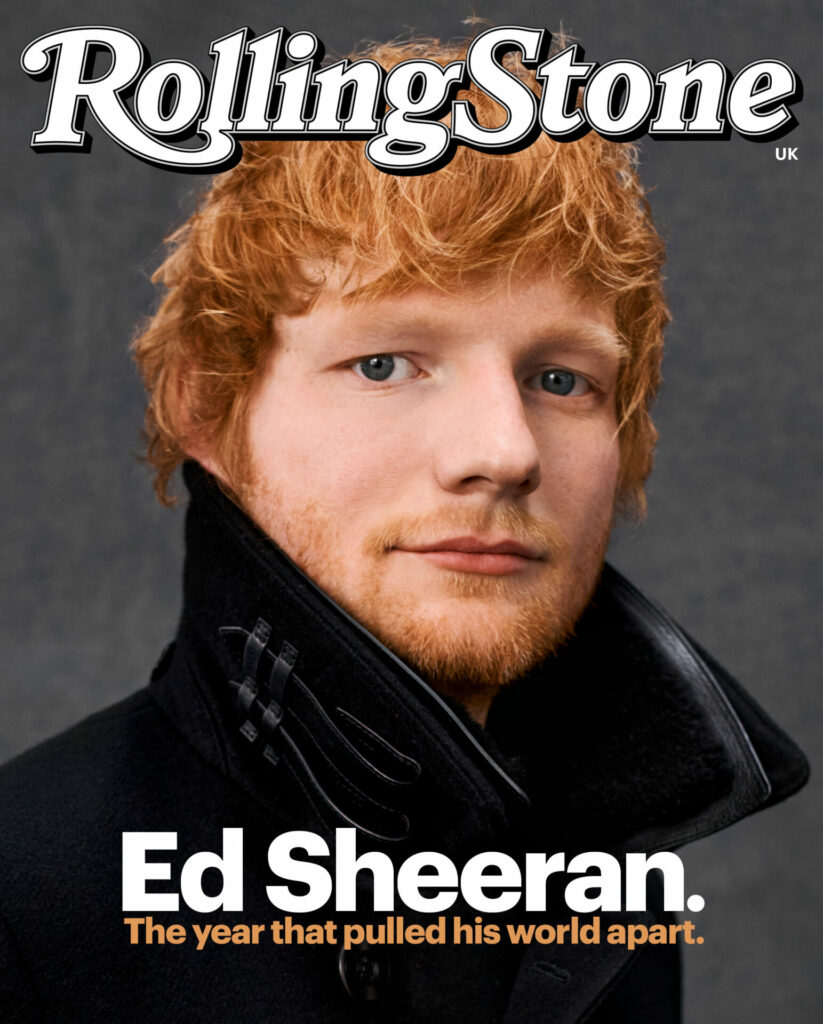

Ed Sheeran: the year that pulled his world apart

When Ed Sheeran became a dad, his ‘party boy’ days ended. Then tragedy struck, forcing him to face his hidden dark side — and hit his hottest creative streak.

By Brian Hiatt

In case there’s any doubt, Ed Sheeran is well aware of the fact that he’s … Ed Sheeran.

“I’m not an idiot,” he says, early in our acquaintance. “When you say in your office, ‘I’m gonna go and interview Ed Sheeran,’ you must get sneers. I’ve always been that guy.”

The state of being that guy, at the least the public version of him, is a paradoxical one. Sheeran is, on the one hand, unquestionably among the 21st century’s very biggest global pop superstars. That’s why he’s 11,000 miles from home right now, in the fenced-off, tree-lined backyard of a rented bungalow in Auckland, New Zealand, lounging in the shade his complexion demands (“I live in the shade”), under blue-gray skies. Later this week, he’ll play to some 100,000 people over two shows here. His last tour was the highest-grossing of all time, until his mentor, Elton John, surpassed it; this one, somehow slated to last five full years, may well reclaim the title. He’s one of the top five most-streamed artists ever on Spotify, a statistic that doesn’t even include his “hobby,” all the hits he’s written for other artists, from Justin Bieber to BTS.

