The Mystery of Judas Pig: Stranger-than-fiction story behind cult crime classic

It’s the turn of the millennium and one of East London’s greatest true crime stories, Judas Pig, is being written. Its anonymous author, a former gangster, has a bone to pick with the criminal underworld who want him dead. Years later, fanatic online sleuths are still piecing together the book’s tantalising clues about unsolved murders, and searching for the whereabouts of the elusive writer.

Judas Pig can’t be many people’s idea of a light read. The novel opens with an origin story of sorts for its protagonist, career criminal Billy Abrahams. Born and raised in a south London sink estate during the ’60s, he describes a childhood of bare lightbulbs and angry black shadows — a world where the idea of nostalgia is a weak joke. We might recognise those as the halcyon days when nobody would steal a pint of milk from your doorstep. “That’s as maybe,” Abrahams relates, “but you’d still hear about kids going missing on their way to school.”

It marks the beginning of an astonishing book. Not just for its prose, though that’s memorable, too; a style that could be described as obscene Cockney noir, as if Raymond Chandler had moved to Poplar in the ’80s and lived to see the construction of Canary Wharf. Instead, Judas Pig’s power comes from a promise by its pseudonymous author, Horace Silver, that everything you read in its pages is, with the necessary alteration of names and dates, based on fact. Every heist and double-crossed deal, every beating and murder, drawn from the author’s direct life experience.

The book’s February 2004 release caused a major scandal in London’s criminal underworld. Its main characters — Abrahams, the psychotic Danny Longshanks and their sadistic firm of east London villains — were easily matched up to their real-life counterparts by anyone in the know. And it’s not often that a novel potentially holds the key to at least five unsolved murders. Judas Pig was the stuff of instant cult classic. Its uncompromising content was one thing, the apparent mysteries it contained quite another. Here was a series of puzzles for the enterprising reader to solve: who committed which acts of violence against who, and when? These are the riddles that have formed the basis of a committed online following devoted to the book and its author.

Back in the mid-2000s, there was another, even more pressing question to answer. Who was Horace Silver and why had he decided to write a novel so explosive that its reverberations are still being felt, nearly 20 years later?

Which brings us to a meeting between publisher Jim Driver and apparently retired gangster Jimmy Holmes in the mid-1990s. There are two versions of how they met. After all, it was a long time ago, Driver explains. The first involves Holmes approaching him at a book launch unannounced, Judas Pig manuscript figuratively in hand. Back then, Driver was running The Do-Not Press, a small and self-consciously edgy London-based indie book publisher, with titles ranging from photo essays on Shoreditch’s dying strip-club trade to the reminiscences of comedian Mark Steel. Judas Pig was one of their final books before they went out of business. “The story others have told was that I’d been sent the proposal and been so hooked by it that we planned to meet at the book launch,” Driver says.

Either way, Jimmy Holmes appeared to Driver as an unlikely debut novelist. The self-described ‘avant garde’ gangster had certainly lived a colourful life. These are the — at least fairly stable — facts. Holmes had been raised in south London, earning his stripes as a debt collector, before moving into Soho under the tutelage of Bernie Silver, an influential crime boss and pornographer of the mid-20th century. At some point in the mid-’80s, Holmes linked up with an increasingly notorious firm operating out of Canning Town, on the industrial fringes of east London. The following years form the basis of Judas Pig’s furiously intense, if impressionistic, narrative. Extreme violence is a fact of daily life, alongside the gang’s growing prestige and influence. Almost every page documents a bloody, often senseless beating, or its aftermath.

In Judas Pig, much as in Holmes’s life, bad beginnings don’t make for a respectable adulthood. The fictional Billy Abrahams looks quite a bit like his creator. Both become gangsters at the very top of London’s criminal underworld: shrewd, sadistic men living a relentlessly violent existence. No gruesome detail is spared over the course of the novel’s 351 pages. After the brief sojourn into the past, the opening chapter brings us up to speed, to a Soho amusement arcade on a teeming Saturday night, sometime in the mid-to-late ’80s. Abrahams weaves through traffic on a motorbike, with his sociopathic partner-in-crime Danny Longshanks riding pillion. A bullet to the skull puts an end to their prey, small-time hood Maltese Tony. They’re good at this. Gangland hits really aren’t that complicated, our narrator muses: “All you need is plenty of arsehole and the right tools. It ain’t rocket science. It ain’t any kind of science. It’s just killing. It’s what we do.”

