Speed, Self-Doubt and Andy Warhol: An Interview with Todd Haynes About His New Documentary On The Velvet Underground

American auteur Todd Haynes on how he delivered a dazzlingly immersive look into the world of The Velvet Underground

It’s not easy to categorise The Velvet Underground. How was one band able to influence both glam and punk rock and then continue to resonate down the decades, inspiring work as disparate as musical art pranksters, the KLF, and drone rockers Earth and Sunn O)))? They’re sometimes dismissed as little more than Andy Warhol’s house band but a documentary has arrived to help finally correct that – or at least add rich context to their rise and fall for a new audience. American auteur Todd Haynes (‘Safe’, ‘I’m Not There’, ‘Carol’) puts his vivid visual storytelling technique to work on his first documentary feature, simply titled, ‘The Velvet Underground’.

Andy Warhol was an important part of The Velvet Underground story. Although he was already a star of the art world when he first encountered the band as unknowns, he was by no means their Svengali. In them he recognised likeminded individuals, resonating with their dark, dangerous image of urban decay.

“Warhol didn’t make a musical contribution to the band,” says Todd Haynes, “he loved what he heard. The band had already found their sound when Warhol discovered them. He responded to the diabolical climate they summoned with their music. He liked the way the guys looked and presented themselves.” That said, his involvement was to have a huge impact on the band, particularly in terms of their visibility. “At [his art studio] the Factory he gave them a place to work and get deeper into what they were doing, surrounded by like-minded people. He gave them the grace of acceptance and encouragement. He gave them attention they never would have otherwise had.”

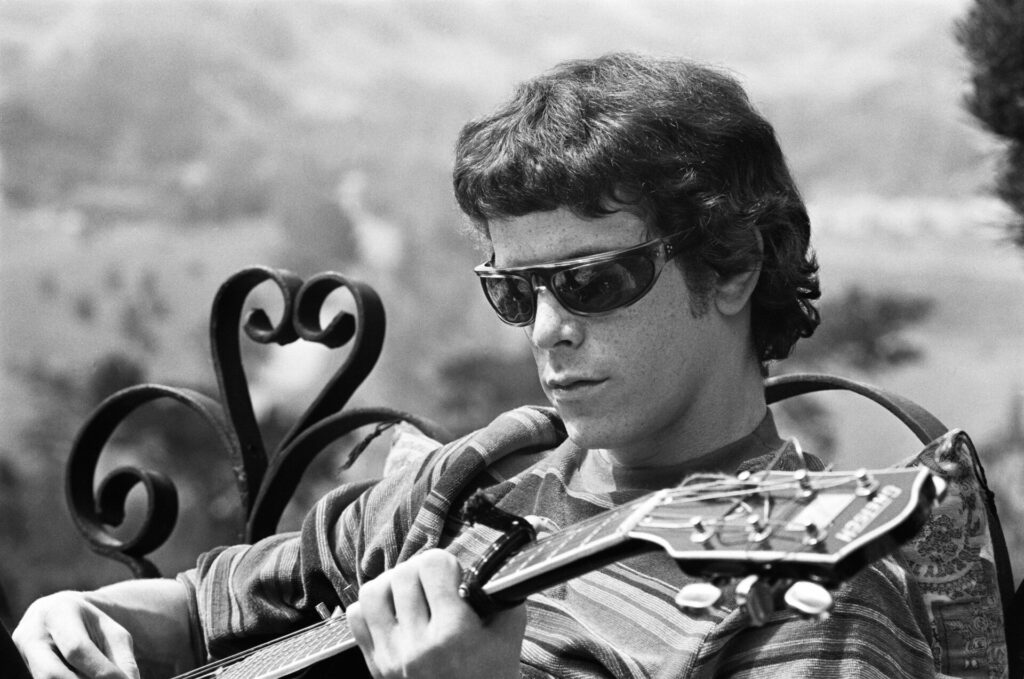

He was especially attracted to their lead singer, the sexually ambiguous and tormented Lou Reed. Like Warhol, Reed had grown up in a climate extremely hostile to his sexuality. But whereas Warhol created a shield between himself and the world with his art, and almost erased himself in social situations, Reed was more aggressive, both onstage and off.

