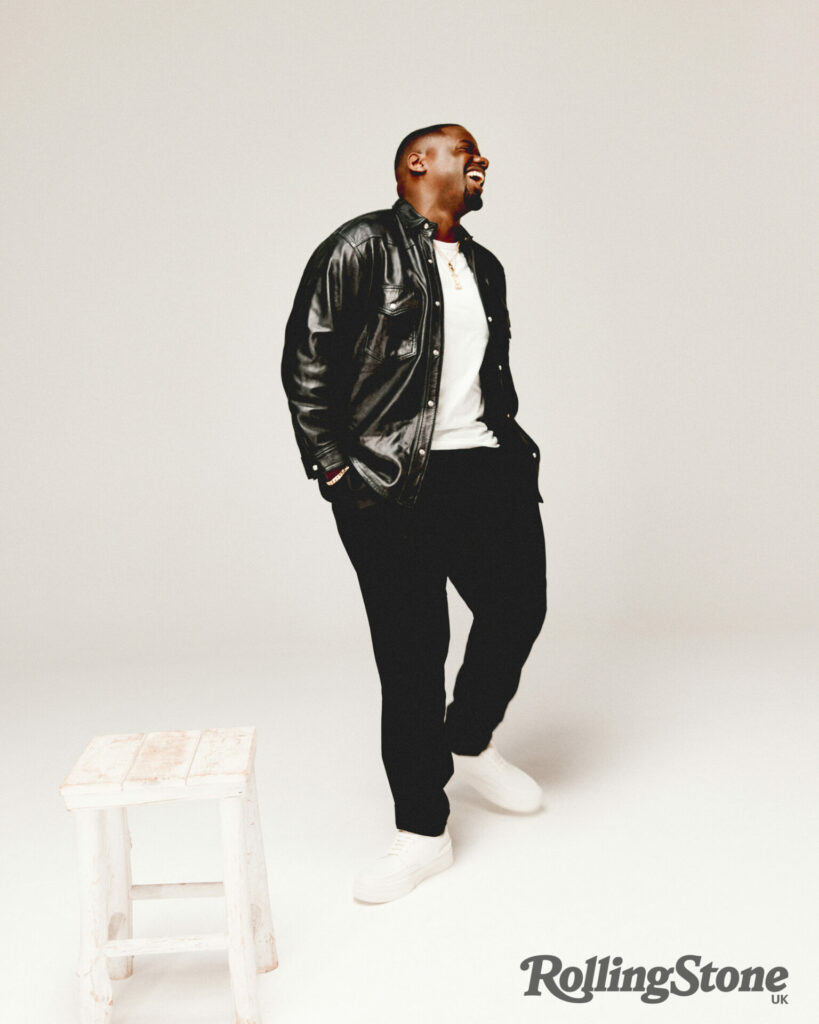

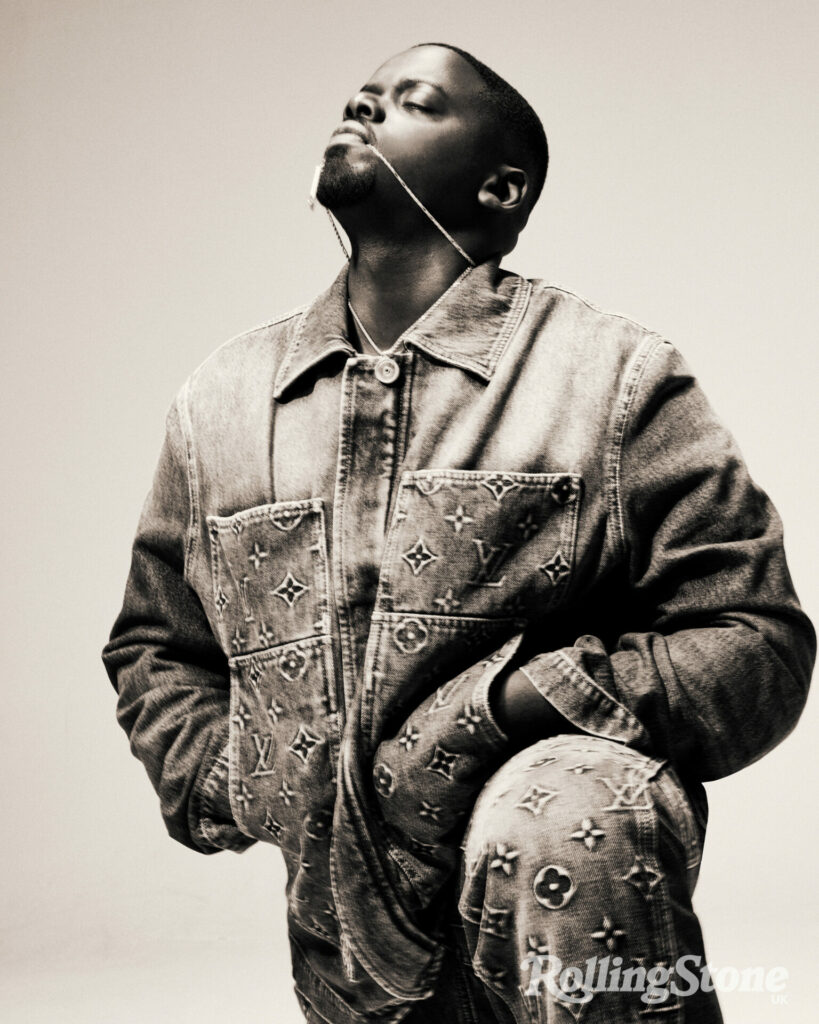

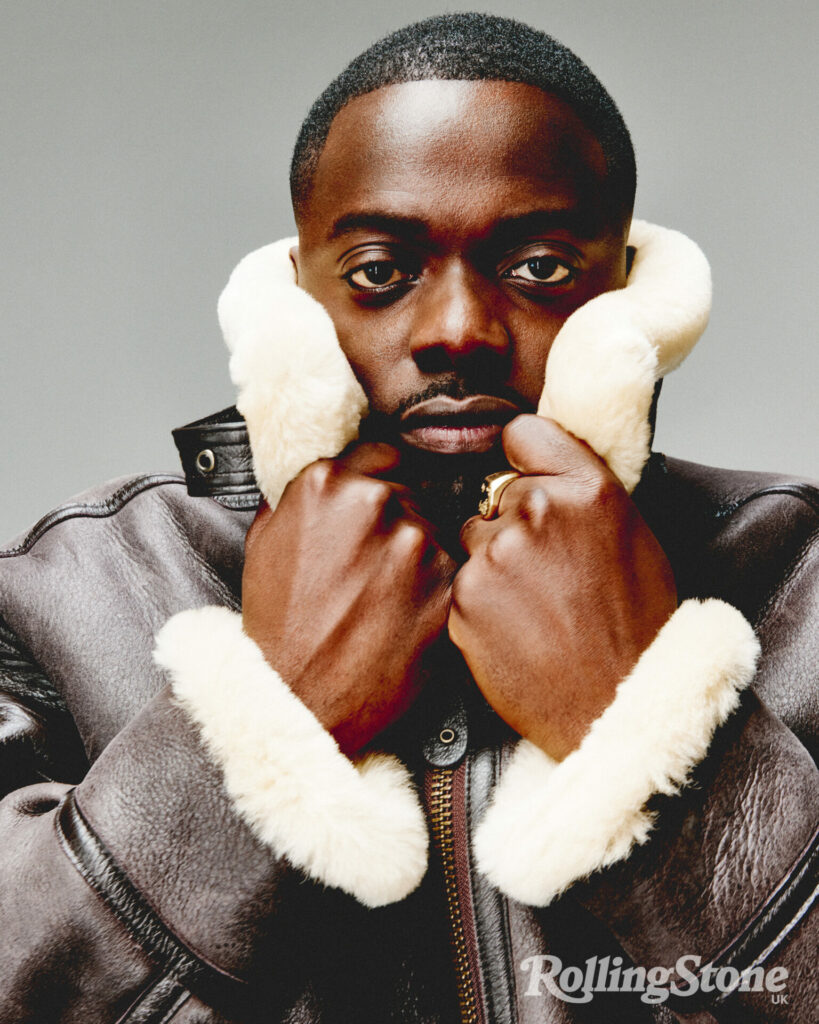

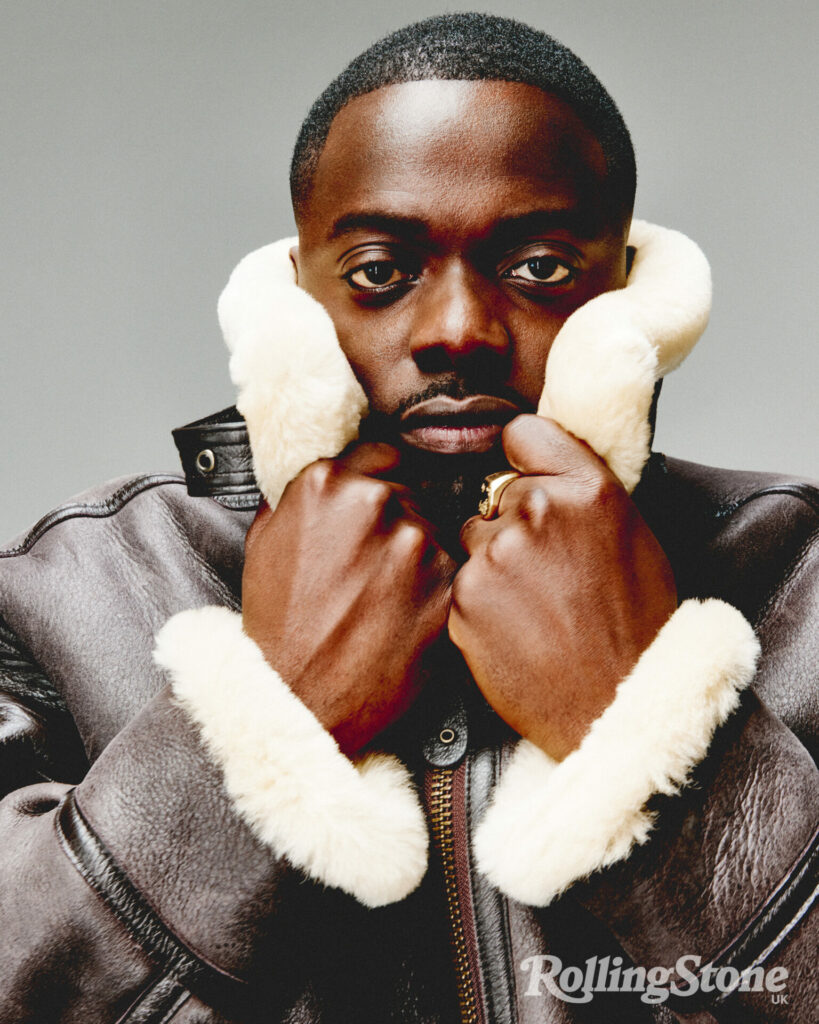

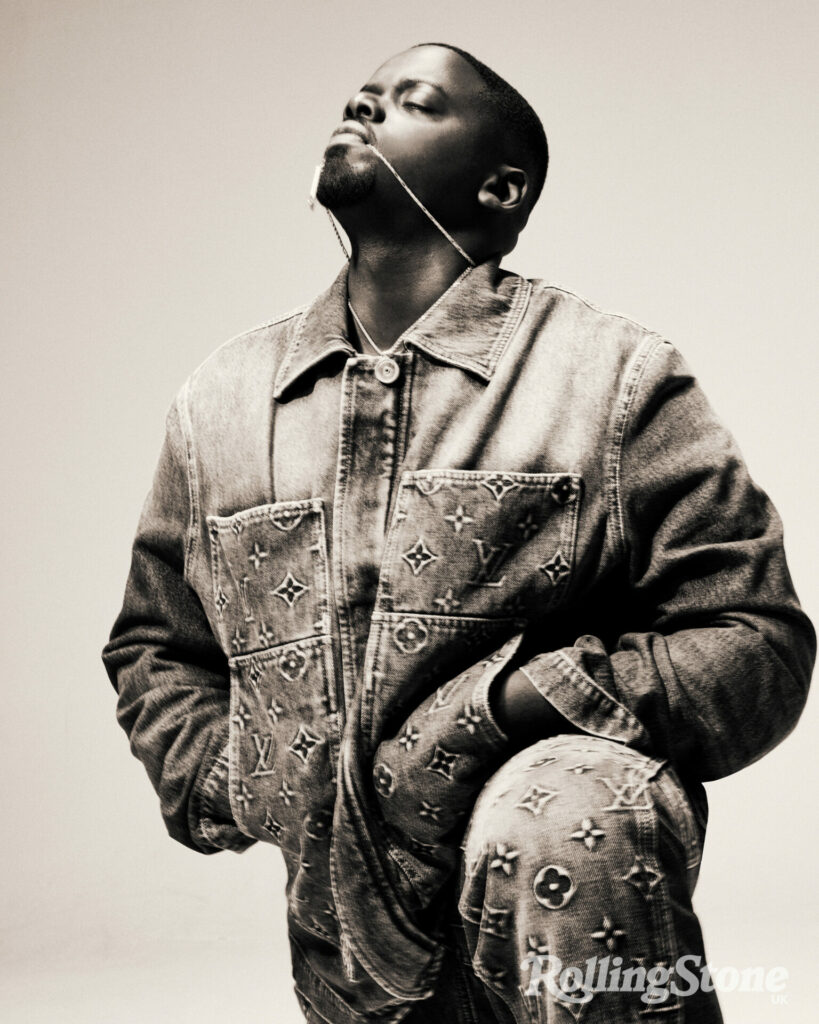

Daniel Kaluuya: the story so far

From cult TV show 'Skins' to Oscar-winner, Daniel Kaluuya’s career trajectory is the stuff of dreams. Now, the self-confessed storyteller has returned to his roots to direct his very first feature film, 'The Kitchen', a tale of Black British life in a dystopian London