The relentless brutality eventually wore Holmes down, as it does Abrahams in Judas Pig. The lines between fact and fiction in the novel are often blurred, but the ’90s saw Holmes decide enough was enough. It seemed to him that the thinly veiled ‘Longshanks’ — identified on the early Judas Pig forums as a very real, very dangerous, east London crime lord, as confirmed by the later reporting of the then Sunday Times journalist Michael Gillard — simply enjoyed hurting people, in a way quite beyond any business-led justification.

When Holmes finally fled the country, he did so with £100,000 belonging to his erstwhile business partner, an act which came with a mandatory death sentence. Despite the danger, he was back by the early 2000s.

In some ways, Judas Pig was an act of revenge. A brilliantly oblique act of guerrilla warfare against his former associates, bringing unwanted attention to a gang who had long operated in the shadows. After The Do-Not Press went bust, Judas Pig quickly became a collector’s item and its author retreated back into the shadows (not before publishing a follow-up novel, the vanishingly rare The Charity Commission) until Holmes was finally revealed as Horace Silver in the early 2010s.

After a few years of intermittent social media use, through which he would bait his old crew and occasionally correspond with Judas Pig fans, Jimmy Holmes vanished again. The last tweet from the Horace Silver Twitter account dates from 1 June 2017, sent to an Islington newspaper regarding an article about the murder of a local drug dealer.

Judas Pig was an act of revenge. A brilliantly oblique act of guerrilla warfare against his former associates

In a 2004 interview in the Observer, Holmes — still going by his pseudonym Horace Silver — dismissed the then booming trade in ghost-written gangster memoirs that had begun with the runaway mid-’90s success of Lenny Mclean’s The Guv’nor. “Any of these gangsters who have written books about their lives, they’re failures,” Holmes explained. “They’ve been caught and they’ve done lots of porridge and the stories they tell are no more relevant than Dick Turpin, because it all happened such a long time ago. Anyone who has made their money, they want to keep quiet.”

But Holmes had little interest in silence. As a novel, Judas Pig offered up creative possibilities that straight autobiography couldn’t, as well as a layer of necessary plausible deniability. This was a conscious choice by its author. No one who has dealt with Jimmy Holmes doubts his intelligence or erudition, and certainly not his criminal credentials. Tony Thompson is one the UK’s best known crime reporters and the first journalist to have had contact with Holmes, some time in the mid-’90s. The precise whens and hows aren’t something that Thompson wants to discuss, even today, though he’s happy to talk about the broader brushstrokes.

“I was working with him on some stories for Time Out, getting some insights into Soho gangs and criminality. We’d been doing that for a while, when he mentioned that he’d been working on a screenplay,” Thompson explains. It wasn’t a prospect that filled him with immediate enthusiasm. “This was around the time the Frankie Frasers and Freddie Foremans were coming out with their books and I thought, oh God, this will be awful. So he sent it in and I looked at the first page and it was called Judas Pig. I thought it was the worst title ever.”

These reservations melted away on first reading. It quickly became apparent that Judas Pig wasn’t your average gangster lit. “It was really visual, very well written. But getting a screenplay made by an unknown screenwriter is really hard,” Thompson adds. He explained to Holmes that he was better off writing it as a novel. “Holmes said, ‘OK, I’ll do that’ and I heard nothing for a while until six months later when he returned with a draft.” After a few bursts of revision, the book was almost there, ready to be sent to Jim Driver at Do-Not Press.

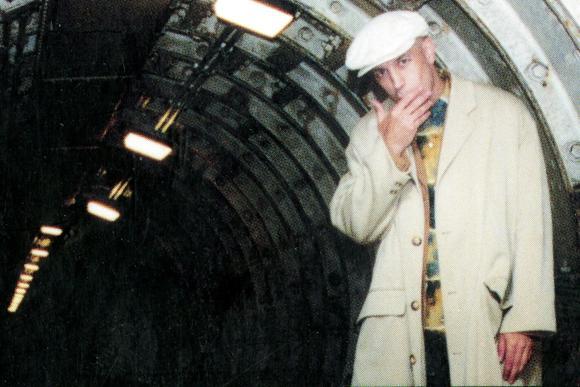

In 2019, a 37-minute interview with Jimmy Holmes was uploaded to YouTube. It shows the rushes of what became a short clip used for an episode of the Sky TV series Ross Kemp on Gangs, presumably filmed some time in the mid-’00s. It’s a charismatic performance, with Holmes breaking down a few home truths about the reality of the UK underworld. He’s cogent, clear and entirely without self-pity as he discusses everything from the mechanics of drug importation to attempts on his own life from his former gang. You can see why Thompson and others speak fondly of him. Men of violence are one thing. Those with the same capacity for charm and fluent storytelling, quite another.