But Sheeran is convinced that, in certain quarters, his achievements and talents — his elastic voice, his endless trove of hooks, his freaky, human-playlist capacity for cross-genre metamorphosis, lately extended to Afropop, EDM, and reggaeton — don’t seem to register. In those eyes, he’s a ginger-haired interloper, a vaguely hobbit-y mortal who ascended into the realm of pop godhood via some kind of cosmic error, and then refused to leave. “I was the butt of jokes before this,” he says, “and I’m the butt of jokes now, and it’s not necessarily just my music.”

It’s a mid-February afternoon, late summer in this hemisphere. Sheeran’s wife of four years, Cherry Seaborn, and their two daughters — Lyra, who’s two, and Jupiter, eight months old — are inside the house, square in the middle of an upscale suburban block. The whole family is spending a couple of months in New Zealand and Australia while Sheeran commutes to his stadium shows. There’s an eerie normality to his offstage existence here, as if he’s swapped lives with a prosperous Kiwi dentist. “Yesterday,” Sheeran says, “we cooked, we watched an episode of The Simpsons, went to bed.”

Lyra, who’s emerged for some snuggle time, is eyeing a blue plastic wading pool on the Shire-green lawn. “As soon as Daddy’s finished the interview, I’ll go splashing with you,” Sheeran promises.

Sheeran has zero traces of impostor syndrome. He looks at the dozens of songs he’s discarded for every hit, the hundreds of shows he played before anyone knew his name, and is sure he knows how it all happened. But, he says, “people do look at me and they’re like, ‘How did you get in that position?’ ”

Again, he gets it. “I am a nerd,” he says. “I love Lord of the Rings. I love Pokemon. I love fucking Lego and Warhammer, and yeah, I’m not meant to be considered cool.” But he’s long since ascended to an elite level of geekery. When he was very young, he admits, he saw Pikachu et al. as his “friends”; now he’s the guy who gets asked to write a song (the Coldplay-ish anthem “Celestial”) for a new Pokemon game. He once assembled both a Lego Death Star and a Millennium Falcon with a 1D-era Harry Styles, cameoed in 2019’s The Rise of Skywalker, and has been pals with Lord of the Rings auteur Peter Jackson since writing a song for 2013’s The Hobbit: The Desolation of Smaug. The other week, in Wellington, he watched North by Northwest in Jackson’s home screening room, with fellow New Zealand resident James Cameron and family also in attendance.

With Sheeran’s new album, – (pronounced Subtract), due May 5, he’s in sudden danger of achieving a new brand of musical coolness, thanks to some of his most unadorned and emotive songwriting, paired with the chiaroscuro inventiveness of production by the National’s Aaron Dessner. Sheeran knows there’s a chance critics might actually like this one, which kind of scares him: “I’m worried about that, because all my biggest records, they hate.”

He’s sitting cross-legged and shoeless on the gray cushion of an outdoor couch, wearing a crisp white T-shirt, black shorts from the Italian brand Stone Island, and white tube socks. His arms are a rainbow riot of tattoos, quotes in Gaelic and Dwarvish among them. He’s got a scruffy, reddish beard going, and his longish hair sticks out of a baseball cap from Lowden Guitars, a high-end acoustic-guitar manufacturer. When he was a kid, he dreamed of playing one; now he’s a collaborator on a signature model.

Sheeran’s hero and friend Eric Clapton got him into serious watch collecting, as he did for John Mayer, and today’s wristwear is a Patek Philippe Perpetual Calendar model that seems to be worth at least six figures. (Don’t bother trying to get his take on Clapton’s anti-vax turn, by the way: “I love Eric. I don’t want to say anything bad about him,” says Sheeran, who started playing guitar after seeing a “Layla” performance on TV. He is, himself, vaccinated, but has managed to contract Covid at least seven times, thanks to constant travel and the kids.)

In keeping with the album’s themes, Sheeran has “super-heavy” stuff — death, illness, grief, depression, addiction — to talk about this week, in the most extensive interviews he’s done in at least five years. He’ll end up revealing it all, maybe more than he planned, but he’s wary of the world’s reactions. First of all, he imagines people seeing it through the highly unsympathetic lens of “Rich Pop Star Feels Sad.” And then there’s the fact of the particular pop star he is. In his mind, he admits, “there is a lot of, like, ‘Why do people care whether I feel this way or that way?’ ”

Sheeran encounters hostility almost exclusively online these days, when it reaches him at all. But when he first started coming into London as a teenager, toting his acoustic guitar and loop pedal from gig to gig, trying to get signed, he’d hear it right to his face. “I spent so long with people laughing about me making music,” he says. “Everyone saw me as a joke, and no one thought I could do it.” The way he sees it, he alchemized all that contempt and doubt into artistic fuel. “And I think that’s still the drive. There’s still this need to prove myself. And I’m still kind of not taken seriously. If you were to speak to any sort of muso, ‘Oh, I love my left-of-center music,’ I’m the punchline to what bad pop music is.”

