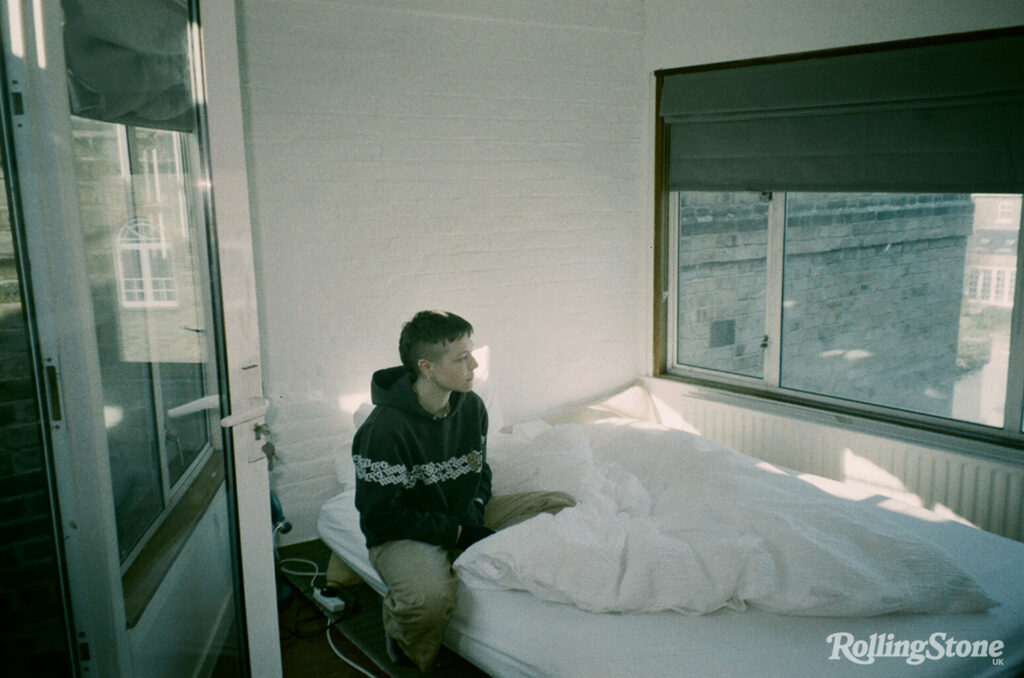

Love in a time of climate collapse: Alex Lawther on his timely directorial debut

End Of The F*****g World star Alex Lawther makes his writing and directing film debut with a fictional tale of love set in a dystopian time that is rooted in reality

By Molly Lipson

Sitting across the table from their partner Paul, activist Jenny is struggling to verbalise an intense feeling that’s rising inside them. Eventually, unable to contain it any longer, they burst out with it: “I love you. But today you come home talking about your day and asking me if I know my plans for the weekend. And I start to panic because I think, ‘That is the fucking problem. Plans for the weekend is the fucking problem.’ Meanwhile, I’m longing to make some sort of plan.”

This dilemma — trying to place the mundanity of weekend plans into a world newly understood as collapsing under the weight of existential climate change — is the central focus of actor Alex Lawther’s writing and directing debut, For people in trouble.

The short film unravels the love story between Jenny, a climate activist, and Paul, a more apathetic bystander. Jenny, played by House of Dragon star Emma D’Arcy, is struggling to conceptualise how to continue living their day-to-day life in the face of the devastating reality of climate collapse. Paul, portrayed by See’s Archie Madekwe, whose family is directly impacted by extreme weather events, would rather dedicate time and energy to building a life with Jenny.

Climate change has long been in the news, but for Lawther — known for his roles in Black Mirror and The End of the F***ing World — the 2018 International Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) report was a crucial turning point. It warned us that we had only 10 years to contain global warming below a catastrophic 1.5°C. Such a time stamp on the climate emergency hit Lawther hard.

Art was immediately a part of the actor’s response. Shortly after the report came out, he was asked by arts-based climate group Culture Declares Emergency to do a reading of a real letter a boy had written to his father after reading the IPCC report. In it the boy stated that he wasn’t angry with his father — and his generation — for creating such destruction, but that as a result he and his own generation had no future. “I found it incredibly moving not only to read the letter but to be part of creating a piece around it,” Lawther says of the event in April 2019.

Climate change isn’t about the future; it’s affecting people now, here in the UK. The burning of fossil fuels doesn’t just cause CO2emissions, but pollution too. Around the world, this causes nearly seven million people to die prematurely, according to the World Health Organization, with women and children and marginalised communities particularly affected.

In 2013, Londoner Ella Adoo-Kissi Debrah died at the age of 10 from an asthma attack. Her death was the first — and currently only — fatality in the world to be formally attributed to air pollution, the tragic result of lethally poor air quality in the area of Lewisham where she and her family lived, metres from the South Circular.

