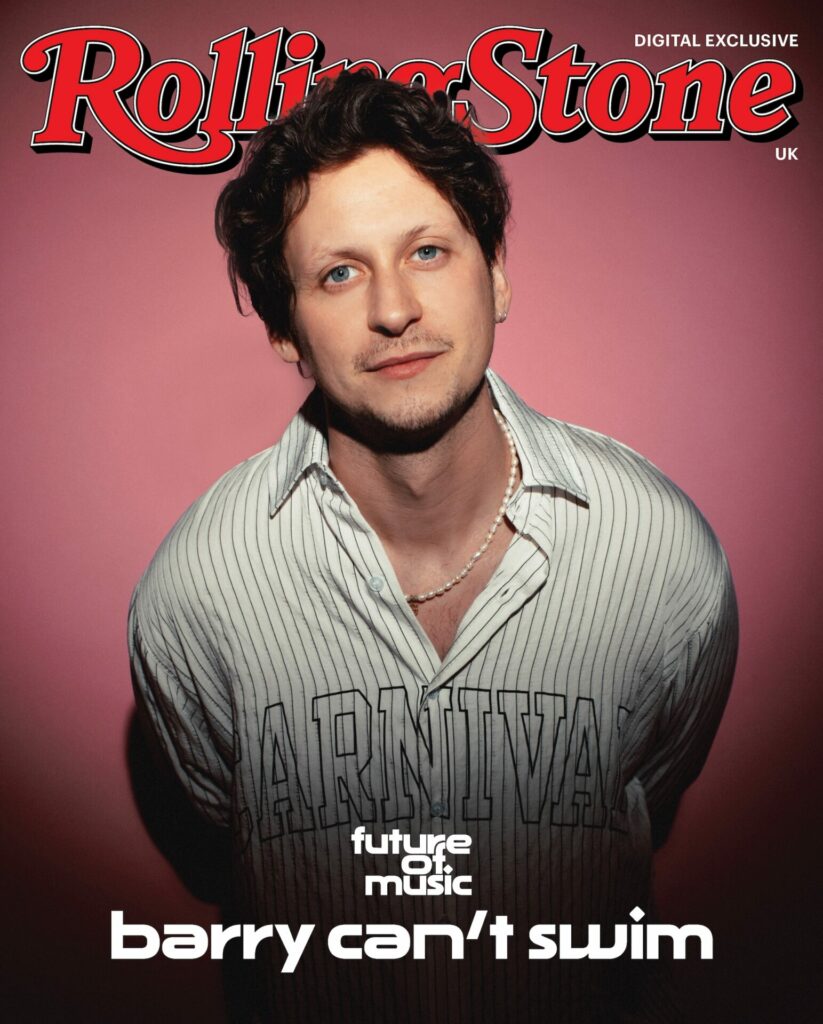

Barry Can’t Swim wants dance music to take itself less seriously

On the cusp of a breakout year, Joshua Mainnie talks trusting his instincts and how he finds true originality.

For years before he became Barry Can’t Swim, Joshua Mainnie couldn’t decide what he wanted. The Edinburgh-raised, London-based musician played every role in multiple indie bands while sharing his love of jazz and electronic music across a host of projects, before he made one of them stick.

“I get very bored very quickly,” the Scotsman chuckles over video call from Montreal, where he’s heading towards the end of a sold-out tour of North America. Straight afterwards, he’ll be into rehearsals for a new live show that will hit Glastonbury, Coachella and more. “If I ever started a project and it didn’t go in the direction that I wanted within six or nine months, I’d often drop it,” he admits now, even saying that “the Barry thing” didn’t have much conscious thought put into it at the outset. “When you start this shit, you don’t think it’s going to become your whole life!” he laughs. “I thought the name was a bit of a funny joke and just ran with it.”

Against his natural instincts, it looks like Mainnie will have to remain as Barry Can’t Swim for a long time. In the few years since the project’s inception, Mainnie has become one of the most buzzy and in-demand figures on the UK’s dance music scene, propelled by his eclectic and dazzling debut album When Will We Land?, released via Ninja Tune in late 2023. On it, he traverses jazz, club music and beyond with astonishing attention to detail. His live show, meanwhile, has packed rooms at home and abroad, as well as at festivals worldwide.

“What I’ve been doing has fortunately resonated with people in a certain way, and it’s made it easier for me to stay enthused by it,” he says. “You want people to enjoy what you do, and if you say you don’t, you’re kidding yourself. Why are you making music and releasing it outside of your bedroom then?”

In the past few years of the project, Mainnie has turned into a lauded and exciting DJ too, despite only learning the craft out of necessity during the pandemic when he was getting requests to perform DJ sets as Barry Can’t Swim and wanted to fulfil them. “It kind of annoys me when people call me a DJ,” he says. “I’ve been playing instruments for decades and was producing for five years before I even touched a set of decks. I really enjoy it now, and it’s a total art in itself, but I don’t think that being a DJ makes you an electronic musician or vice versa.”