At some point long ago, he decided not to worry about it. “I mean, mate, when I wrote ‘Perfect’ and ‘Thinking Out Loud,’ I remember being like, ‘Oh, these are a bit cheesy,’ ” he says. “But at the time being like, ‘I don’t know if I care.’ And they became the biggest ballads in the world that year. And you’re like, ‘Well, people must connect with cheese, then!’ ” Sheeran isn’t afraid to say what he means in his songs, at nearly all times. If he’s grown up and is a father now, he sings, “I have grown up/I am a father now” — the opening line of 2021’s =. His use of metaphor is sparing. He loves Van Morrison, but if Sheeran wrote a song called “Listen to the Lion,” it would probably be about a trip to the zoo, and a Top Five worldwide hit to boot.

Someone on Twitter recently accused Sheeran of making “sex anthems for boring people,” a critique he needs only a millisecond to contemplate. “150 million boring people, by the way,” he shoots back, referring, loosely, to his total album sales, a figure that clearly hovers close to the surface of his mind. “I think I’m quite meme-able. Have you seen the meme of me when I’m queuing up at a record store in my own T-shirt with a bag that says “÷” on it? And it says, ‘Why does Ed Sheeran look like he’s queuing up to meet Ed Sheeran?’ I think it’s because I am quite quote-unquote ‘ordinary-looking.’ I look like someone’s older brother’s mate that has come back from college and works in a pizza shop.”

In truth, at this moment, with his 32nd birthday about to hit, he looks less ordinary than ever. The beard lends him a certain glamour, and he’s lean enough these days to expose sharp cheekbones he credits to an hour of weightlifting a day, pointing to a set of dumbbells on the porch. There’s a river’s worth of feeling in his deep-blue eyes, recently lasered out of nearsightedness, a striking contrast to all that red fuzz. “Babies love Ed, because he’s got an unusual face,” says Seaborn. She exudes warmth, intelligence, and ponytailed sportiness, and also happens to be the subject of a worshipful song — “Shape of You” — that’s been streamed billions of times. (She’ll tell some of her story in May 3’s documentary series, Ed Sheeran: The Sum of It All, streaming on Disney+.)

For what it’s worth, and it’s worth a lot, Sheeran’s friend and collaborator Taylor Swift thinks Sheeran is thoroughly great, “the James Taylor to my Carole King,” as she told Rolling Stone a few years back. She hooked him up with Dessner, her Folklore and Evermore partner, to work on the Swift-Sheeran co-write “Run,” for her Taylor’s Version remake of Red, before suggesting they work on Sheeran’s music. Dessner finds it “boring” to contemplate the idea that Sheeran or his music might be uncool. “He’s a brilliant writer,” he says. “I’ve seen it up close.”

Sheeran wouldn’t mind making new fans with Subtract, but he doesn’t need your grudging acceptance. “Someone who’s never liked my music ever? And sees me as the punchline to a joke? For him to suddenly be like, ‘Oh, you’re not as shit as I thought you were?’ That doesn’t mean anything.”

Sheeran is crying again, and he’s glad. It’s nearly been a year, and he doesn’t want the pain to fade quite yet. “I don’t want to get over it,” he says. “I would hate to talk about it, but not feel …” His eyes and his face are equally red now, and he can’t quite get the words out.

On Feb. 20 of last year, Jamal Edwards, one of the U.K.’s most prominent young music entrepreneurs, died suddenly at age 31, of a cardiac arrhythmia brought on by cocaine use. He was Sheeran’s best friend, and the artist believes he owes Edwards his career, thanks to cred-establishing appearances on his influential YouTube channel SBTV when he was struggling for industry attention. Edwards’ final Instagram post was a tribute to his old friend. “Happy Birthday to the OG, Ed. Blessed to have you in my life brother. You know you’ve been mates a long time when you lose count on the years! Keep smashing it & inspiring us all G!”

