Bowie’s Berlin: the locations behind the lyrics

We follow the Thin White Duke’s lyrics through the German capital he once called home, discovering a world of bright lights, late nights, intrigue, politics and music

My flight eases me into Brandenburg Airport. I have spent the two hours in the air listening to the three albums that make up Bowie’s Berlin Trilogy: Low, Heroes and Lodger, most of which was written in what was then a capitalist island floating in a Soviet sea. This is an airport which Bowie — who would have been 75 on 8 January — would not have known when he moved to Berlin from Los Angeles, skeletal and shattered, in 1976. The East and West airports have only recently closed, their much-delayed successor finally sealing reunification more than 30 years after The Wall fell, an event in which, arguably, Bowie had a large part to play.

Bowie and Berlin were well matched. He absorbed and reflected its darkness and angularity and, in turn, it rehabilitated his creative drive and artistic hunger.

Whether you are here for a few days or “starting a new career in a new town”, as Bowie sang, you can immerse yourself in the musicality and culture which attracted this ‘London boy’ to Berlin and inspired the artists who followed in his wake.

“I stumble into town, just like a sacred cow / visions of swastikas in my head, plans for everyone”

– ‘China Girl’, Let’s Dance, 1983

“Berlin was a strange, singular place,” Bowie once recalled. It still is. Winter suits the spirit of this city: moody, oppressive, yet enticing. I watch the snow settling on the landmark Oberbaum Bridge from the tenth floor of Berlin’s music-themed hotel, the nhow. This high-end establishment, which lends guitars as part of its room service, makes the most of Berlin’s historic relationship with music. As well as lift music that spans different genres, it’s even home to an in-house recording studio which is often utilised by Universal Music next door.

Bowie arrived in Berlin in his Mercedes-Benz, drawn to the city by its offer of isolation and anonymity. To this day, Berliners aren’t easily impressed, and being Aladdin Sane wasn’t going to cut it in a town of oddballs. The city was geopolitically unique: West Germans were able to escape conscription here, and as closing times had been abolished by occupying forces in 1949, the clubs and bars had no curfew (still the case now, Covid-permitting). It was a perfect recipe for outcasts and squatters.

