How meeting Arca blew FKA twigs’ world open

In this exclusive extract from Liam Inscoe-Jones’ new book ‘Songs in the Key of MP3’, he tracks a pivotal moment in the development of one of 2010s pop’s key figures

Alejandra Ghersi Rodríguez was born in Caracas in 1989. Alejandra’s family were rich. Her father was an investment banker who, in 1992, moved his family to America when he found work in New York City. When the family returned to Caracas six years later, the country was steeped in political and economic turmoil. Caracas was no longer the kind of place where children, even the children of the rich, played freely. Alejandra lived behind the walls of a gated community, attending the kind of private school where her friends rocked up with bodyguards in bullet-proof cars. Like twigs, Ghersi’s bedroom became a sanctuary. She’d play with a blanket: wielding it like a cape when her mum was looking, turning it into a skirt when she left.

Becoming Arca was tied closely to Alejandra’s self-acceptance. When she was seventeen she returned to New York to study. There, a shy and nervous teenager, she quickly came to be inspired by the icons of the city. One day, after spending hours sat in Chinatown café devouring a biography of Arthur Russell, she finally plucked up the courage to ask out a man she spotted on the Union Square subway. “That was like jumping off a cliff,” Alejandra told The Fader years later. “My survival instincts – everything I’d trained myself to do – were telling me not to do it, but something inside of me drove me forward.”

Around this time, Ghersi discovered GHE20G0TH1K: an underground club night which emerged in the wake of the financial crash. GHE20G0TH1K was conceived explicitly as an end-of-days party, replete with biohazard symbols, freakish costumes and soundtracked by garish, pummelling electronic music. Arca’s sound was born directly out of those nights. Feeling liberated by her experience of coming out, Ghersi began to make music again in 2011, only now it contained far more of the open-eyed debauchery being blasted from Venus X’s subwoofers.

The music of her first two EPs – Stretch 1 and Stretch 2 – was far stranger than anything she’d made in Venezuela, marked by clattering percussion and strange, depleted synth patches. Her songs did something far more unsettling than even Shayne Oliver’s shattered, maximalist remixes of Rhianna, reducing the kicks of dance music to ominous thuds and adorning them with spiralling, downtempo synth. Alejandra no longer sang but instead filled each track with fragments of voices, an attempt to find productive use for the ones inside her own head when her transsexuality was dawning on her: trapped between the person she was and the person her body suggested her to be. The effect of fragmented songs like ‘Tapped In’ and ‘Ass Swung Low’ is utterly bizarre: the sensation of pure paranoia captured in song.

In 2012, just months after she’d posted her first EP, Arca received an email from an associate of Kanye West’s who asked her to submit some beats for the rapper. At the time, West was spending a great deal of time in Paris, drawing from the cold utilitarianism of various fashion houses and concrete Le Corbusier lamps. In the wake of the grand, chart-breaking opulence of Watch the Throne, West decided to shoot in a far darker direction for Yeezus and his team began scouring the web for pioneers of the digital underground. A year after posting her music for free online, Arca’s name was listed on that year’s most talked-about record. Afterwards, Arca was asked to DJ at the afterparties of Björk’s Biophilia tour, and was soon invited to Iceland to work on her next album, the mournful, soaring divorce record Vulnicura. At twenty-five, she became its primary producer.

Aside from two enormous stars in Kanye West and Björk, the only other artist Arca agreed to work with in the first year of her career was FKA twigs. They first met over a coffee in New York City. twigs’ manager had sent an email to her with links to some of Arca’s music, which she didn’t listen to, but took the meeting anyway. At first, the meeting was incredibly business- like – twigs’ worst nightmare – but Alejandra was disarming. They had, it turned out, a lot in common. They were both fans of dance and liked many of the same songs. Within fifteen minutes, they forgot that they were at a work meeting and decided that maybe it would be fun to make music together after all. In the studio they established a sense of mutual trust. For the first time, twigs was at ease with writing something on the Tempest, and allowing Alejandra to find the fifteen-second section which could be expanded into a song.

The first music that they made together – the songs which would become 2013’s EP2 – were the first I heard of FKA twigs. My first encounter was ‘Water Me’. I remember it vividly. I saw the YouTube thumbnail before anything else. It was a picture of a woman’s face, tightly cropped and set against a teal background; a simple image if not for the fact that this woman didn’t look so uncanny. It was like she was a marionette. A tiny, open mouth with gap teeth and massive, teardrop eyes: big and oily black like a mollusc’s. When the video began to play, that head started to rock from side to side, slowly at first, but gaining momentum with each passing second. It was an unnatural movement, rocking faster and faster until it grew manic, snapping across the screen in a blur. Once it calmed again, the woman wept a fat, silvery tear which slid down her cheek, performed a loop around her chin and dropped off her face entirely, only to fall back onto her own scalp. When it hit, it burst like a cartoon raindrop, and her eyes swelled wider.