“The hostility that’s most commonly described by journalists who had a hard time interviewing him over the years was already evident when he was a high school kid in Long Island,” says Haynes. “It wasn’t star behaviour – it was in his DNA. Those internal conflicts are also in the music. That’s why it occupied a place that nobody else was venturing toward, describing all sorts of self-destructive instincts, ambivalence and insecurities. His relationships with women were complicated and often sadomasochistic, and he had strong homoerotic feelings. But he went for it. He was the kind of kid who rebelled against his father by mincing around the room. In the 50s! That’s fierce.”

After college he worked at Pickwick Records, writing novelty rock records like ‘The Ostrich’, where he met Welsh avant-garde musician John Cale, and the core of The Velvet Underground was formed. ‘The Ostrich’ – recorded under the name Lou Reed and The Primitives – is prescient of his later output. It combines traditional rock with avant-garde musical elements to create an art prank. It’s similar to what the KLF would later do by critiquing the pop and dance genres while simultaneously creating great songs. Things moved quickly for The Velvet Underground when androgynous female drummer Moe Tucker joined the band, and then Warhol entered the picture.

Warhol created The Exploding Plastic Inevitable, a touring multimedia event featuring the band playing live while bathed in film, photography and stroboscopic light, accompanied by dancers brandishing whips. Looking at it now – presented here in all its glorious split screen intensity – it retains its dark power, an audio-visual ritual that bypasses reason and defies simple categorisation. Although the tour was short-lived and remained local to New York, its impact on future rock performances was huge.

The Velvet Underground’s album sales were poor throughout their brief recording career, a fact that belied their future status in the rock pantheon. “There’s a quote that’s often attributed to Brian Eno: The first Velvet Underground album only sold ten thousand copies, but everyone who bought it formed a band,” says Haynes. “We’re all inspired by great music and art, but it doesn’t all make you feel like you can do what you want to do, that there’s a place for your voice to be heard. There’s something about this band that made audiences feel that way.”

Even as the band gained momentum the cracks started to show. Warhol insisted that German model and actress Nico join The Velvet Underground, offsetting her angelic beauty against the Luciferian Reed. It may have caused tension but his instincts were proved correct; despite her untraditional singing voice, she surprised them all with her latent musical talent. The attraction she felt for Reed – combined with Warhol’s – also somehow helped to power this strange machine, even as it hastened its demise.

Reed started to question Warhol’s contribution to the band. “I think they began to feel like a novelty act,” explains Haynes. “Everything happened so quickly it seemed like maybe they were just a flash in the pan – another of Warhol’s crazy ideas to draw attention to his Marilyn Monroe paintings. But would they last? As it turned out, they changed the way we see art and culture.”

Then there were the tensions between Cale and Reed. These were partly because of artistic differences, but also due to Reed’s increasing difficulty in coping with his celebrity status. “I don’t think anybody on the other side of the divide can understand how feeling insecurity and self-doubt can persist throughout your life, amid fame and success,” says Haynes. “The adoration becomes abhorrent because it’s so isolating. It doesn’t give you room to create again.” And for Reed, the creative process remained paramount.

Their herculean drug intake – so much a part of the counterculture of the time – started to have an impact too. “The drugs they were using to keep themselves going had residual long-term effects,” says Haynes, “increasing anxiety and ambivalence and fatigue – all things that weren’t helpful for prolonging this moment, for stepping back and realising what was really best for them as a band. The intensity of everything was amped up – the speed of the times, the speed of the speed, all of it was in a concentrated form. What’s remarkable is that you see it in their output. Their first record was a comprehensive rock ‘n’ roll masterpiece. Each record that followed was a thoroughly conceived and produced artistic statement – they were almost concept albums. Four remarkable records in four years.”

Then as quickly as they appeared to transform the countercultural landscape, they quit. Thankfully their alchemical creative process – speed and self-doubt included – is plain to see decades later in Haynes’ definitive film.

The Velvet Underground is in select cinemas and on Apple TV+ globally from October 15th