The two friends had an easy chemistry that you can hear in an old YouTube clip where Sheeran trades lines from the grime track “Burst Da Pipe” with Edwards, who’s holding the camera, both of them cracking up. “People assumed that we were lovers,” Sheeran rapped on a recent tribute to his friend, “F64.” “But we’re brothers in arms.” “That was a big rumor in the industry,” Sheeran says. “And I don’t think anyone thought that I knew the rumor. But I get it, man. I lived in his room!”

When he was 18 and had no place to live in London, he crashed for the night at Edwards’ house, and ended up staying for “God knows how long. Like, I get why people would think that. We used to go on holidays together.” The night before he learned of Edwards’ death, Sheeran was out to dinner with Swift and Joe Alwyn, exchanging texts with Edwards about plans to shoot a video the next day. “Twelve hours later,” Sheeran says, “he was dead.”

February of last year was already the worst month of Sheeran’s life. Just before Edwards’ death, Seaborn, six months pregnant, was diagnosed with a tumor that needed surgery — which couldn’t happen until after she gave birth. There was talk of delivering early, though she ultimately carried Jupiter to term and had successful surgery in June, the morning of a Wembley concert for Sheeran. “There’s nothing you can do about it,” he says. “You feel so powerless.” Meanwhile, he was in court defending a plagiarism lawsuit over “Shape of You,” “being called a thief and a liar.” (He won the suit.)

Edwards’ death shattered him, sent him spiraling. “My best friend died,” he says, tearing up for the first time in our discussions. “And he shouldn’t have done.” He found himself in his latest bout of what he quietly knew to be depression. “I’ve always had real lows in my life,” he says. “But it wasn’t really till last year that I actually addressed it.”

He first experienced it in elementary school, a period that’s sometimes played for laughs in chronicles of his life, but turns out to have been deeply traumatizing. “I went to a really, really sport-orientated primary school,” he says. “I had bright red hair, big blue glasses, a stutter. I couldn’t play the sport because I had a perforated eardrum. You’re just singled out for being different at that point. I’ve kind of blocked out a lot of it, but I have a real hang up about that. I think it plays into wanting to be on a stage and have people like you and stuff.”

In the wake of Edwards’ death — and then, on top of everything else, the passing of another friend, Australian cricket star Shane Warne, in early March — Sheeran started experiencing a feeling he’d silently suffered through before. “I felt like I didn’t want to live anymore,” he says, his voice steady. “And I have had that throughout my life.… You’re under the waves drowning. You’re just sort of in this thing. And you can’t get out of it.” Those thoughts were bad enough, but shame arrived as their companion. They seemed “selfish,” he says, “especially as a father. I feel really embarrassed about it.”

It was Seaborn who figured out what was going on, and told Sheeran he needed help. For the first time in his life, he started seeing a therapist. “No one really talks about their feelings where I come from,” he says. “People think it’s weird getting a therapist in England.… I think it’s very helpful to be able to speak with someone and just vent and not feel guilty about venting. Obviously, like, I’ve lived a very privileged life. So my friends would always look at me like, ‘Oh, it’s not that bad.’ ”

Therapy has been deeply helpful, but not magical. “The help isn’t a button that is pressed, where you’re automatically OK,” he says. “It is something that will always be there and just has to be managed.”

As he talks, Sheeran keeps pulling at a loose silver chain on his right wrist. He spent most of last year wearing two rubber bracelets. One was from Edwards’ funeral, the other, bearing the slogan “Don’t fuck up,” from yet another lost friend, the Australian music exec Michael Gudinski, who died in 2021. On Christmas, Seaborn gave Sheeran the new jewelry, with Jupiter’s and Lyra’s names engraved inside. On New Year’s Day, Sheeran made the switch. “It felt symbolic,” he says, “to take off those bracelets and put on one for my family.”

Sheeran’s other form of therapy was his usual one: writing songs. Since 2011, Sheeran has been executing his plan for a cycle of albums with titles based on mathematical symbols, and Subtract, now the last of those five releases, was always in the mix. The idea was a stripped-down singer-songwriter album, returning him to his earliest roots, and he’d spent more than a decade on it, “sculpting this perfect thing.” By early last year, it was ready to go. But the version of Subtract he’s putting out in May isn’t that album at all.