Since her passing, Ella’s mother, Rosamund, who fought to get air pollution put on her daughter’s death certificate as a medical cause, has dedicated her life to political advocacy. In summer 2022, she went to the House of Commons to hear the second reading of Ella’s Law, a Bill that would make clean air a human right.

Elsewhere in the UK, rising sea levels, another consequence of carbon emissions, are creating much more visible problems, and yet very little is being done. A map created by Climate Central shows areas of the country that will be one metre underwater within 30 years. Incredibly, this includes cities as far inland as Peterborough and Doncaster. In Skipsea, a small coastal village in Yorkshire, this threat is much more imminent. Retired sales manager Peter Garforth has been battling the elements — and the government — as the cliff at the end of his road has depleted by half over the past 20 years. Due to coastal erosion caused by rising sea levels and more frequent volatile storms, his house and others on his street are at risk of falling into the sea.

Despite being dubbed the fastest-eroding coastline in Europe, the local council has not set up defences, claiming they don’t control the purse strings. Yet other communities nearby have had preventative infrastructure installed. “If some communities can have sea defences and other communities can’t, then it’s discrimination. It makes us feel like second-class citizens simply because we don’t deserve enough sea defences,” says Garforth. In March last year, the council announced that it is taking part in a £36m programme aimed at helping communities affected by coastal erosion, but it remains to be seen if or how Skipsea residents will benefit from this.

It was a similar story in the Welsh village of Fairbourne — in 2014, the local council declared it would have to be decommissioned by 2054 due to the high flood risk. In other words, rather than invest in protecting the coastline and the village, they would rather delete it off the map. Although this declaration has just been rescinded, it has left a deep scar on the local community. Stuart Eves, chairman of the Fairbourne Project Board, which meets with the local council to discuss the ongoing situation in the village, explains that when the decision was aired on TV, “the village was mortally upset”.

The disregard for places like Skipsea and Fairbourne is replicated to varying degrees around the world, particularly in areas inhabited by marginalised communities. Decisions about what land to protect and save, and similarly what can be destroyed, seem to be made on the basis of prioritising profit over community, of capitalist gain over human life and livelihoods.

Because we live in a world that thrives off socio-economic, racial, gendered and other types of hierarchies, we implement the same template each time: those least responsible for causing the climate crisis, predominantly marginalised and oppressed communities, are being most affected by both the consequences of global heating and the exploitative processes that are causing it.

It was during April 2019 — the same month as Lawther did his reading — that he first became aware of the Extinction Rebellion movement. He had already been thinking deeply about the implications of climate collapse on both the present and future of our planet. When Extinction Rebellion first took to the streets, shutting down swathes of central London, he went along to take a look.

This is where I met him, in the middle of the roundabout at Trafalgar Square, surrounded by tents and chanting with a touch of radical hope in the air. We became, and remain, good friends, and when he asked me to help on his short film as a script consultant, I was thrilled to contribute as a quasi-advisor on activism.

By that time, I had already been organising around social justice for over a decade, predominantly around dismantling the prison industrial complex — prisons and all the structures that uphold socio-economic and racial hierarchies. I came to climate action later, taking far too long to connect the dots between race, class and capitalism, and the environment (a disconnect much of the UK climate movement still suffers from).

For people in trouble spans some five years, starting on the day Jenny and Paul meet, moving through various stages in their relationship, and culminates in an emotional ending following Paul’s attendance at an intensely violent protest. UK producers Sam Brain and Giannina Rodriguez Rico joined the project, alongside Matt Damon and Ben Affleck as US producers through their production company Pearl Street Films. Big names for a film that started as something so much smaller.

The characters of Paul and Jenny were initially personifications of each side of Lawther’s internal dialogue, while the film became a way to externalise what it means — or if it’s even possible — to live and to love while paralysed by existential dread.

As an actor, Lawther is thoughtful and philosophical about the role his industry, teeming with its privilege, has in “doing good”. He was keen to figure out how or if he could use his platform to do something helpful. “As someone who for their living makes stories, predominately as an actor, [my thought process was], ‘How can I carry on doing that? What purpose does that serve?’ And I suppose in a slightly perverse way, I made something in order to try and interrogate that question for myself,” he reflects on the film’s genesis.

“I’d been getting into reading the likes of Jem Bendell who wrote about the fact that it’s too late to make any change, and therefore, it’s just about trying to find out how to cope with disaster rather than trying to prevent disaster from happening,” he explains. For many people, Bendell’s work bridged the conceptual gap between climate change and a climate crisis, the latter inspiring in Lawther an urgency to do something, while reckoning with the reality that very little, if anything, can really be done.

