Hard Knox: how self-injury as entertainment captured our imaginations

A new book explores the surprising and previously unexplored territory of self-injury in culture and entertainment. In this extract from ‘Which as You Know Means Violence’, art critic Philippa Snow discusses the adolescent, self-destructive harm of Jackass’s Johnny Knoxville, alongside writer Hunter S. Thompson and filmmaker John Waters

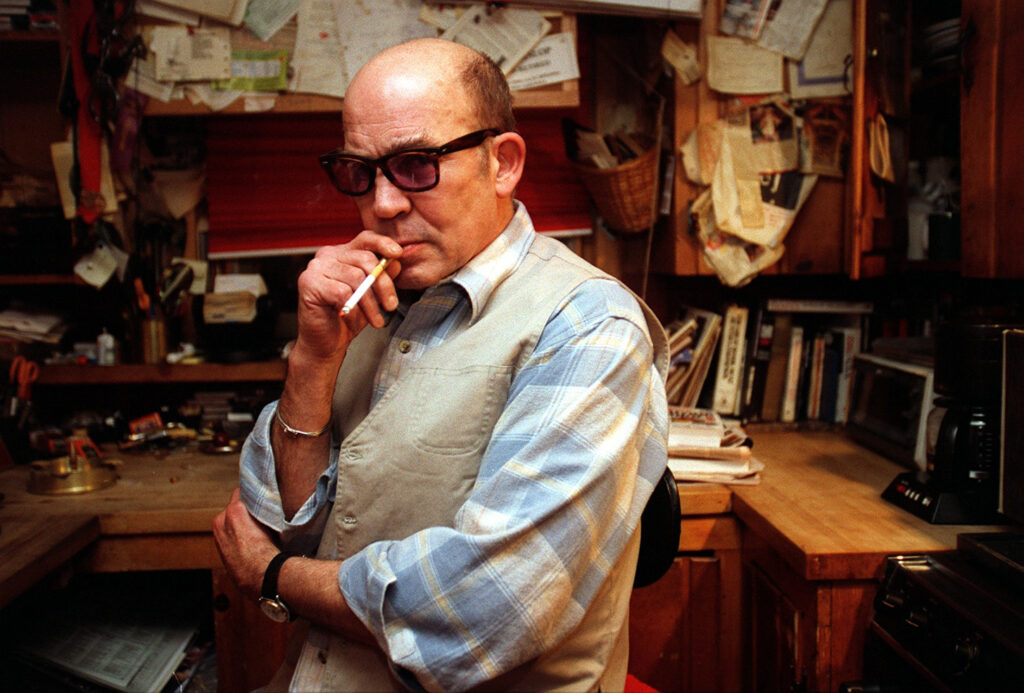

Three weeks before he died, Hunter S. Thompson left a message on the answering machine of another, less literary all-American counter-cultural fuck-up: Johnny Knoxville, the man best known for his role in the creation of the television series and film franchise about self-injury, Jackass, and less known for a career in Hollywood that peaked with an unedifying film based on the 80s show The Dukes of Hazzard. Thompson, the genius gonzo journalist whose mythic drink and drug consumption and percussive, breakneck prose occasionally overshadowed a keen eye for the particulars of politics and sport, had recognised a kindred spirit in the cocky, Kentuckian stunt artiste after the two of them went on an all-night bender in September 2005, in New Orleans. Knoxville, who for some mysterious reason cast aside his Pynchonian real name, P.J. Clapp — an appellation that seemed tailor-made to fit a stunt performer in a circus — in favour of a salute to his home state, had idolised Hunter S. Thompson more or less since adolescence. By the time they spent that night together in Thompson’s hotel room, drunkenly, bromantically reading selected passages from his Hawaiian odyssey The Curse of Lono to each other, Johnny Knoxville had become extremely famous, a putative redneck playboy whose idea of play was hazardous, extending to the kind of fun and games where somebody is apt to lose an eye. Magazines, noting his sharp-toothed, wolfish grin, likened him to a young Jack Nicholson — a comparison that would doubtless have pleased most men, but which would not have lived up, in Knoxville’s eyes, to being the heir to Thompson’s title as the sickest, most erratic documentarian of American life ever to earn the status of a household name.