In late 2021, Swift’s matchmaking led to Sheeran and Dessner sitting down for a sushi dinner in New York. Dessner recalls telling Sheeran that he “would love to hear him in a more vulnerable, more sort of elemental way.” Not long after that conversation, Dessner did his thing, sending Sheeran fully arranged instrumental beds that just needed vocal melodies and lyrics.

In the midst of Sheeran’s month from hell, he started writing over the tracks. “I wasn’t really around a guitar,” he says. “But I had these instrumentals, and I would write to them — in the backs of cars or planes or whatever. And then it got done. And that was the record. It was all very, very, very fast.”

Sheeran, like much of humankind, is a huge fan of Swift’s Dessner-produced Folklore and Evermore. While he was determined not to copy them, he does think Dessner helped him and Swift tap into the same mode of free, fast-flowing writing. Usually, Sheeran sits in a room with collaborators, bouncing ideas back and forth. In contrast, Dessner delivers a finished musical landscape. “And then he goes, ‘Now you say what you want to say,’ ” Sheeran says. “So there’s no filter. There wasn’t any going back and checking on any lyrics. And I think that’s what was brilliant about Folklore and Evermore — it’s just complete brain-to-page. That’s where you get lines like ‘When I felt like I was an old cardigan under someone’s bed, you put me on and said I was your favorite.’ There wasn’t anyone challenging that line. And that’s why it’s brilliant.”

The opening track, “Boat,” evokes one of Sheeran’s early heroes, the singer-songwriter Damien Rice, in its starkness, with Dessner’s textured chords swelling beneath acoustic strumming. (Sheeran wrote it over a piano-and-drums bed created by Dessner, but reworked it as a raw guitar song.) “They say that all scars heal, but I know maybe I won’t,” Sheeran sings, sounding more plaintive than you’ve ever heard him. “The waves won’t break my boat.” On another ballad, “Life Goes On,” Sheeran sings directly of Edwards: “Life goes on with you gone, I suppose/I sink like a stone.”

The lovely midtempo track “Dusty,” propelled by ticking synthetic hi-hats, is lighter, capturing an epiphany Sheeran had during a morning ritual of listening to vinyl with Lyra — in this case, Dusty Springfield’s Dusty in Memphis. “I’m going through that time of turbulence and massive lows,” Sheeran says, “but then waking up in the morning and having a joyous morning with a beautiful girl. It’s such a weird juxtaposition to go to bed crying and wake up smiling with your daughter.”

“Eyes Closed,” the first single, is built around a pinging pizzicato riff that builds to an octave-jumping chorus as big as anything in Sheeran’s catalog: “I’m dancing with my eyes closed/’Cause everywhere I look I still see you.” It’s a rewrite of a more straightforward pop song Sheeran had on hand, a more generic breakup narrative. Now it speaks directly to his traumas and their aftermath: “I pictured this month a little bit different/No one is ever ready.”

There are 14 tracks on –, but that’s not the end of Sheeran and Dessner’s collaboration. Sheeran yanked three tracks from the album that felt too joyous, and realized they were the start of something else. “It was very quickly seen that we were making two different things,” says Sheeran. He went on to write an entirely separate second album with Dessner. He’s already mixing that one, though he’s not sure when it will come out; he wants to give – a chance to breathe. “I have no goals for the record,” he says. “I just want to put it out.”

Sheeran has five more albums in mind using another category of symbols, one he’s not ready to share, at least on the record. He sees the last in that series as a years-long project, with a twist. “I want to slowly make this album that is quote-unquote ‘perfect’ for the rest of my life, adding songs here and there,” he says. “And just have it in my will that after I die, it comes out.”

This what Ed Sheeran does before he goes onstage in front of 50,000 people: practically nothing. He switches from his usual T-shirt and shorts and watch and sneakers into a modestly sharper stage outfit, and heads out, without so much as a final glance in the mirror or a comb through his hair. No vocal warmup, even. He wakes up on show days feeling no different than on any other days, and talks to the vast crowds the same way he speaks offstage. His persona is no persona. (As for the infamous photo of a glammed-up Beyoncé duetting with a dressed-down Ed: “I think it symbolizes two people being themselves, personally. She is the best performer on Earth. And I am a bloke in a T-shirt.”)