The music was no less disconcerting. ‘Water Me’ begins with an angelic, choral voice vamping up and down. It sounds saintly, but there’s something uneasy about it too. There was that tapping, mechanical drum loop, and the voices rise and fall into nothing, making it sound like a machine imitating a human. Then twigs starts to sing. Her voice is delicate, so delicate that it feels like it would blow apart in a breeze. In the time of Rhianna and Adele’s octave-shattering vocals, it was shocking to hear something so small. The words she sang expressed a vulnerability which matched her whispered tone. ‘He told me I was so small,’ she sings. ‘I told him: water me.’

twigs and Arca shared a taste for the weird, and the inexplicable details which define their sound come from myriad sources. The frantic percussive arrangement in the breakdown of another EP2 song, ‘Papi Pacify’, was inspired by twigs’ teenage tap-dance classes. Her bias for low-end in her music, on the other hand, wasn’t a matter of choice: listening to too much X-Ray Spex at high volume had given her chronic tinnitus, and made mid-range frequencies difficult to listen to, let alone work with.

Arca on the other hand drew several of her idiosyncrasies from the music of Venezuela. The way she programs sub-bass is inspired by the sound of the furruco, an indigenous drum played by rubbing a stick pierced through the skin of a large drum, creating a tone which is infrasonic and severe, just like the thick bass which quivers through the middle of ‘Papi Pacify’. On the other end of the spectrum, some of Arca’s most shrill moments are inspired by changa tuki: bright, frantic electronic music invented by the poor youth of Caracas to play at dance parties thrown in their slums. Changa tuki was politically demonised by Venezuela’s upper classes and so never truly made it out into the wider world, but it was music Alejandra had partied to as a teen.

Arca works at a rapid pace, which suited twigs nicely. She was inspired by Arthur Russell’s ‘first thought, best thought’ approach, and finishes songs in swift flashes of inspiration, happily trashing something which had taken five hours to make if it isn’t coming together. While making EP2, break- through moments happened fast, after hours of achieving little. ‘Water Me’ was made at the very end of a session where Rodríguez and twigs had spent all day simply sat in the room, chatting and making beats. They had half an hour left before the clock ran out and so they started playing synths: twigs on the Tempest and Arca adding overtones.

When the shape of the song was made, the words came quickly. twigs started each day by listening to ‘Walk On By’ by Dionne Warwick, reminding herself that one simple line could be as meaningful as twenty. With that song in mind, she began singing over the primitive instrumental and the whole thing was written in seven minutes flat. Then they put on a merengue tune and tangoed through the studio to celebrate. They hardly touched it again. “Once I start to think about it,” twigs told Red Bull, “it implodes on itself”.

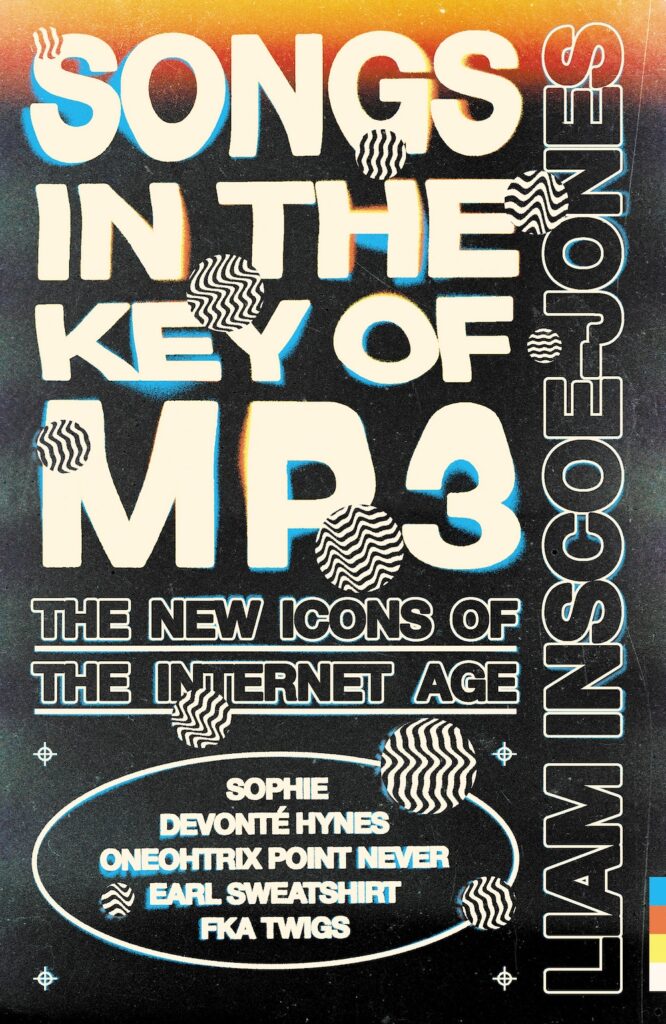

Songs in the Key of MP3 by Liam Inscoe-Jones is out now (White Rabbit, £20)