I’m in a north London barber shop that has defied gentrification and remained in business for almost 30 years. Although this fact reveals his age, the shop’s owner, Nev, is only a little irked that he didn’t get a heads-up before his super famous client glided into his premises for our interview. As he punctually floats in off the street like any other guy, Daniel Kaluuya apologises: “You know how it is, Nev,” he says, in a covert reference to his A-list status. It’s the first insight I get into how Kaluuya navigates fame. Sitting in his long-time barber’s shop, he comes across like one of the lads. As a string of Nev’s regulars walk in, they each receive a brotherly nod of respect. No entourage, security or conspicuous Jeep have accompanied Kaluuya here, but his appearance provides clues to his celebrity — from how he holds himself, to the delicately embroidered name tag on his varsity jacket and the designer sunglasses worn backwards across what must be a fresh fade.

The barber shop represents more than the place where Kaluuya gets his hair cut. It’s where the seed was first planted for his latest venture and directorial debut, The Kitchen, out soon on Netflix after its premiere at the London Film Festival for the event’s closing night gala screening.

“Back then it was Reservoir Dogs in a barber shop,” says Kaluuya of the project’s inception. The idea came about after he overheard a conversation about the million-pound smash-and-grab robberies that targeted London jewellers. “I heard about the heists and how the guys doing it were getting £200. £200? That means there’s no one around that they can sell it to for a million. It said a lot about class.” It set him thinking about the thieves “who didn’t understand their worth,” as he says.