At 5 p.m. the day after our first meeting, just three hours before showtime at Auckland’s Eden Park stadium, Sheeran is back at the house, with the kids eating dinner at a circular table. “Me and Cherry were talking earlier about how it’s so lovely,” Sheeran says. “We had an entire day. We did nothing but this. It’s so nice and wholesome having family on tour. On the last tour, I’d party till 7 a.m., sleep till 4 p.m., get up and do the gig. But I was like, 26. It’s very different.”

The SUV ride to tonight’s venue is only 20 minutes, during which we pass dozens of Sheeran’s fans making the same journey on foot. We happen to hear “Love Yourself,” the smash he gave to Justin Bieber, on the radio — the recording, he notes, is just his version with Bieber’s voice replacing his own. We pass several barricades and are whisked inside. Sheeran’s dressing room is a big, airy refuge, set off by white curtains, with a cream-colored couch at its center, and an elaborate play area in one corner, just in case the kids show up. A foil-covered dinner of Japanese noodles and vegetables arrives for Sheeran, and as with every meal he eats in our time together, he’s arranged for me to be served the same — not a move that would occur to most celebrities.

There’s a wireless sound system in a road case in the corner, and Sheeran uses some idle time before his show to play me some unreleased music. Like, a dizzying, unbelievable amount of unreleased music, in so many styles it almost feels like a prank. “I’ve got loads and loads and loads of shit,” he says. Instead of waiting for inspiration, his method is to just keep the faucet flowing. “I wrote 25 songs the week I wrote ‘Shape of You,’ ” he says. But he’s never had so much finished music piled up that he’s this excited about. It’s years’ worth of releases, in his estimation. “Who’s to say at what point creativity stops,” he says, “and you can’t write any more songs? At least there’s enough banked up.”

He starts out by playing an airy ballad, “Magical,” from his second album with Dessner. “This is how it feels to be in love,” he sings. “This is magical.” Another Dessner song, a likely single, has a bright “Solsbury Hill” feel: “Saturday night is giving me a reason to rely on a strobe light,” he sings, amid more meditations on grief. A third Dessner production is a surging Bruce Springsteen-inspired track called “England.”

There is, as it turns out, yet another completed album waiting in the wings, a collaboration with reggaeton superstar J Balvin. They knocked the whole thing out last year, after Sheeran randomly encountered Balvin (José, he calls him) in a hotel gym a couple of years earlier. The album is all ready to go, complete with already-shot videos, but again, with no release date in sight. He plays a track that bridges Afropop and reggaeton, joined by Burna Boy and Balvin. Another Balvin-produced track is a collaboration with Daddy Yankee, with Sheeran singing a hook between rapped verses; yet another is a slower reggaeton song where Sheeran actually raps in Spanish. “I wrote it in English,” he says, “and they translated it in the studio.” There are collaborations with Pharrell Williams and Shakira as well — turns out Sheeran has been writing for her next album, too.

Sheeran plays a grime track where he full-on speed-raps, trading off with the British rapper Devlin, another friend of Edwards. “Like Kendrick Lamar, this shit ain’t free,” Sheeran raps. There’s a drum-and-bass banger “for the ravers” that he wants to release as a double A side with a David Guetta-produced track where Sheeran praises “summer vibration.” Another Guetta song is even more shameless in its Vegas-EDM feel, but it’s not for Sheeran — they’re trying to figure out who’ll sing it.

There’s a striking doo-wop-meets-Paul McCartney song called “Amazing Daughter,” the first thing Sheeran wrote after he briefly persuaded himself he should retire from music to become a stay-at-home after Lyra’s birth. It’s an outtake from his last album that he loves, but has no idea where he’ll find a place for it.

He plays a remnant from time spent in Nashville, a nearly parodic bro-country song he wrote with Florida Georgia Line that Sheeran assumes they rejected as too-on-the-nose: “My neck’s still red, the sky’s still blue, my truck’s still big, my girl’s still you … we live where we live because we love living in Middle America.”