In his very early 20s, Knoxville filmed a segment for the cult skate magazine Big Brother in which, standing in a neat suburban garden that seemed certain to belong to someone’s mom, he sprayed himself with Sabre Red, shocked himself with a 120,000-volt electric taser, and then drove out to the desert to put on a bulletproof vest and shoot himself with a .38 calibre Smith and Wesson at immediate range. The footage, rough and un-reconstituted as a snuff film, is at once a prototype for the aimless and unavailing self-destructiveness of early Jackass, and an accidental echo of a number of prominent 70s body art performance videos, most notably Chris Burden’s Shoot. Knoxville, who can be heard being called P.J. by off-camera friends — “P.J., it’s done,” one of them says, although he might also be saying, not wholly inaccurately, “P.J., it’s dumb,” — introduces himself in one languorous breath as “Johnny Knoxville, United States of America,” as if he were not a man at all, but an extremely scruffy metaphor: a walking, talking, self-abasing national id. Mailing the video to Thompson, he had been surprised to receive an encouraging phone call in response. A little later, the two met for the first time, fleetingly, at the Viper Room, the younger man admitting to having been “footloose, and a little overzealous” — an uncool and eager novice in the presence of a master. “He suspects,” GQ reported, perhaps underestimating how difficult it would be to perturb Hunter S. Thompson, “Thompson told his handlers to ‘keep that guy away from me.’”

Evidently, if Thompson felt any revulsion for the neophyte stunt actor, he renounced it over time; the sins of the father, when it came to bad behaviour, far outweighed those of the son. The two men shared a proclivity for some things — large quantities of alcohol, illegal and dangerous fireworks, lurid tiki shirts, and a very specific style of aviator shades that looked on Knoxville like a white-trash pastiche made by Gucci, and on Thompson like the glasses of a pervert — and a disdain for some others — personal safety, formal dress codes, what might loosely be referred to as The Man — and they were altogether two peas in a pod, in Thompson’s mind, when it came to possessing something called “freak power”. Knoxville repeated that message from his answerphone to an interested journalist in 2005, putting on “a scratchy Dr. Thompson voice”. That he appeared to remember the words verbatim was evidence of his awe, a lasting sense that he had somehow been inducted into greatness. “Johnny,” Thompson had reportedly informed him, “we were just sitting here talking about you, and then we started talking about my needs, and what I need is a 40,000-candlepower illumination grenade. Big, bright bastards, that’s what I need. See if you can get them for me. I might be coming to Baton Rouge to interview [imprisoned former Louisiana governor] Edwin Edwards, and if I do I will call you, because I will be looking to have some fun, which as you know usually means violence.”

“Fun”, for most people, does not usually mean violence. It is difficult to say what makes a person see the world the way Hunter S. Thompson did, except to guess that it may have something to do with an extreme attunement to the dark vibrations of a certain kind of American life, a folk song pitched at a dog-whistle that could only be detected by those who self-identified as outsiders. “What do you say,” he had written in the 80s, ruminating on the dual threats of the spread of HIV and acid rain, “about a generation that has been taught that rain is poison and sex is death? If making love might be fatal and if a cool spring breeze on any summer afternoon can turn a crystal- blue lake into a puddle of black poison right in front of your eyes, there is not much left except TV and relentless masturbation. It’s a strange world. Some people get rich, and others eat shit and die.”

Knoxville, born in 1971 — the same year Chris Burden made Shoot — certainly belonged to the generation Thompson was describing, making it entirely fitting that he and his Jackass cohort would get rich by masturbating, eating shit, and almost dying on a television show watched by 2.4 million viewers. Bloody, dumb, aggressive, screwy, simultaneously masculine and childlike, drenched in vomit and in semen, it is strange to think of Jackass having first aired in 2000 in light of its nihilistic attitude to modern American manhood, life and work — it too obviously resembles a post-9/11 show, with its giddy violence sometimes mirroring the helpless, hopeless mania that follows serious trauma. Notionally and geographically, it exists halfway between Venice Beach and Never-Never Land, making its bloodied knees and noses feel like natural by-products of its arrested, unpoliced environment. (Lest we forget: in J.M. Barrie’s Peter Pan, it is heavily implied that Peter murders his Lost Boys when they commit the crime of starting to reach puberty.) Its approach to injury is near-balletic, each sketch an elegant pas de deux or trois or quatre or cinq in which agony, and not ecstasy, is paramount. The pain — its white-hot, cattle-branding brilliance — is the point. The celerity of its pacing, fast and hard and engineered to appear loose, echoes the structural integrity of, say, the greatest hits of the Ramones: a pummelling, driving rhythm, built to induce something like an amphetamine rush, as carefully constructed as the sugariest single by a Spector girl group.