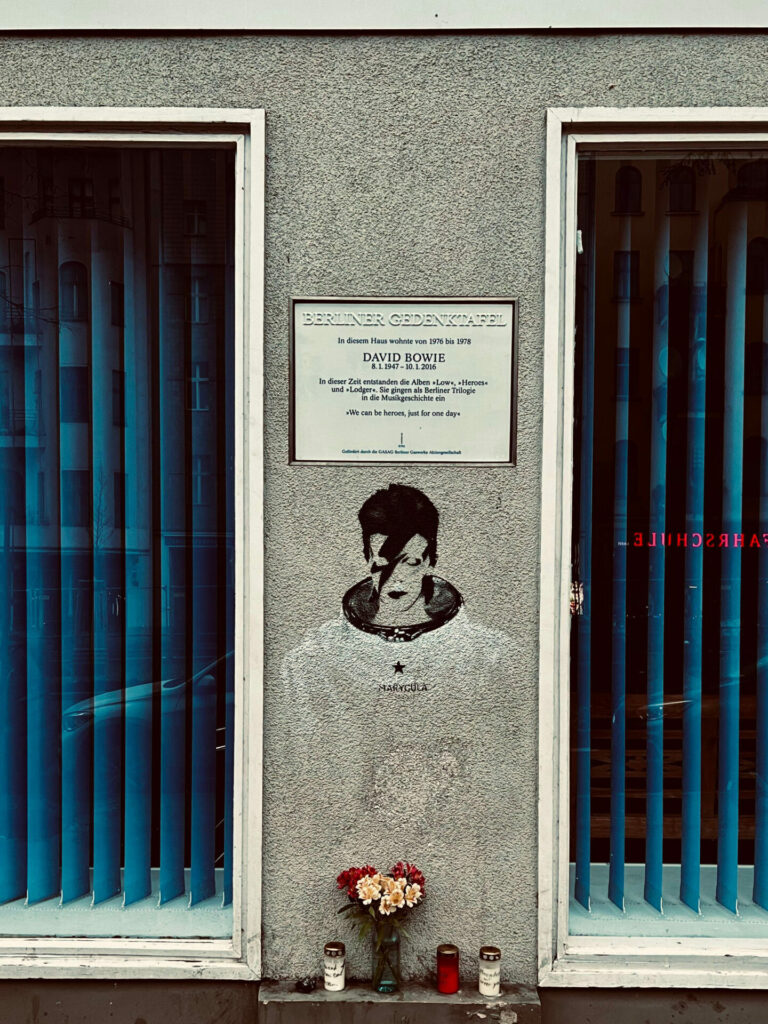

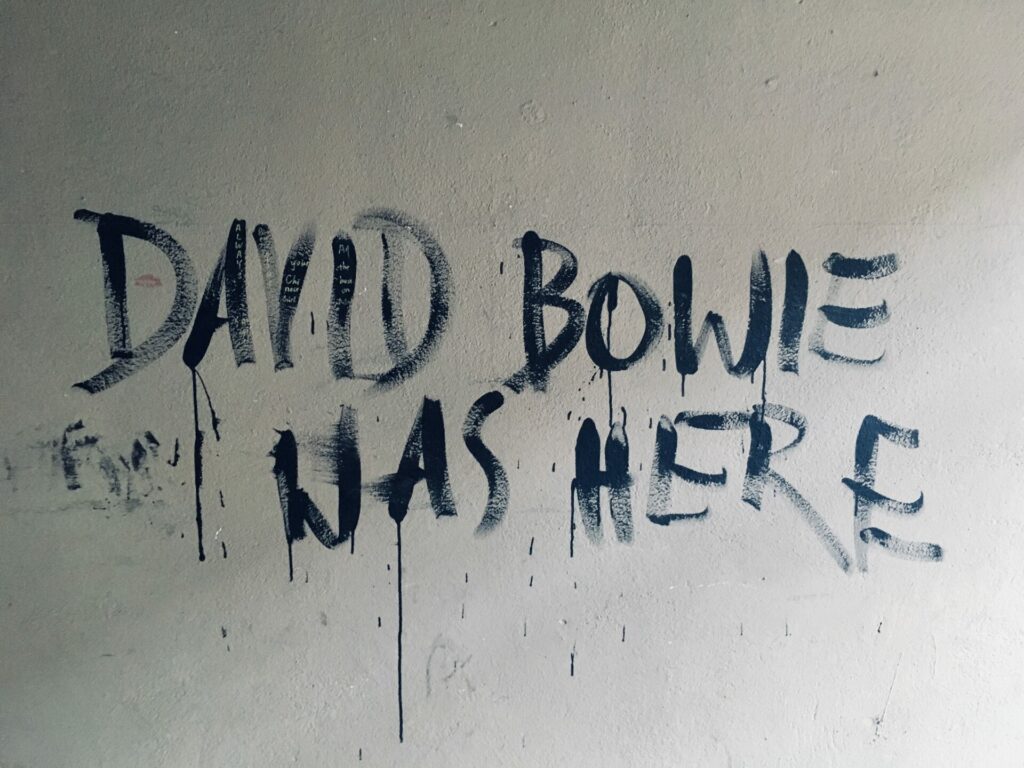

Bowie brought Iggy Pop with him and helped get his friend’s career back on form. Iggy’s first Berlin LP, The Idiot, contains ‘China Girl’ — later translated into a super-hit by Bowie and Nile Rodgers — and opener ‘Sister Midnight’, which was reinterpreted as ‘Red Money’, the final track of Bowie’s Berlin Trilogy. For a while, they were flatmates in Bowie’s spacious apartment at Hauptstrasse 155 in the anonymous Schöneberg district, which fans still visit in silent reverence following Bowie’s death in January 2016.