Then there’s a collaboration with Benny Blanco, and, oh, yeah, a lighters-up power ballad duet between Sheeran and Bieber, which Sheeran worked on with superproducer Andrew Watt, slated for Bieber’s next album.

On top of it all, there’s the big-ass song Sheeran wrote for the series finale of Ted Lasso, airing in the spring. “Do you want to hear it?” he asks. “Because it’s fucking good.” “We’ll rise from the ashes and write in stars with our names,” he sings in a chorus Chris Martin will envy, complete with whoa-whoa-whoas.

“Sorry,” Sheeran says at the end, unnecessarily. “I know I’ve just, like, song-vomited on you.”

Snow Patrol guitarist Johnny McDaid, one of Sheeran’s most frequent collaborators, has long since gotten used to Sheeran’s genre hopping. “A songwriter is sort of an antenna,” he says. “They pick things up in the ether, and depending on how wide the frequency band of your antenna is, you tend to genre-fy yourself. With Ed, his frequency band is so wide that it really can come from anywhere and be anything.”

It’s nearly showtime, and Sheeran strips from today’s outfit (nearly the same as yesterday’s, with the exception of rare Marty McFly-model Nikes) to his black boxer briefs, and pops on his stage clothes. He has a secret method of transport through the crowd that he asks me not to reveal. Once that mystery journey is over, we’re underneath his yacht-size rotating stage, currently covered by a sort of metal cage that will rise to reveal Sheeran after a countdown on the video screens. There’s about three minutes left, and Sheeran is still uncannily calm, promising a sound guy (known as Normal Dave, in contrast to another Dave in his employ) a celebratory drink soon. As the countdown hits 90 seconds, Sheeran insists that I scamper up to the stage itself, to the spot by his mic stand, and take it in. The vast crowd is visible through the enclosure, all around you. You’re facing them alone, with just your loop pedal and guitar. There doesn’t seem to be much to be calm about.

“Forty seconds!” a stage manager warns, and I vacate the stage, with Sheeran taking over. The concert proceeds as planned, with singalongs and phones held aloft during the slow songs and Sheeran explaining how his loop pedal works, as he has every night for years. (These days, a full band, kept to side stages, does join him for a few songs.) Then he gets to “Bloodstream,” a moody 2014 confessional about an MDMA experience. The stadium glows blood-red as he builds the loop that drives the song — a bassy thump on the guitar, a driving arpeggio. But three minutes in, a rising tide of static overtakes the music. Sheeran stops and disappears under the stage. He reemerges and starts again. A minute in, the static returns. He repeats the process. More static, another disappearance. Sheeran’s production team is starting to sweat.

Finally, Sheeran informs the crowd that the noise is coming from his loop pedal, which won’t be working for the rest of the concert. He finishes the show by playing seven songs, several of them not on the set list, all just voice and guitar, unadorned. He’s forced to rework his hits in strummy coffeehouse arrangements, rendering the pyro effects during “Bad Habits” slightly comical. The fireworks bursting from the stage at the very end of the concert are so incongruous that Sheeran can’t help laughing.

For the crowd, the whole thing is a revelation, and you’ll hear people in Auckland talking about it on the street for days afterward. How many other artists of Sheeran’s or younger generations could pull this off?

Backstage, Sheeran is in a mild state of shock. “Yeah, fuck me,” he says, sighing. He can’t bring himself to perceive the evening as the triumph it is; all he sees is a crowd that didn’t get its money’s worth.

He makes it clear his team needs to fix the problem, but there’s never a question of a tantrum, onstage or off. “What can you gain shouting at people?” he asks. “I also think people work harder for you. If someone’s shouting, you’re just like, ‘Fuck you.’ ”

We were supposed to do another interview tonight, but Sheeran bumps it until tomorrow, a decision he says he made onstage. Instead, he eats a steak (again, I get one too), and starts seriously drinking red wine. Some of the old schoolmates who now work for him fill the room, and pour themselves glasses. The lights dim, and any remaining tension eases. “Let’s just forget tonight,” Sheeran says, raising a glass. “Let’s just forget it ever happened.”

But he doesn’t forget. And he doesn’t get much sleep, either. One of his kids has tonsillitis, so he’s up most of the night, and when he wakes up, his first thought is of the previous night’s troubles. “It was a good outcome,” he acknowledges, “but it’s just not what people paid for. It’d be like going to watch Avatar, and it stops halfway through. Then James Cameron comes out at the end and just narrates it. You’d be like, ‘Oh, that’s a new experience!’ But it’s not what you paid for.”