Rather than writing a traditional film treatment, Kaluuya shot a “taster” here in the barber shop to “show the idea in the medium that it’s going to be digested in — none of this coffee shit”. With a low chuckle that frequently warms our chat, he lovingly recalls the condition he had from boss man, Nev. “He would’ve given [the location] to me for free, but we threw him some change. I remember him saying, ‘Just don’t cut me out!’” As promised, Nev appears in the film numerous times — more of which later.

Not even halfway through his thirties, Kaluuya, who turns 35 in February, has already garnered the kinds of accolades that tell a poster-boy success story, making him the obvious choice to win The Film Award, in collaboration with Rémy Martin. After playing Posh Kenneth in Skins — he also co-wrote a number of episodes — he won big-screen roles that have carved a new cinematic language by meticulously exploring the historical and contemporary Black experience.

Get Out tackled the facade of Obama’s ‘post-racial’ America, looking at what it’s like to be Black in middle-class white society. Set in 1960s Chicago, Judas and the Black Messiah follows Kaluuya as one of the chairmen of the Black Panther Party. The film’s themes rode the wave of the Black Lives Matter uprising of 2020. Also, on that note, Marvel’s Black Panther, which centred Black characters and the Afrofuturism of its setting in Wakanda — a fictional country that imagined a world in which Africa had not been colonised — was bold in its take on the superhero genre, which until then had mostly revolved around white males and focused on the West. Kaluuya’s filmography is more than just impressive, it’s culturally significant.

While his previous work saw him explore American politics, with The Kitchen, the Camden Town-born actor has come home to platform Black British life with something he says aims to be “unapologetically us” with the “richness and complexities of our house”.

Whatever you thought you knew about Kaluuya becomes further enriched after viewing the film, which he admits without hesitation is his most personal work.

Along with co-writer Joe Murtagh (Calm with Horses) and co-director Kibwe Tavares (of Sundance hit Robots of Brixton), Kaluuya tells a dystopian story of a London that has sold its soul. All social housing has been eradicated, and the ‘Kitchen’ is the last of the blocks still standing. Despite orders to move out, many residents refuse to leave their homes. Although set in a near crumbling future, the date specifics were removed so people could “leave it to the imagination”.

Christian Louboutin. (Picture: Danny Kasirye)

Christian Louboutin. (Picture: Danny Kasirye)

On the film’s promo poster is the strapline ‘every city has its Kitchen’, a poetically solemn statement that begs to be unpacked. “We’re articulating something dynamic — that the people that are seemingly oppressed are actually resilient. They are joyful, but also don’t fuck with us! A lot of this was inspired by Liverpool and what they did with the Sun newspaper, where they just told everyone to fuck themselves. Then, it was the only northern city not to vote Brexit, and that’s not an accident. They have a unified identity.”

While this is a Londoner cherishing his version of the city, themes of gentrification, the widening rich-poor divide, grief and fatherhood are deeply embedded. Deeper yet, within this Valentine to a city that raised Kaluuya to be strong, lies an observation of the capital’s complicated roots.

Echoing the film’s strapline, Kaluuya says: “I feel like every city has a ‘Kitchen’, and I think because of the history of London and the Blitz, it’s more pronounced. We were bombed, and we survived. There are still traces of that within our being, but the class system dims us, so [with this film], I’m like, ‘Take the light and shine!’”

Is The Kitchen a warning as to where we are heading? “It’s not a warning. It’s happening! Before the Blitz, this is how London was. That’s what Dickens was talking about — poor against rich, and we’re going back to that.” As an example, Kaluuya highlights how Camden Market has had its soul watered down. “This film explores the idea that what if there was one bit that had the last bit of soul left?”

Kaluuya’s study of London’s history is most pronounced through former Arsenal football player and TV pundit Ian Wright’s character, Lord Kitchener, who he confirms is a “doff cap” to the calypso singer and the Windrush generation — not the former British Secretary of State for War. “There’s a lot of culture that is from the Windrush generation, let’s keep this real,” says Kaluuya. Having the person that’s the leader and voice of the community in the form of Lord Kitchener was representative of that heritage. Honouring the fact that Kaluuya’s cadence is Ugandan — he was born in London to a Ugandan mother — he acknowledges the “Jamaican influence” that many young Black Londoners will feel.

