Is It Time To Cease Fire In The UK Culture Wars?

Debating and dogpiling dissenters online and engaging with cyclical, clickbait mainstream media isn’t working. Progressive thinking appears to be losing. An alternative is needed

By Hannah Ewens

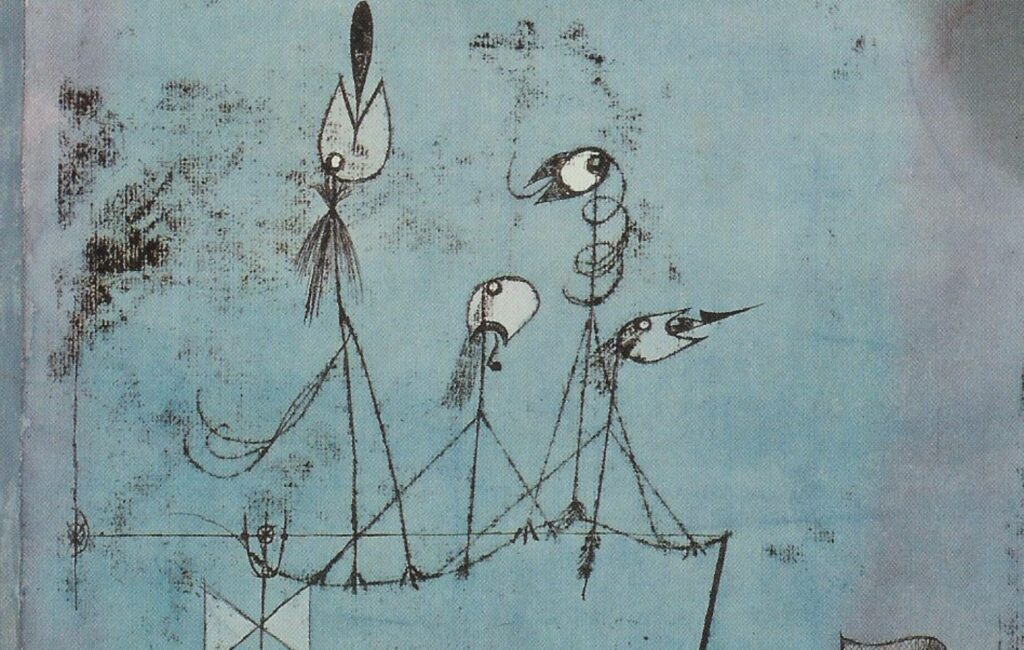

In Swiss-German artist Paul Klee’s watercolour and pen-and-ink oil transfer work Twittering Machine, a group of spindly birds balance on a wire that appears to be connected to a crank. Their strange tongues are in movement, the implied noises forced, at least in part, by the mechanics. It hangs in the MoMA in New York, which describes the 1922 work as a “violent marriage of nature and industry”. Its page on their site reads: “In this drawing, humans turn movement and song against nature, making them activities of enslavement.”

Some find the picture whimsical. Others, me included, feel it’s creepy and confrontational. According to a feature in New York Magazine in 1987, it was a popular picture to hang in the bedrooms of children, but I can’t imagine why parents would think maniacal birds are an appropriate night-time meditation for kids.

Klee’s picture provided the title for political writer Richard Seymour’s 2019 non-fiction book, The Twittering Machine. The ultimate horror story about social media, it tells how these systems prey on our weaknesses to steal away our attention and modify our behaviour. But just as there is something natural in the urges of the cacophonous birds, Seymour suggests that it’s precisely our humanity that can explain how addicted to the internet we are, and how argumentative it makes us. Or, as Max Read writes in his Bookforum review of the text, “Rather than asking what is wrong with these systems, we might ask, ‘What is wrong with us?’” Blaming social media is easy. We spend time on platforms like Twitter moaning about the platform itself and yet we increasingly spend all day on it. “We must be getting something out of it,” Seymour writes.

Seymour wrote this book in the second half of the 2010s, when the culture wars in the UK were solidified and made apparent by debate around Brexit. Now, settling firmly into the 2020s, the arguments he sets out in his book make even more miserable sense. On the surface, culture war issues are polarising disagreements. They suggest a country torn in two. When the media talks about them, it uses metaphors of warfare. They sometimes affect the lives of a small minority, for example, trans rights and debates such as whether trans people should have adequate access to gender-affirmation surgeries on the NHS or if trans women should be barred from women’s spaces in prisons or domestic violence refuges? More frequently, they’re complex histories reduced to loud examples that invite a yes-or-no opinion, as with colonialism — should we remove statues of slave traders or keep them in city centres?

The way we discuss these issues shows no sign of subsiding in mainstream media and on social media, only becoming more poisonous and divisive. As much as the mainstream media sets up these debates —by inviting people on panel shows to debate their existence, clickbait headlines that hyper-fixate on the same unimaginative questions — and social media algorithms reward outrage and engagement with them, it is us, the people on each side, that sustain them daily. It is real people who are at the heart of the culture wars.