When we meet again in the same backstage area the next day, he’s got on the same shorts and a pastel hoodie, and his energy is a little edgier than usual. His crew spent long hours pinpointing the source of that show-stopping static: Turns out subwoofer vibrations damaged a chip in the loop pedal’s digital brain, and they’re ordering backups.

We sit on the dressing-room couch and start talking about “Bad Habits,” his 2021 smash. He’s mentioned in the past that the song is about “addiction issues,” but it never seems to register with anyone. “If you sing that on a piano really slowly,” he says, “it’s like a confessional song about addiction.”

Earlier, he told me he “used to be a party boy in my twenties.” But it went further than that. “I was always a drinker,” he says. “I didn’t touch any sort of like, drug, until I was 24.” But beyond weed, he did get into a “few” substances, which he won’t name, because he doesn’t want his kids reading it someday.

He’s vague on how and when he broke from those substances, but makes it clear the hardest thing was quitting hard liquor. “Two months before Lyra was born, Cherry said, ‘If my waters break, do you really want someone else to drive me to the hospital?” he recalls. “Because I was just drinking a lot. And that’s when it clicked. I was like, ‘No, actually, I really don’t.’ And I don’t ever want to be pissed holding my kid. Ever, ever. Having a couple of beers is one thing. But having a bottle of vodka is another thing. It’s just a realization of, ‘I’m getting into my thirties. Grow up! You’ve partied, you’ve had this experience. Be happy with that and just be done.’ I love red wine, and I love beer. I don’t know any old rockers that aren’t alcoholics or sober, and I didn’t want to be either.”

Edwards’ cocaine-related death only cemented his feelings about certain substances. “I would never, ever, ever touch anything again, because that’s how Jamal died. And that’s just disrespectful to his memory to even, like, go near.”

Quitting hard liquor helped him moderate his food intake, and his newish exercise habit has changed his body. But food, too, has been a struggle. “I’m self-conscious anyway, but you get into an industry where you’re getting compared to every other pop star,” he says. “I was in the One Direction wave, and I’m like, ‘Well, why don’t I have a six pack?’ And I was like, ‘Oh, because you love kebabs and drink beer.’ Then you do songs with Justin Bieber and Shawn Mendes. All these people have fantastic figures. And I was always like, ‘Well, why am I so … fat?’ ”

He chuckles, with zero humor. “So I found myself doing what Elton [John] talks about in his book — gorging, and then it would come up again.” (Elton John put it this way: “I had developed bulimia.”) “There’s certain things that, as a man talking about them, I feel mad uncomfortable. I know people are going to see it a type of way, but it’s good to be honest about them. Because so many people do the same thing and hide it as well.”

Again, all of these battles are continuous. “I have a real eating problem,” he says. “I’m a real binge eater. I’m a binge-everything. But I’m now more of a binge exerciser, and a binge dad. And work, obviously.”

It’s almost showtime again, but Sheeran is happy to keep talking, with one half-joking request: “If I don’t cry in the next 40 minutes, that would be great.” This time, the show is flawless, and the hit singles at the end go off in their full, loop-pedal glory, the climactic fireworks fully earned. He makes a point of expressing his gratitude for his crew from the stage.

“Fuck me,” he says backstage afterward, in an entirely different tone, a white towel around his neck. “Perfect show! That was so good. We should fuck up more often.” He’s thrilled, and so ready to celebrate that you’d almost think it was his first big concert.

Sheeran is “very grateful to do what he does,” says McDaid, his songwriting partner. “A lot of people in his position aren’t. He walks into a room to write a song, and tells me how grateful he is to be doing this.”Lately, he’s found more elemental reasons to be thankful. Earlier in the week, he and Seaborn made the two-hour trip from Auckland to rural Waikato, where Hobbiton — the Shire sets built for Lord of the Rings — still stands, among the impossible verdant beauty of New Zealand’s grasslands. A year after everything blew apart, the couple sat on a bench, sipped red wine, and watched the sun dip down, talking about their kids and their good fortune. “We’re so grateful,” Sheeran says, “to be alive.”