“In the grand scheme of identities, the Black British identity is new. Windrush was the 40s and 50s, so it’s new really in the history of the world. Now is the time I feel like we have to own our identity, own the fact that we are here, and this is what we’re about. And no, we’re not apologising for being here, and if you don’t get it, so what?”

Wright, with his Jamaican parentage, couldn’t be more suited to his role as a pirate radio DJ with the oratorical urgency of Samuel L. Jackson in Do the Right Thing. You’d be forgiven for thinking this was a ‘Gooner’ hiring his hero, as it’s no secret that Kaluuya is a huge Arsenal fan. “We did a podcast once, and I was so starstruck,” he says of the football legend. But Wright auditioned for his part like anyone else, so it was well earned, Kaluuya says assuredly. “With Ian, it’s about who he is, not what he does; he just happened to have done amazing things as well. That’s what was needed for Lord Kitchener’s role.”

The Kitchen’s representation of London’s hall of fame goes further than Match of the Day. Kano (yet another Windrush descendant) is cast as Izi, a brooding and distant dad, yet he’s still recognisable as one of the finest UK rappers to leap from grime to the big screen. After a dearth of decent representations of Black fatherhood, Kano (alongside an equally sensitive portrayal by Demmy Ladipo) delivers a refreshingly complex version of a man learning to be a parent to 12-year-old Benji (played by Jedaiah Bannerman).

Commending the results, Kaluuya explains how their linear shoot schedule helped crack the chemistry between the pair. “We shot as chronologically as possible. So, as they get to know each other, the bond gets deeper,” he says.

Improvisation was key to the authenticity of these scenes. Kaluuya is an alumnus of what’s regarded as one of the first acting schools for working-class kids, London’s Anna Scher Theatre, and has talked fondly of the improvisation techniques he learned there and still uses to this day. “It was all improvisation. When I write something — that’s the cut of the suit; then we get to tailor it. If I write a line and Jedaiah’s sitting there, and he doesn’t say it right, then throw it in the bin! Kano was amazing at that; he would just find some truth. In the last take, I’d say, ‘Do what you feel.’ The majority of the takes we used were from that because it’s fresh.”

Through these characters, Kaluuya says he wanted to be as “honest” as he could about fatherhood and “how messy it is”.

“If you’re a selfish man, you make certain decisions and there are repercussions,” he says. “Doesn’t mean you’re heartless, as the world has told him to be selfish. Fatherhood is earned. It’s not like, ‘Boom, you’re a dad now.’ It’s ‘Are you going to show up?’ I want certain men to come out and think, ‘You know what? I have that situation with the mum… allow it.’ We see Kano experiencing his son’s firsts — like his first rave — so then he’s like, ‘What else have I missed?’”

In a decade that has seen Kaluuya bestowed with an Oscar and an Oscar nomination, Golden Globes and BAFTAs, it’s little wonder why it has taken time for him to deliver his writer-directorial debut. “The Golden Globes, Oscars — that helped make this happen. What was that quote? ‘I want to stay clear of opportunities, so I can focus on my dreams.’ I had to think what was worthy of taking me away from this. It’s always been the most important thing to me,” he says of the stepping stones that paved the way to this moment. “Every shoot or play that I’ve been on, once finished, I’ve been back to this.”

How does it feel sitting here full circle in the place where it all began? “Nuts. Yesterday, I was still processing it, and today…” he inhales deeply, “more is coming.” Not that he’s read any of the reviews (apart from, he says, a glance at Rolling Stone on the way here). “It’s art. If the critics go, ‘Oh, this area’s not sharp.’ I know! I haven’t figured it out yet — it’s my first film. We’re young filmmakers growing and figuring things out, artists exploring our gifts. This is for the people. I want the people that this is about to feel it.”