After being immersed in this thinking for some time, Lawther had to leave London for a shoot in Wales. Suddenly in a very different world, one that was far removed from these discussions, he felt isolated and alone. This is a shared experience —once you’ve understood the true extent of the climate crisis, it can feel like you’re in a parallel universe from those who have not yet grasped its full horror. He found comfort inan album by Susanne Sundfør, Music for People in Trouble. “I was really bolstered by the fact that there was a piece of art that could, in an indirect way, help me understand what I was thinking,” says Lawther of the Norwegian singer-songwriter. “It was a companion that I would listen to when I was in a place where I didn’t really feel like I could have those conversations directly with the people around me.” For people in trouble is an attempt to create a similar source of solace but in visual form. No one, least of all Lawther, is stating that art can solve the climate crisis, “but it affects people, and people change the world,” he says.

In the film, Paul mentions the deterioration of his family’s living conditions in Nigeria due to climate change. Initially, this was influenced by intense flooding in Bangladesh in the summer of 2021, around the time Lawther was writing and editing the script. When Madekwe was cast as Paul, Lawther chatted with him about his family heritage in order to root the story in cultural fact. At the start of the short, Paul mentions how his aunt is having to move house from Ibadan to Lagos, Nigeria, because extreme winds have blown the roof off her house. It comes across as an almost throwaway reference, highlighting the casual but devastating normality of this experience for many people globally.

The term racial capitalism — the idea of extracting profit through racial subjugation — doesn’t feature explicitly in the film, but there are glimpses of it. For example, when Jenny and Paul meet some years after their first drink together, Jenny jokingly wonders if the pub has become a “Blood and Soilers” meeting house, a name derived from the Nazi slogan of a racially defined national body (“blood”) united with land territory (“soil”). Posters adorning what was a fish stand on the pub’s patio read, “Close borders. Make England green again,” and, “Fewer people = more jobs.”

Lawther and I spent a lot of time thinking through this particularly unsavoury part of the creative process. These ideas belong to an ideology called ecofascism, an emerging and worryingly popular belief that uses the climate crisis as justification for a eugenics-based culling of the human population. At the end of the film, Paul speaks about a march he attended against sterilisation laws.

The film also touches on the global increase in authoritarianism, as state responses to protest become even more brutal than before. When forecasting the landscape in a not-too-distant future for this film, Lawther and I envisioned armoured tanks, snipers on roofs, arresting people simply for holding a placard. In hindsight, we didn’t go far enough. Much of this is already happening. “It was about moving into the future, but it was only ever based on things that are happening right now,” Lawther says. “The terrifying thing is, such are human beings that if you can imagine it, it probably already exists.”

And it does. Around the world, more than 1,700 environmental activists have been killed in the past decade, though this is likely an underestimate. These are disproportionately Indigenous and poor people, attempting to defend their land and themselves from mining, fracking, oil pipelines and logging. In other words, from profit-making, climate-destroying processes.Even here in the UK we’ve seen a radical shift towards criminalising protest. Violent policing has always been the de facto response to Black and brown-led protest, and the use of such brutality and criminalisation is now expanding. The Police, Crime, Sentencing and Courts Act received Royal Assent in April 2022, heavily curtailing our right to protest, and targeting already marginalised communities.

As Paul states in his final monologue, “To love is to resist.” Radical empathy for the global community is paramount in combatting this crisis, and all the others intertwined with it. Like art, like film, we need to infuse our thinking with more creativity, to think outside the confines of what we know and reimagine how our world could look.

We are simply not responding in a way that corresponds to the scale of the problem. Despite knowing the harm of excess carbon emissions, we continue our path of destruction because the processes that emit carbon are profitable. We favour solutions that are simply green iterations of the world we already have: electric cars, renewable energy, sustainable fashion. Although these make us feel like we’re doing something good, they mostly reproduce the problem. It is this truth that leads many of us working in climate and social justice to focus solutions on the underlying systemic and structural root causes instead.

For Lawther, his hope is that this film touches people in the way he was moved by Sundfør’s album — it’s why the film’s name is a tribute to that record. Knowing it will be watched by people interested in film for film’s sake and not just those already concerned about the climate, he hopes that more people will be drawn into the conversation. Having started making For people in trouble more than three years ago, it’ll be interesting to see how the debate has moved on. Maybe it will reflect something about the speed at which the conversation has changed — or hasn’t — or has accelerated or stagnated.

What’s clear is that we can’t afford to let the conversation around climate stand still. If anything, we must push the debate further than we ever have before. We must think more radically, more interconnectedly, more globally and more communally. We must focus our energies on the root causes of the problem and implement healthy, people-centric alternatives. There is hope in the organising work of Indigenous communities, frontline defenders and other justice-focused movements around the world. There is hope in art that inspires new ways of thinking, and there is hope in us, if we allow ourselves to believe that we deserve a better world.

For people in trouble will debut at the Tribeca Film Festival.