Early in its debut season, a baby-faced Johnny Knoxville can be seen wearing a shock-collar for dogs with his Ramones shirt, his incongruous prettiness lending him the unlikely air of a 00s stoner dropout who has been abruptly dropped into a punky, prankish remake of Salò, or the 120 Days of Sodom. “We’re going to convince [sound engineer Rick] Kosick that this is a piece of audio equipment,” he says straight into the camera, his tone as temperate and chill as if this were not an assault, but an experiment. “Unbeknownst to him, he’s gonna get shocked.” The way he says these last four words — his Southern-fried Tennessee accent turned up just so and feminised roughly 25 per cent, so that he sounds a little like Vivien Leigh as Blanche DuBois — unwittingly cements the mood of Jackass as a Freak Power franchise: an 18-hour fuckaround whose target audience had been young, disaffected men who wanted to watch other young and disaffected men affixing mouse traps to their nipples. The men of Jackass were frequently, nakedly homoerotic; they were dorky, skinny, more like boys who would be bullied than the alpha males most often seen meting out punishment. Knoxville’s crew included Ryan Dunn, Bam Margera, Jeff Tremaine, Brandon DiCamillo, Raab Himself, Steve-O, Preston Lacy and Ehren McGhehey, as well as a host of other daredevils with smaller parts, none of them leading men or heartthrobs, all of them cheerfully, grungily fatalistic. These men loved each other madly and fraternally, occasionally kissing, their desire for proximity appearing to arise from the muddling of terror and eroticism inherent in being made aware of one’s mortality — what the art critic Leo Steinberg described as “the condition of being both death-bound and sexed”. When the lawyers at MTV began suggesting that they could no longer perform stunts that seemed to risk their lives, they grew rebellious, migrating to a medium in which violence is and always has been less taboo than sex, hard drugs, political subversion, or the presence of non-white or unconventionally attractive leads: the movies.