Passionately expanding on the importance of authenticity, he says, “It had to feel like the people that come to this barber shop. I wanted to see as much of what I see outside on the screen. Every time I see something on the screen, I think, ‘This is fake!’ It doesn’t have the energy. So, I was like, ‘Why don’t we just use this?’” he gestures, signalling to where we’re sat. “‘What we love?’”

While The Kitchen has notes of hope, ultimately, it’s a snapshot of London in the dust and rubble. He has captured a zeitgeist as London pants with exhaustion from a prolonged Tory grind, and the cost of living crisis splinters society to breaking point. “I’ve been very blessed with a couple of different moments in films that I’ve done, but I realise when you tell the truth — it’s the truth! It may feel like things conspire, but we’re being honest about what we see.”

Music is one of the tools used to convey the atmosphere of the capital. The score, fashioned by Hackney’s Labrinth, features tracks that pulsate through nightclub scenes, providing a soundtrack familiar to anyone who frequented Bagley’s, Corks or Ministry of Sound, to name but a few of the nightclubs Kaluuya wistfully recalls. And anyone who’s been to an R’n’B nightclub will know the arresting power of the Candy Dance, so called because it is often danced to ‘Candy’, by 80s band Cameo. The Kitchen pays homage to the infamous synchronised slide. One-upping it from Spike Lee’s 1999 romcom The Best Man, which led to it becoming a wedding dance staple, Kaluuya has brought it home and placed the routine on wheels. Can he Candy dance in rollerskates? “No, I cannot! The Candy Dance is like church for the club. It’s the one moment where everyone will just stop and dance in unison. It’s like: how do you visually show a community having fun at the same time? I feel that was the way to articulate it. I love music. That’s what I wanted to get across — music is what London is.”

Inadvertently, to prove his point, we move to the pub next door where we’re shown a “quiet” table as loud Latin American music thumps from a speaker above. As he pauses to politely confirm that, yes, he is the guy from Black Mirror, I can’t help but wonder how he manages his fame.

“I never meant to make this my life. I do a lot of work to make sure I don’t lose touch with reality, but accept I can’t do certain things now,” Kaluuya says. “I realised I couldn’t get on the Tube after I had an argument — my third in a row.” He explains how camera phones have caused a shift in the culture of celebrity. “People film you on the Tube, and I’m a guy who likes a nap — I know the right stop to get off — it’s an art!” But it’s not his fame that causes the intrigue, “It’s because of the projects I’ve picked and what they mean to people that get the Tube. If I did Pride and Prejudice at The Dolman Theatre, I doubt I’d be bothered.” Apart from missing his naps on the underground network, what else does he pine for from the layman’s life? “Notting Hill Carnival,” he says immediately. “Fuck me, everyone who goes Carnival out there — enjoy that shit!”

We meet again the next day following his Rolling Stone UK cover shoot. He’s ready to wind down before heading off on a much-needed holiday. Channelling off-the-clock vibes and excited by the offer of food, we settle into a cosy King’s Cross cinema.

Returning to the theme of authenticity, I ask if Kaluuya sees The Kitchen as the beginning of a new wave of films that will represent multicultural London and its people. He pauses, contemplatively. “Guy Ritchie did it. Jonathan Glazer did it,” he says, going on to hail Shane Meadows as “the man” in terms of evocative British cinema. But he admits that those names aren’t showing a Black British London. “What I’m saying is, ‘Let’s not rely on them to tell our stories.’ Why are we waiting on them to do it? Why would they? We’re asking people who don’t know us to speak for us — it doesn’t make sense.”

Looking at the space that Kaluuya’s career has made for more Black experiences to be articulated on screen, I flag an interview from Essence magazine between him and Jordan Peele, where he had confessed to almost giving it all up. “A lot of my self-esteem was in other people’s hands,” he explains. “Even though I was achieving the checkpoints that I wanted, it was hollow because I didn’t feel ownership over my career,” he says. Speaking of the “rage” he felt, Kaluuya talks of finally taking some time out to find what he loves, which would include writing The Kitchen. It was a point at which he felt an existential shift. “I want to do it for people that are around me socially as opposed to professionally,” he reflects. “I realised I was getting respect from people that weren’t paying my bills or that would uplift me. All those decisions lead to the inevitability of fame. Because, basically, I’ve moved from self-serving to service.”