For James Davison Hunter, the sociologist who popularised the concept, a culture war meant far more than mere disagreement. It was a conflict “over the meaning of America”. It signalled two irreconcilable and polarised views about what is “fundamentally right and wrong about the world we live in”. Similarly, Maria Sobolewska, Professor of Political Science at the University of Manchester, argues that the political right has not created the UK culture wars, as many on the left may occasionally believe. “These issues arise because of the two speeds with which attitude change occurs in society,” she says. Much of the ‘left’ side of the war look to the future, while the ‘right’ holds onto the past. This gap is now primarily seen between millennials (and Gen Z) and boomers (and Gen X) but was once even more extreme between baby boomers and their parents. The cavernous gap over which to shout at each other is not new, it’s that now with social media we increasingly see the extremes on these issues and from the people most invested. This is a battle played out publicly.

We know who keeps it alive from the left because we, reluctant people of the internet, see it every day. Activists, journalists, trolls, timewasters, students: all manner of people. The question is why? A considerable number of intelligent, media-literate users stoke the fires of this war constantly — engaging with bigotry, smugly outwitting opponents who may or may not be bigots or people in the middle — for a reason. It’s partly down to habit, but partly it’s because they believe they are doing something worthwhile. This is an enjoyable pursuit. “As far as the designers of these systems are concerned, if we’re engaging, we’re happy. It doesn’t matter what we claim about our preferences, the metrics tell the real story,” says Seymour. “And, in a psychoanalytic sense, we are enjoying ourselves even when it’s making us miserable.”

In a liberal and individualistic world, engaging in the culture wars offers social currency for doing so. It’s a quick way to create engagement online, to showcase your correct and socially acceptable opinions and position yourself as a brand-friendly authority. These are the routes to book deals, podcasts, business growth or larger, more legitimate platforms. Arts and media-adjacent workers of all political persuasions now go on to launch a career from grandstanding and quote-tweeting. There is a clear incentive in spending hours fighting with others and proving your point online — it’s become a legitimate and celebrated form of careerism on the left and the right.

It almost goes without saying that it’s difficult to engage with the culture wars without sounding morally superior, without slipping into familiar tones, shaming others or essentially calling them evil or stupid. “Outwitting or scolding reactionaries and bigots on social media is not an intelligent way of channelling aggression,” Seymour says. “Success requires more patience, more sublimation.” But patience is an unfashionable word when it feels as though we’re all running out of time.

During the pandemic, the culture wars have provided something like structure. They’ve given some individuals on the left a stage, a storyline and a hero’s role to play: they can feel as though they’re helping when humanity is facing extinction. There’s genuine comfort in that. But the war demands rapid engagement: there is no time to ascertain who is on the right, who is an aggravating troll hellbent on derailing everything, and who is in the middle, trying to understand what’s going on. Undeniably some people still use Twitter and the media as tools to learn. There are probably more of those people about than users imagine when scoring points on the internet.

As far as Seymour is concerned, engaging in this culture war model impedes efforts to build coalitions that cut across the boundaries of both sides. It encourages polarisation which tends to benefit only the right in the long run, “whatever immediate benefit leftist culture war entrepreneurs might get out of it”, he says.

For that reason, above all else, people must admit that they are personally gaining from the culture wars, whether it’s alleviation from boredom, indulging in self-destructive and harmful tendencies, career progression or the desire of the disempowered to feel like they’re “doing something” in a hopeless world. But collectively we gain nothing. If there is a culture war, the left is losing. When looking back at its escalation over the past few years, they can’t in all honesty say they weren’t willing it to happen.

It’s been six months since King’s College London and Ipsos MORI released the results of an extensively researched survey about the UK’s culture wars. The findings remain interesting in so much as they suggest that the average person doesn’t relate to the culture wars or know what they are. “Most people are not particularly animated by many of these issues, and many take a middle position or are not engaged,” the report reads. This is despite the “huge surge” in media coverage around the wars, with 808 articles published in UK newspapers talking about culture wars in 2020 — up from 106 in 2015. The caveat is that the public very much does care about the bigger issues such as immigration or Brexit.

Still, people are broadly reasonable: they are more likely to disagree that enough has been done in terms of equal rights for women and people from ethnic minorities in the UK. In both cases, that includes nearly a quarter who strongly disagree. Half the public think the UK is more divided by class than it was 20 years ago. But people who take a more liberal or left-leaning position on culture war and political debates tend to have the coldest feelings towards the other side.

Most importantly, the report focuses on the fact that the country’s population does not reflect the culture war’s polarity: 26 per cent are Traditionalists, the oldest and most heavily male and right-wing group, while Progressives – the left – make up 23 per cent. A larger group than either “side” is the Moderates who comprise 32 per cent. They support greater rights for women and ethnic minorities but less strongly than the Progressives. A further 18 per cent of the population is Disengaged. They stand out for their neutrality on politics and are apathetic on culture war issues. Not only do culture wars falsely reflect the country’s sympathies, then, but this information suggests that most of the population stand to be persuaded over to either “side”.