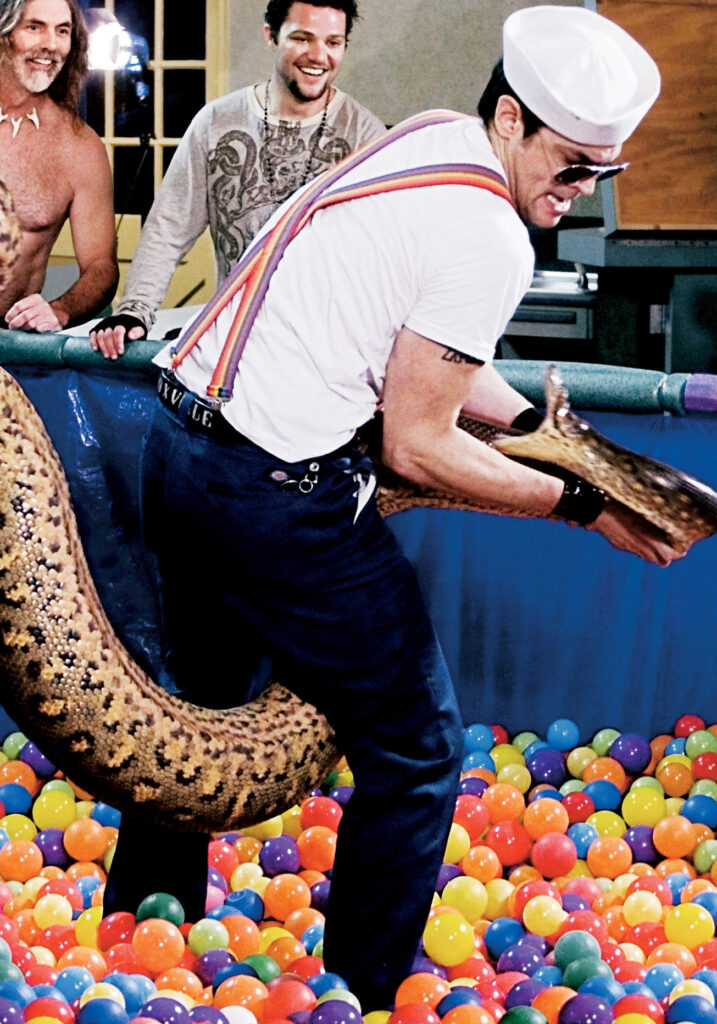

“Fiction,” Hunter S. Thompson once told an editor at Knopf, “is a bridge to truth that journalism can’t reach.” The Jackass films — a slickly made quaternary franchise whose second instalment is, of course, called Jackass Number Two — are not narrative so much as expressionist: long runs of sketches that intentionally or otherwise gesture at a bigger, more incendiary message about what it means to be a young man in America beset by the psychic indignities of economic downturn, terrorism, unemployment, hopelessness about one’s place in an increasingly dysfunctional society, and distant, quietly raging war. In the first movie, Knoxville rents a mid-range family car, pointedly choosing one whose paintwork is as white as untouched snow, and takes it to a smash-up derby, saying when he hands the car back by way of apology that he quite often “drink[s] and just black[s] out”. Later, a far less substantial car — a Hot Wheels toy — is inserted into Ryan Dunn’s backside, the setup for a gag about a druggy frat-house orgy gone awry. In the second Jackass film, Bam Margera has his ass-cheek branded with a cartoon penis by a sullen cattle rancher, and a nervous Knoxville dons a sailor outfit to wrestle with anacondas in a ball pool as the soundtrack plays the 1981 single by Josie Cotton, ‘Johnny, Are You Queer?’. (Subtext, by this point, has become sniggering text.) What many of the set-ups have in common is a dark ’n’ dumb, seditious take on traditional masculinity — the racecar driver, the cowboyish cattle rancher and the US navy man, all filtered through the sensibility of boy outsiders, never quite sturdy enough to make the team.

Hollywood, a metonym not only for the movie industry but for all things that are too good, too convenient or too bombastic to be real, seemed like the funniest place for these supposedly rough-edged and redneck daredevils to be performing stunts without protection, safety nets or training. Rarely has a cultural product felt more of the suburbs than the original run of Jackass, its dirtbag performers never looking like anything ritzier or more polished than a pack of local skaters who congregate in the car park at a mall. “We’re always trying to build a utopian society,” Peter Mascuch, the chair of cinema studies at New York’s St. Joseph’s University, once said in an interview with Newsweek. “And for the baby boomers, suburbia became that utopia. The flip side is the utopia never lived up to its promise. People became disenchanted, and then they react[ed] to that with critical and dark depictions.” A suburban adolescence, in other words, may have been a contributing factor in the Jackass boys’ desire to take aim at America by taking aim at each other’s tenderest parts: Gen Xers born into the failed utopia Mascuch describes, their depiction of the status quo was fated to be dark. “If this isn’t cultural terrorism,” the provocateur-auteur John Waters wrote in Artforum of Jackass Number Two, in which he had a minor cameo dressed as a rinky-dink magician, “I don’t know what is.” Ultimately, Jackass fitted into Waters’ legacy as snugly as a Hot Wheels car into a stunt performer’s rectum.

John Waters’ championing of Jackass is not terribly surprising — nobody will ever be as inextricable from the idea of eating shit, however many times the men of Jackass did so literally or figuratively. In 2004, Waters cast Knoxville in what has, to date, been his last theatrically released motion picture, also set in suburban America, a grossout comedy about a group of uptight, small-town prudes who hit their heads and end up turning into nymphomaniacs, fulfilled its purpose by being seen by almost no one; one last funny, filthy provocation from an offbeat national treasure. Playing Ray-Ray, a sex-fiend mechanic with a self-professed “hard-on of gold”, Knoxville achieves the balance every good John Waters actor hopes to attain in a leading role: a queasy mix of sex appeal and pure revulsion. The film did not end up heralding a move into the arthouse for the stuntman; what it did show was that Waters had identified his most sensual and insoluble quality, a merging of haute American masculinity and knowing, playful deviant drag, underpinned by what was apparently an interest in high culture. “Johnny is great; he’s a sweetheart,” Waters told an interviewer from a New Zealand newspaper in 2011. “He’s sensitive and funny.” Knoxville’s willingness to, say, wrestle in horseshit seemed at odds with his avowed love of the French New Wave and Flannery O’Connor. (Ernest Hemingway, he would insist, was far “too macho” for his taste.) Meet Jackass the Sophisticated Dude; You Want Rowdy and Moronic? Johnny Knoxville Is Poised and Bookish, if You Please, the New York Times trumpeted in 2002, noting how at ease he appeared ordering his meal in French at La Grenouille. The following year, the Times, alongside anecdotes about him covering his genitals with bee attractant, noted that Knoxville had been moved to leave his hometown after reading On the Road, and that when he first went to LA it had been to write a novel. Every profile seemed to ask a similar question: what is Johnny Knoxville’s deal?