From a decorated actor to running his production company 59% via putting his name to youth theatre projects in partnership with the likes of Camden Roundhouse, what can’t he do? “I can do anything,” he says with his matter-of-fact charm. “I’ve always believed that. It’s how I feel about myself. I’m a storyteller. I just believe in my heart that I can do anything. I don’t know where it comes from. It’s just how I feel.”

The Kitchen is parallel to the cinematic styles that Kaluuya has become associated with. “Dystopian sci-fi suits my sensibility because usually there’s a lot of dark humour, and usually they’re bold enough to cast a Black person as the lead because… it’s fake,” he says, rolling his eyes. “But I love George Orwell. I love that satire. I love Chris Morris, Charlie Brooker. But I want to do a romcom, or more comedies, or just a romance.” I enthusiastically declare that I would love to see him do a romcom. “Make it happen! Tell people! I’m built for a romcom. I want to see incredibly cinematically crafted, amazing stories that are innovative and forward-thinking about love and about joy. I think that’s one of the main reasons I’m here. We’re in dark times, and love is needed way more than anything else.”

After this first taste of movie-making, Kaluuya is discovering what his directing style is. “I like bringing people together and helping people communicate. I’m sensitive, so I can understand when someone’s off. I’m very trusting in my team — I want them to show me shit I don’t know. Also, I like having a laugh. People make their best work when they’re happy. We’d have races, or days like ‘drip Monday’.” I pause. Despite our similar backgrounds and being less than ten years apart in age, I confess that I don’t know what ‘drip’ means. Humouring me, Kaluuya plucks the very nice fabric of what he’s worn to the shoot. Almost disappointed, he says with a laugh, “Come on! It’s where everyone came wearing their best clothes. Things like that that bring energy to set.”

As for his own mentors, he cites William Stefan Smith (director of the Kaluuya-starring short film Two Single Beds) and Ryan Coogler. “Ryan gave me advice that changed the course of this film. I really care about original cinema, but I was a bit too extreme at first. Ryan said, ‘Look, The Lion King is based on Hamlet.’ I was trying to make a whole new human and not accepting that a human has to have arms, fingers, legs. And knowing that there is biology and physiology to the storytelling and the structure. Only then you can maybe break the rules or put a twist on it.” Still staying true to his thespian roots, he also bigs up Second Coming playwright and director Debbie Tucker Green. “She’s incredible. When I wrote Skins, I was 18, and I didn’t know her, but she sat me down, and the first question she asked was, ‘How are you? This is a lot; you’re 18.’ Throughout this whole process, she’s always been checking in. [Theatre director] Sacha Wares too. I feel like theatre storytellers understand a story in a different context; they don’t have the bells and whistles, and I wanted The Kitchen to be as integral as that.”

On the future, Kaluuya is very certain about what’s next. “Whatever. The. Fuck. I. Want,” he says with that grin. “I’m not letting my occupation lead me. I’m an artist. I’m a storyteller. Where’s the story? Where do you want me to serve? I want to be multidisciplinary but that’s just being a London creative. Michaela Coel, she used to be a poet. Kane — is just Kano! We’re putting non-creative archetypes in non-creative roles. I don’t know what I’m doing, and I think that’s OK. What’s next? Everything is next.”

Taken from Issue 14 of Rolling Stone UK, our Awards Issue. You can buy it here.

Words: Corrina Antrobus

Photography: Danny Kasirye

Creative & Styling: Joseph Kocharian

Barber: Damon Elleston

Grooming: Jojo Williams

On-set style consultant: Cheryl Koneh

Lighting assistant: Henry Hewitt

Digital Assistant: Jem Rigby

Fashion Assistant: Aaron Pandher