Men of violence are one thing. Those with the same capacity for charm and fluent storytelling, quite another.

British true crime fandom is a complicated space to navigate, with its own unspoken rules and codes. The internet changed things: there were forums to speculate on, where friendships, or rivalries, might be made. Spaces where the amateur sleuth could be king, where a book like Judas Pig could live far beyond its initial print run.

The Judas Pig Facebook pages taken together have around 1,700 followers, clustering around the sporadic news. When the admin posted the news that Jimmy Holmes’ legal brief had passed away in March 2020, most of the comments came from exasperated readers trying to get hold of The Charity Commission. A quick browse of commenters reveals an international fanbase, male and female, from Wakefield to New York.

To this day, it’s difficult to accurately gauge the precise extent of Holmes’ own online output over the years. Michael Gillard interviewed Holmes extensively during the long course of his reporting on organised crime in the UK. “I’m not sure how much of it was him, or was ever him, and how much was a proxy. I just don’t know,” he explains. “He was on it and some of it was him. That’s because of his turns of phrase and his knowledge. But there have been copycats out there.” One of the other things, Gillard says, about “this new internet playground is that it’s being used by gangsters in the other way. To set the record straight or cause disruption or warn people off. It’s an interesting area.” Members of the Judas Pig fanbase have contacted Gillard in the past, telling him they’ve been warned off from digging too deep into the muck.

Threats aside, Judas Pig was, as it remains, the perfect forum text: a ready-made mystery with apparently infinite threads to unravel. Something different from the standard underworld hagiographies of the same time period, as well as the thrill of being near (but hopefully not too near) real-life gangsterism. “The problem with those books is that their authors usually want to come over well,” Thompson says. “Judas Pig doesn’t do that. It doesn’t glamorise or paint heroes. It’s shades of grey. There are people who are bad and people who are really bad.”

The lack of whimsical self-mythologising is part of what appealed to Dan, a long-time Judas Pig obsessive and a repository of knowledge for all things related to the novel and its hinterland. It started when he got hold of a copy around 2009. “It was a bit of a mystery to me. Everyone was trying to uncover the characters. There was an element of, is this made up or how much was exaggerated to get back at his former business partner,” he explains. Dan doesn’t want to reveal his full name, for good reason. The deeper one goes down the Judas Pig rabbit hole, the murkier the terrain. There have been occasions when Dan has received cryptic, if not outright threatening messages.

It’s just something that comes with the territory. When Holmes set up a website in the early 2010s, he inadvertently left his personal details on display. After Dan messaged a polite heads-up, he received a thank you in the form of a signed Judas Pig. Then they got to talking via the encrypted email service Tor, before the FBI took down the network in 2013. After that, Dan says, “We lost contact completely. There are still characters that haven’t been identified. I think that’s what holds people’s attention. It’s like an Enigma machine. There are bits you think are fictional, then something comes to light in the press and you realise that’s what Holmes was talking about.”

Getting hold of Judas Pig isn’t as onerous as it used to be. Amazon will take you straight to the reprint, as well as an easily accessible eBook version, even if first editions still occasionally shift for a significant price. Determining its author’s fate is something else. In the filmed interview, Holmes strikes a pessimistic note. It’s doubtful, he says, whether he or any of his old crew will make old bones. Those who have had dealings with Holmes are less sure, even if there hasn’t been direct contact for several years. There are multiple things that could have happened. The past could have caught up, in so many dark ways.

In autumn 2021, someone updated the Judas Pig Amazon page for the first time in many years. The only known person with access to the password was, is, Jimmy Holmes. The saga of Judas Pig remains what it always was: a grubby, if beguiling, mystery without any apparent end in sight.