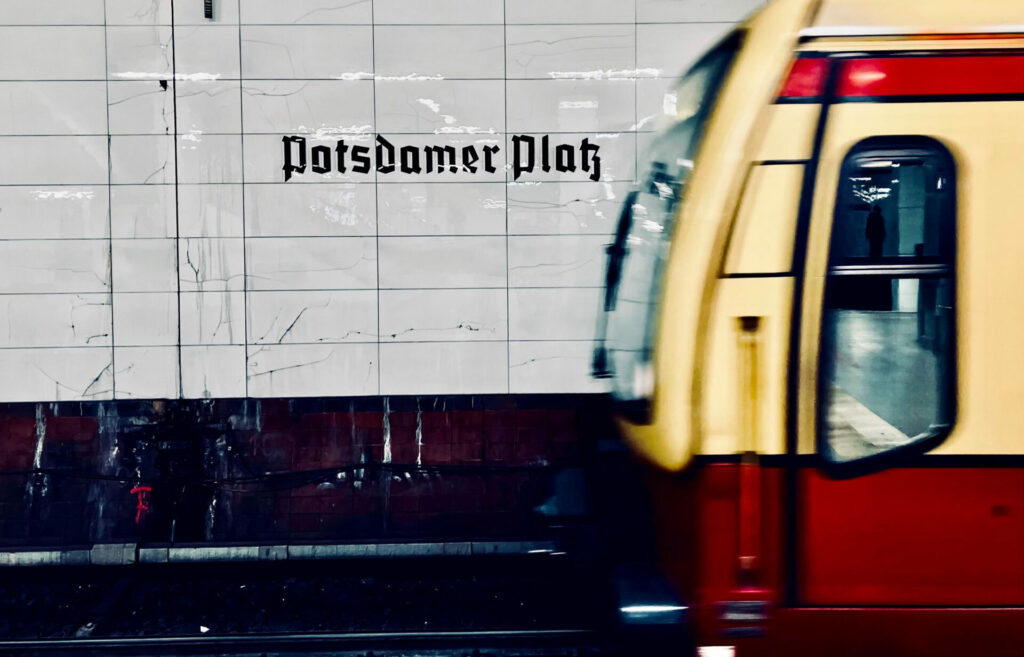

“Had to get the train / from Potsdamer Platz”

– ‘Where Are We Now?’, The Next Day, 2013

Potsdamer Platz, now one of Berlin’s major railway interchanges, once sat on the Death Strip, the lethal piece of land sandwiched between two insurmountable walls separating East and West Berlin. Overlooked by East German border guards, it was festooned with trip wires, floodlights and landmines to deter escapees from the East. As Westerners, however, particularly with Allied passports, Bowie and Iggy were able to take day trips into East Berlin, passing through the infamous Checkpoint Charlie or by train through the Palace of Tears.

Once in the Mitte district, they were regular attendees at Brecht’s Berliner Ensemble theatre and would then go next door to the exclusive Ganymed restaurant, where political deals were done between the bureaucratic bigwigs of the German Democratic Republic (GDR), and where Bowie’s Western currency would buy him a filet mignon for a dollar. Now a sophisticated French brasserie, the duck option costs slightly more, but the walls teem with history. They’ve removed all the listening devices now (hopefully), and the management are happy to regale you with a few tales.

When I visit the Stasi Museum in the Lichtenberg district, I am told that, although Bowie’s music was frowned upon as ‘antisocial’— his music and imagery seeping into the Eastern Bloc, promoting individuality and representing ‘Western decadence’ — there was no file on him. This is surprising given the cultural threat he posed, and how the ultra-paranoid East German Secret Police’s (Stasi) archives contain 69 miles of files in total… At one point there was one Stasi informant for every 6.5 citizens.

“I can remember / standing by the wall / and the guards shot above our heads / and we kissed as though nothing could fall”

– ‘Heroes’, Heroes, 1977

Look at the artwork for Iggy Pop’s The Idiot and Bowie’s Heroes and you will notice both men striking awkward, jagged poses. These were a tribute to Bowie’s obsession with German Expressionism, particularly the Die Brücke group of artists.