It would take Knoxville 15 years to get around to even trying to provide an answer; that the question is, in many ways, the same one underpinning this particular essay makes his revelations on the subject doubly piquant. “I started to think, ‘Why do I love it? Am I addicted to it? Is it coming from a good place?’” he told David Marchese in 2018. “I don’t want to overthink things, but I don’t want to underthink them either because in this line of work you only get so many chances… Some other actors do their own stunts, but the difference is that their stunts are designed to succeed.” He had been filming Action Point, a movie about an unregulated theme park for which he had done his own stunts, ending up with four concussions, whiplash, stitches, a destroyed knee and a shattered wrist, and two-and-a-half broken teeth. One day, blowing his nose after discovering it was bloody, he felt his left eye pop, grapelike, out of its socket — “I was blowing air around my eyeball,” he explained, “and pushing it out” — forcing the crew to shoot him only from the right side for six days. He had just turned 47, and if he had looked like Jack Nicholson circa 1970 in the earliest days of Jackass, he now looked a little more like a car salesman who had been beaten up by a gang of flunkies over money at the racetrack. It had begun to occur to him that death was not an abstract possibility, but something real, the bloody bloom rapidly wearing off the rose as far as self-harm was concerned, now that a colleague — Ryan Dunn, who crashed his 2007 Porsche 911 GT3 in 2011 and died at 34 — had lost his life, and several others had developed debilitating addictions to painkillers, or dependencies on alcohol, or real-deal longings for annihilation that could not be satisfied by taser guns or vomit omelettes. Somewhere between head injuries on the set of Action Point, he had begun to think about his dying mother, and about the way his own children might feel if he ended up sacrificing himself on the altar of a 90-minute comedy about an unsafe theme-park with a 19 per cent Metacritic rating. He tells Marchese that he realised something: “I may have a little left in me. But for my sake and my family’s sake, I should start winding down.”

Thus, Johnny Knoxville ended up adopting another popular American pastime, newer than the nation’s lust for violence and a little older than its history of stunt performers: he began to see a therapist. “‘I don’t want to fix the part of me that does stunts,’” he recalls saying. “‘Just to get that out in the open… That’s what I don’t want to fix.’” In that interview with Marchese, he is coy about what drives a man to throw himself into a children’s ball-pit full of snakes, or deliberately crash a motorcycle, or split his head open “like a melon” on the concrete floor of a department store, save for saying that some of his impetus to destroy himself is almost certain to emanate from a dark, “unhealthy place”. The reader, left to fill in the blanks, invariably imagines some formative, terrible event that shook these strange desires loose — a childhood injury, an accident bloody enough to scar the mind. David Lynch, the dark suburban yin to Waters’ camp suburban yang, has said that as a child he saw a naked woman staggering down the road at night outside his house, “in a dazed state, crying”. “I have never forgotten that moment,” he told Roger Ebert in an interview in 1986. He has not allowed us to forget it, either — in Blue Velvet, Dorothy, a nightclub singer and rape victim, is seen stumbling past the verdant, manicured lawns of her younger lover’s neighbourhood stark-naked, evidently in distress. If not all artists make such deliberate connections in their work, re-enacting and restaging these determinative, generative moments as if all art were true crime, it cannot be denied that many of them enjoy gesturing elliptically at their own histories.

What is certain is that when practitioners turn to self-injury, or to the risk of death, the reasons tend to be one or more from a certain laundry list: trauma, Eros, infamy, national identity or history, parental influence, an interest in religious martyrdom, and war. “Art,” Leo Tolstoy wrote in What Is Art?, “is a human activity consisting in this: that one man consciously, by means of certain external signs, hands on to others feelings he has lived through, and that other people are infected by these feelings and also experience them.” “I feel like the injuries, I share with people,” Knoxville told GQ in 2021, unconsciously echoing Tolstoy. Although he clarified that what he meant was that his various breaks and scrapes and dick-destroying accidents had happened “in a public way”, the implication of a psychic bond between the audience and the stuntman — of the pain, not just the image of its terrible creation, being “shared” — endures. When the pseudonymous critic Uncas Blythe describes the Jackass players as “voodoo medics” for post-9/11 American society, he takes pains to underscore the fact that their continued dedication to their practice, bearing pain in perpetuity, is the locus of their power: “The triumph is in density,” he says. “There is something uniquely bonding and yet strikingly odd about repeatedly watching the same people suffer humiliation, pain, fear and revulsion again and again… Everyone, actor and spectator alike, is bound in an inescapable ritual.”

Devoting one’s life to agony in order to facilitate the exorcism of the dark and restless spirit of the age seems, prima facie, like the kind of thing only a madman or a saint would choose to do.

Which as You Know Means Violence is published by Repeater Books on 13 September.

Taken from the October/November 2022 issue of Rolling Stone UK. Buy it online now.