This is reason enough not to disengage with the wars completely. And Read warns against doing so: “The danger, though, is that in condemning this situation in general, you run the risk of dismissing important struggles (for rights, workplace protections, healthcare) as ‘culture war distractions’ because of the way they’ve been deployed in the platform context.” Trans people, for instance, are an at-risk minority group who are penalised by the right through the media, by the law and anti-trans vigilante activists online. To withdraw from the culture wars altogether could be dangerous.

Bobby Duffy, Professor of Public Policy at King’s College London, worked on the study. “It’s difficult to engage well, but it’s impossible to ignore,” he admits. “We have to engage with these cultural debates positively.”

What does engaging positively look like? Shon Faye’s new book The Transgender Issue sets out its own terms of debate regarding trans people. To avoid press outlets antithetically steering Faye’s book publicity into engaging with the debate around their rights, she was selective about each piece of promo itself. “I need to be convinced about what the benefit of this media ‘thing’ is for the book, for me, and trans people, if I’m being that noble,” she says.

The weekend before we spoke, Faye deleted her Twitter account because of the tiresome, harmful nature of discourse on the platform. On a personal level, disengaging from debate works. “Debate becomes polarised in this way when there are people in the middle who are really baffled and confused about the whole topic. Those are the people you have to persuade, not your audience of the people who broadly think what you think or someone who’s going to drag you into a pile-on.” There is power in leaving these spaces and reserving your resources. Or as Faye puts it: “I think that idea of being heard at all as ‘good’ isn’t true any more.”

Perhaps staying quiet and imagining something larger and more effective will allow us to take the first tentative steps onto the middle warring ground.

Duffy has read all the literature on the culture wars. His study suggested that our situation shows “clear echoes” of the US experience, with the UK in the early stages of a trend seen in the States in the ’80s and ’90s. The US literature is clear about both the problem and the remedy. “They all conclude with what you can do to improve the situation — and they’re pretty thin on that,” says Duffy. “But they all appeal to politicians, media and other influencers to cool things down and act more virtuously by not unnecessarily stoking up division.” He adds that this being the only solution suggests just how difficult that is to achieve. Even so, it would be “really dumb” to ignore the lessons we can learn from the US. Meanwhile European countries are up to speed, he says. Their people pay close attention to what unfolds in the UK via their TVs and newspapers, viewing it as an early signal of what might happen closer to home.

Conceptually, at least, Duffy’s remedy is simple. “People need to come together on complex issues and hear from public and experts and just have time to interact on it. It utterly changes the nature of the conversation you’re having.”

More effective activism currently taking place in the UK reflects that. In 2019, Lavinya Stennett founded The Black Curriculum to encourage the UK to provide better education around Black history. The organisation recently had an internal discussion about changing their approach to media engagement in order to stop articles about them being published with a possible clickbait title. “Our conversation involves longevity, not just a day’s outrage on social media. We have to be careful about what we say and what news we tie it to,” 23-year-old Stennett says. “We need an approach where there’s more dialogue, rather than statements.” This collaborative, thoughtful strategy is reflected in their current project: they’re providing parents with tools and the vocabulary to teach Black history to their kids.

What Stennett describes is a slow, kindly approach that resists saying parents are wrong or stupid because they don’t already have this information. We’re all starting from a proverbial square one, she says, let’s start together, somewhere.

Faye similarly intends to focus on those groups the researchers call the Moderates and the Disengaged. “This could get me in trouble,” she says, “but people do forget that you do need to persuade people in the middle or you’re not going to win, and that’s on any issue — whether it’s free broadband or trans stuff.” If you’re an activist, then conversing should be something done to help facilitate action, as seen with the global Black Lives Matter protests in 2020. But if like Faye, who does not consider herself an activist per se, you want to be helpfully discursive, she urges you to think about the terms of engagement.

“If you do just want to be discursive about things, make sure it’s on your own terms and I think that’s a hard thing if you’re involved in culture war stuff,” she says. “You end up speaking about things that you don’t even care about that much or that might not be a priority, in order to distract you.”

There are ways to extract yourself from the mechanisation of the culture wars entrepreneurial complex; to stop squawking because it feels like the only option. We are all far beyond blaming the algorithm or the right’s hold on the means of production. We have a chance to rethink the role we play as individual noisemakers, each part of an unhelpful collective front. At the very least, I think it would be nice to be free of the guilt of being at best unself-aware and at worst something as queasy as a culture-war entrepreneur.

“It doesn’t mean refusing to take sides,” Seymour says of the way through for progressive thinkers. It means refusing to be recruited, too easily impressed, refusing the impulse to court popularity or ‘act out’ in the public domain and certainly to avoid slipping into the dominant fetishes of our own side. “And remembering that whatever the issue, the knowing tone we adopt on social media is disingenuous: we know a lot less than we think.”