Sitting on the outskirts of the city, the Brücke-Museum is nestled among trees and lakes. “The Heroes cover is heavily influenced by the painting Roquairol by Erich Heckel, which David Bowie saw at the Brücke-Museum,” curator Lisa Marei Schmidt tells me. The artwork’s sense of alienation and subversion of form spoke to Bowie’s artistic sensibilities.

But it is a work painted by fellow Die Brücke member Otto Mueller on the Western Front in the First World War which dispels a rock ’n’ roll myth. In the eponymous song from the album, Bowie makes a rare direct reference to Berlin. The story goes that, lost for lyrical ideas, Bowie was gazing out of the studio window when he witnessed his producer, Tony Visconti, kissing ‘Heroes’ backing singer, Antonia Maass. The most likely influence, however, is Pair of Lovers Between Garden Walls, one of Bowie’s favourite Brücke group paintings. The strong imagery of this piece stayed with him, and he peppered this with his own contemporary observations — armed GDR border guards with a direct view from their watchtower into Hansa Studios, where Bowie was recording. It became the song’s most seminal moment.

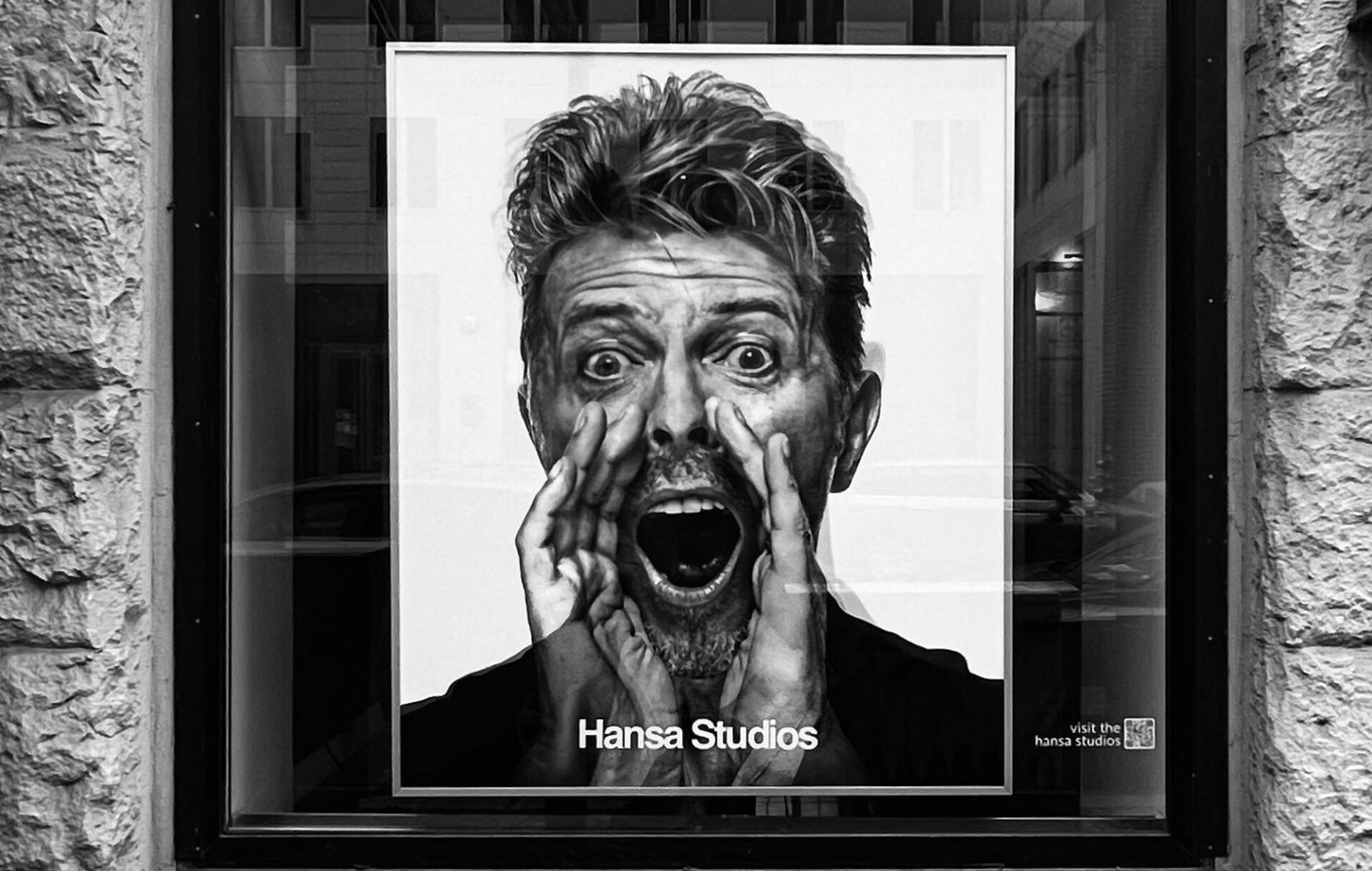

Back in central Berlin, you could almost walk straight past Hansa Studios, were it not for an eye-catching hologram of an older Bowie in one of the front windows. A sign advises against popping in to ask for a tour, directing fans instead to Berlin Music Tours, where Thilo Schmied arranges visits to the working studios, as well as Bowie Bus Tours and Bowie Berlin Walks.

“Sitting in the Dschungel / on Nürnberger Strasse”

– ‘Where Are We Now?’, The Next Day, 2013

The Dschungel — or Jungle — was the nightspot during Bowie’s time in the city. It was Berlin’s version of New York’s famous Studio 54. As it’s long since closed (though there is a bar of the same name in Kreuzberg), from its old site on Nürnberger Strasse, head north to a different kind of jungle.

The quirky yet luxurious 25hours Hotel Bikini Berlin overlooks the monkey enclosure of the world-famous Zoologischer Garten Berlin, and sits next to the train station of the same name, known locally as Bahnhof Zoo. Christiane F. — Wir Kinder vom Bahnhof Zoo is also the title of a bleak, gritty, 1981 film for which Bowie provided the soundtrack, largely made up of his Berlin Trilogy music. A short walk from here is KaDeWe, a chic department store, where Bowie did his grocery shopping in what is, basically, Germany’s version of Harrods Food Hall. There are cheaper places to procure a litre of milk.