His Boiler Room set from his hometown of Edinburgh is packed full of buoyant and playful beats, with Mainnie skipping around the booth with an ever-present grin. It’s this infectious energy and fun-loving nature that defines his sets, and it’s indicative of a wider trend in dance music in the post-pandemic world: artists are having more fun.

“I’ve always been somewhat disillusioned by the chin-stroking element of dance music,” he says. “I just think it’s a bit unnecessary, and a lot of the time artists themselves aren’t necessarily like that — it’s fans that attach that to us. I’ve never really had time for that. People are far too concerned with how they are perceived and how they look in that scene, and some of the love is lost along the way.”

For an example of the rubbishing of this ethos, look no further than when Barry went b2b with fellow Ninja Tune signing and Manchester-based producer salute (Felix Nyajo) for three-hour shows in Australia at the start of the year. During the sets, which caused roadblocks outside venues in Sydney and Melbourne, Mainnie and Nyajo had the absolute time of their lives while playing both cutting-edge house and club classics, their unrelenting energy bouncing off each other throughout.

“Part of the reason those sets have done quite well [online] is because it’s all really sincere,” says Mainnie. “We met for the first time in New Zealand just before and went for some pints, and I just came up with the idea of the b2b there and then. We ended up shutting the whole block down! When you’re bringing that energy, and it’s real, it connects with people.”

Alongside this burgeoning DJ career, Barry Can’t Swim is also set to bring a new and beefed-up live show across the world in 2024. “It’s not a typical electronic music live show,” he teases. “It feels really live, and it feels like a band.”

Trusting gut instincts and following what feels good is the guiding principle behind Barry Can’t Swim, and this idea is also evident across When Will We Land?. Though the music is packed with nuance and detail, it’s also a masterclass in trusting your first and scrappiest idea, none more so than on highlight ‘Deadbeat Gospel’. The track features the recital of a poem read to Mainnie by old friend and Dublin-based artist somedeadbeat, recorded at the drunken hour of 4am after a Barry Can’t Swim show in the city where he and his friend had reconnected after some years out of touch.

The recording is imperfect and scratchy, but it captures the essence of the moment and of Barry Can’t Swim’s ethos as a whole. Drunken revellers pass by, and lines are messed up, but when the pair tried to record a cleaner and more polished version in the studio for use on the album, the initial energy of the piece was completely sapped.

“It’s about happy accidents, right?” says Mainnie, with a smile. “I’ve thought about this a lot on a deeper level. Happy accidents are the only true form of actual originality. Everything that you’re consciously writing or doing is based on what you’ve heard before. Even the way that music scales in the West are completely different to what they are in India or other places. You can’t ever truly do something that’s completely fresh and out of the box, because it’s all based on what you’ve already heard. It’s in those little moments, when there’s some mistake in something when you’re producing, or something completely happens by chance and you just didn’t mean to do it, that you find something completely true.”

He adds, “What people are really asking for in their music isn’t something that’s hyper-clean and really polished all the time. They want to feel something when they listen to music, and that’s why you can still listen to music from 60 or 70 years ago, which objectively speaking is probably recorded pretty badly compared to nowadays. You can still feel so much in it though because it’s not really about that: it’s about the emotional connection. The fact that [‘Deadbeat Gospel’] is on a shit recording transports you further into that moment. Hearing him (somedeadbeat), re-do it in the studio, I just thought, ‘This could be anything.’”

This paradox at the heart of Barry Can’t Swim is also the thing that is making him a star. His music is deeply considered and lovingly crafted, but simultaneously an unconscious splurge straight from the heart and the hips. He’s a deep thinker but also wants to completely let go. What ties it all together, though, is a commitment to not being taken too seriously and having the maximum amount of fun possible. As Mainnie posits: if dance music is meant to make people happy and dance, why wouldn’t you also be having fun making it?

“I think it’s definitely a trend, but it’s not something that I consciously do. Maybe the world is just ready for that and it’s just worked in my favour,” he says, with the likes of salute, Fred again.. and I. Jordan becoming larger-than-life personalities as well as killer DJs, bringing character and energy back to the booth in a long overdue vibe shift. “The origins of dance music are about community, bringing people together, having fun and sharing an experience on the dance floor,” Mainnie says. “Sometimes in the more leftfield lanes of electronic music, that’s lost a little bit.

“You can still have fun and enjoy yourself and play credible sets,” he smiles, dusting off the shackles of the self-serious purists and hip-shaking his way into a summer that’s set to make him a star.

Taken from the April/May issue of Rolling Stone UK – you can buy it here now.