“One more weekend / of lights and evening faces”

– ‘DJ’, Lodger, 1979

Strangely, Bowie moved to Berlin to escape the drug culture of LA, but it’s difficult to behave like a saint in this city. Apart from the Dschungel, his regular evening haunts included punk club SO36, gay club Neues Ufer and numerous drag and cabaret clubs (KitKatClub — inspired by the club of the same name from the musical Cabaret — is the best modern-day iteration of this). He also hung out at Paris Bar, Charlottenburg, where he gave interviews to journalists, including an infamous one with Rolling Stone, when he ended up so drunk that he crawled out of the bar. It still does an amazing steak frites, his favourite, and the alcohol selection remains comfortingly overwhelming.

The Thin White Duke vacated his apartment in 1978 and the majority of Lodger was recorded in Montreux and mixed in New York, where he settled permanently. Bowie never forgot his time in the German capital, however, as demonstrated with the reference-heavy ‘Where Are We Now?’, the lead single from The Next Day, his penultimate studio album.

It was on a return visit eight years after Bowie left Berlin that saw him make his most profound mark on the city. In 1987, as thousands of Westerners flocked to see his Glass Spider tour in front of the then derelict Reichstag, a quarter of the speakers were turned towards East Berlin.

Sporting a coiffed mullet and draped in a scarlet suit, Bowie proclaimed, “The band sends our best wishes to all of our friends who are on the other side of The Wall.” A cheer was clearly audible from the other side of the Death Strip. As the border guards looked on, the East Berlin crowd spontaneously chanted, “The Wall must fall!”

On 11 January, 2016, the German Foreign Office tweeted, “Goodbye, David Bowie. You are now among Heroes. Thank you for helping to bring down The Wall.” Bowie’s influence on this freak city continues to reverberate through every beautiful, hard-bitten corner.